EVERETT — When John Wightman woke up from emergency spinal cord surgery last November, he couldn’t move his arms or legs. He breathed through a tube.

About a week earlier, Wightman’s daughter had found him collapsed and hallucinating on the floor of his Marysville home. Kristen Velez carried her 64-year-old father to the car and drove him to Providence Regional Medical Center Everett.

At first, doctors blamed a kidney infection. Then it was a blood infection and sepsis. Specialists found severe arthritis and an infected spinal cord. Doctors also mentioned signs of a stroke.

“We still don’t really know what happened,” Velez said.

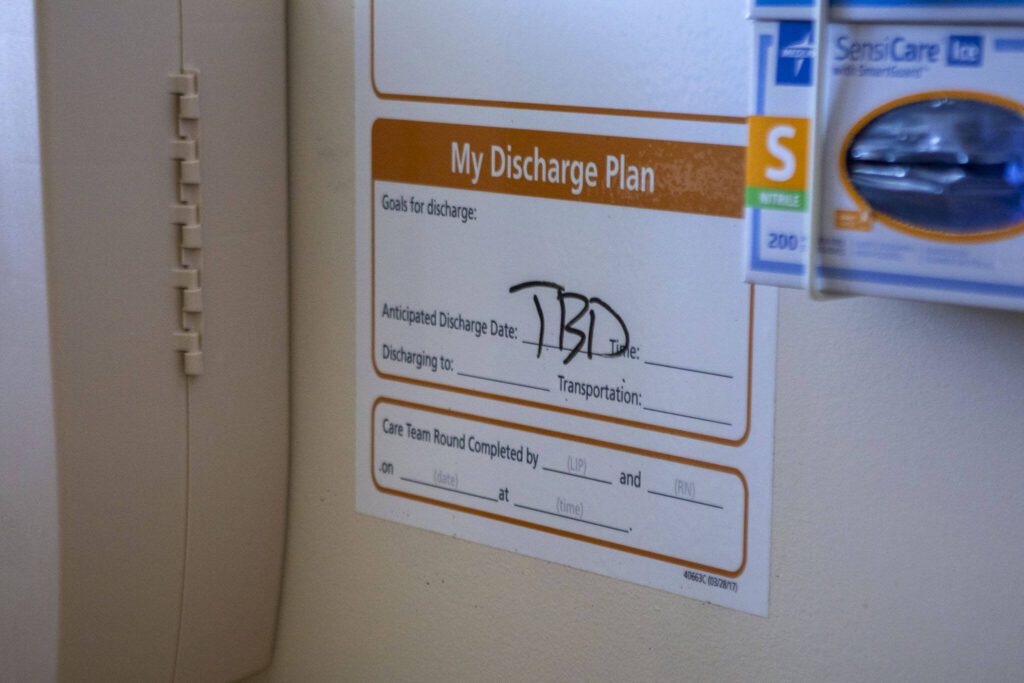

By Dec. 13, doctors said Wightman was medically stable and could transfer to a skilled nursing facility. With enough rehabilitation, he may be able to feed himself, or even walk again.

Providence case workers submitted Wightman’s application to every rehab facility in the state. None would take him. And he couldn’t leave the hospital on his own.

So, more than four months later, Wightman still laid in a hospital bed.

“I’ve been here a long time,” he said in April.

Most patients stay at the hospital for a few hours, maybe a few days. Some, like Wightman, have long-term needs the hospital must address through discharge planning before they can leave. Lack of insurance or citizenship documents, as well as other complex care needs, can slow the process. Those who need to transfer to another facility often face long waitlists and high barriers.

On any given day at the Everett hospital, up to 100 people are in Wightman’s situation: stuck in the hospital for months, or even years. Meanwhile, a state program meant to help is behind schedule.

‘So completely stressful’

After surgery, Wightman depended on a breathing tube for weeks. He couldn’t get out of bed, go to the bathroom or feed himself. But nurses were often too busy to come when he pushed the call button, he said.

“Someone in his condition who can’t scratch his own nose, it’s not enough for someone to check on him every couple of hours,” Velez said.

Providence Everett has one of the busiest emergency departments in the state. The hospital’s 600 beds are often full, or some are unavailable because of a nurse staffing crisis. Most hospital staff are trained to provide urgent care, but don’t have the skills or time to care for patients with long-term needs.

Some days, Wightman resorted to yelling for help. And when nurses did come, he felt like a burden.

“When you have someone shoving food in your face and not saying a word,” he said, breaking down in tears, “it’s really hard.”

Wightman’s family brushed his teeth, trimmed his hair and clipped his toenails. Nurses gave him sponge baths a couple times a week.

“From what I’m aware, that man hasn’t had a real shower in four months,” said Jojo Lynch, Velez’s mother. “If it weren’t for us coming in and taking care of him, I don’t even know what kind of shape he would be in.”

Lynch flew up from her home in Arizona several times to help Wightman and the rest of the family.

“It’s not only a toll on the patient,” she said. “It’s so completely stressful for the families.”

Since the hospital is overflowing, staff are constantly moving patients from room to room across multiple floors so they can fit new check-ins. Hospital staff moved Wightman at least nine times.

“Time and time again, I’ve walked into an empty hospital room that’s been cleaned and thought that my father died that day,” Velez said.

Wightman’s family could scout rehab facilities and talk with hospital staff, but the rest was up to Providence. And each time Wightman found himself in a new room, a new worker took on his case.

The hospital has about 20 case managers each working with 20 to 32 patients at a time, said Catherine Ambrose, senior director of care management at Providence Everett and Swedish Edmonds. The sixth and seventh floors in the A wing are reserved for long-stay patients, like Wightman. Workers there have heavier caseloads and visit patients once or twice a week.

“Patients and families coming from higher acuity settings may notice a shift in type of services they receive compared to what they had become accustomed to,” Providence said in a statement.

Velez said she wouldn’t hear from case workers for days or weeks, despite multiple phone calls and voicemails.

“When you meet the social workers, they come across as very nice,” Lynch said. “But after that, forget it. You’re left in the dark, unless you scream.”

The hospital’s care management team is in constant communication, Ambrose said, but she noted those conversations don’t always include patients and their families. Caseworkers are supposed to provide daily written updates for each case for the next worker who takes over. But Ambrose acknowledged there could be “gaps in handoff.”

‘What on Earth is happening here?’

An ever-changing room, care team and meal schedule made it almost impossible for Wightman to hold onto a sense of normalcy. And cracks in Wightman’s care made the family question his safety.

Once, Velez filed a safety complaint after walking into a new room on the sixth floor in the hospital’s A wing.

“Imagine a dungeon. Wet, dark, nasty,” she said. “I literally lost it when I went in there.”

At the time, a nurse was feeding Wightman a hamburger and a drink with a straw, Velez said. Doctors had him on a no-straw, soft-chew diet to prevent silent aspiration or pneumonia. In this room, Wightman no longer had a soft-touch call button that was compatible with his mobility, Velez said, or a lift to get out of bed for physical therapy.

“I immediately asked to talk to the charge nurse and expressed my concerns,” she said. “I was like, ‘What on Earth is happening here?’”

Velez said the charge nurse on duty dismissed her complaints.

The next time Velez visited her father, she videotaped on her phone so she would have proof of any more safety concerns. Velez said two nurses ran into the room and “demanded” she give them her phone.

“They tried to call me and my dad a liar,” Velez said. “Security was in my face threatening to arrest me, threatening to kick me off of the premises and never be able to come back.”

The hospital “promptly addressed” Velez’ complaints and moved Wightman to a different room, Providence spokesperson Erika Hermanson wrote in a statement.

“When Mr. Wightman’s daughter was observed video recording in his semi-private room — which he shared with another patient under our care — our caregivers, with the support of our security team, reviewed our recording policy with the patient and his family and respectfully asked that any photos or videos where the privacy of our patients or our caregivers was a concern be deleted,” Hermanson said on behalf of the hospital.

‘He could get better’

Velez visited her father nearly every day to help him leave the hospital. She scrambled to find an insurance plan after hospital staff said Wightman wasn’t eligible for state insurance. She had trouble navigating the market on her own, and landed on a plan that most facilities reject because of its low reimbursement rates.

Having state insurance helps, said Ambrose, care management director at Providence. But long-term care and rehab facilities still have limited spots. They’re often privately owned and have set quotas based on patient needs, insurance plans and gender. They also can be picky based on a patient’s care needs, including mobility and behavioral health.

“A facility may have a bed open,” Ambrose said, “but when we check, it’s a ‘female’ bed instead of a ‘male’ bed.”

These facilities are often as full as hospitals, facing severe financial strain and staff turnover. Long-term care workers are among the lowest-paid in health care, according to LeadingAge Washington.

But state insurance rates are still behind labor costs, said Lauri St. Ours, spokesperson for the Washington Health Care Association, in an email. Care worker licensing and credential centers are also seeing “tremendous backlogs,” she said.

Since December 2019, long-term care facilities in Washington have had to close thousands of beds.

“The unfortunate reality is that when mandatory staffing levels cannot be met, access declines,” St. Ours wrote.

At Providence, Wightman had about 45 minutes of physical therapy three times a week.

“That’s the only time he gets out of his bed,” Lynch said. “They found a wheelchair that he can use with his limited mobility, an electric one. They let him use it one time. And then they said they were going to order us one under insurance. But then they came back and said they couldn’t order it until he’s discharged.”

The family fought to keep Wightman in the hospital’s D wing, where they said he had access to a lift to get out of bed and into activity quicker. For someone like Wightman, every second of movement counts for long-term recovery and acceptance into a rehab facility.

“He’s showing progress, he could get better,” Velez said. “If he could even feed himself or take care of himself for a couple of hours at a time, that’s the difference from being able to go home or having to be in an adult home for the rest of his life.”

The hospital’s chart notes play a huge role in whether a facility will accept a patient. Wightman’s family believes misleading chart notes may have cost him a spot.

In one case, Wightman asked to be moved from an uncomfortable metal chair nurses provided as an alternative to his bed. Nurses then noted on his chart: “Patient refused physical therapy.” In another case, a physical therapist came into his room while he was waiting for a meal.

“It was either food or physical therapy,” Lynch said. “He chose food.”

Caseworkers submitted Wightman’s application to all 120 skilled nursing facilities in the state, Ambrose said. After weeks of waiting, all programs rejected him. The next step was re-referrals.

Last year, Providence partnered with skilled nursing facility Bethany of the Northwest to staff 60 beds on the hospital’s Pacific campus. Hospital staff assured the family that Wightman would be transferred to the program, Lynch said.

But a month went by, and he was denied. Ambrose said the facility requires at least three hours of physical therapy a day, and it could be too much for Wightman.

“He was looking so forward to it,” Lynch said. “Emotionally, that man has been through a roller coaster.”

‘The system is broke’

Last year, the state allocated over $500 million to help patients like Wightman. Some of the money went toward a new patient discharge task force and a two-year pilot program at Providence Everett and four other hospitals.

The goal of the program, based on a model at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, is to collect data and determine the need for new legislation and state-funded care services. Harborview’s bed readiness program designates some hospital beds and staff to focus solely on patients with discharge barriers.

But the money runs out next June, and the task force has yet to launch the program. It’s been a lot of back and forth with hospitals and state agencies, Ambrose said, but they’re in the final stages of a contract. The program should kick off in the next few months, she said.

“The ultimate problem is, there’s not enough places for folks to go,” said state Sen. June Robinson, of Everett, who co-chairs the Senate Health & Long Term Care Committee. “We’ve tried to address the issue, but it never seems like it’s enough.”

In 2022, the state invested over $91 million in nursing assistant certification sites, discharge planning progams and long-term care facilities. Since then, some hospitals have seen up to 100 more discharges per month, according to the state.

The state also raised insurance reimbursement rates for long-term care facilities, behavioral health providers and hospitals. Lawmakers predicted a $1 billion revenue jump to help with labor and care costs.

Robinson isn’t sure the money is having a significant impact. And issues surrounding patient discharge didn’t get much attention in this year’s legislative session, she added.

In the meantime, Ambrose said families can scout facilities for their loved ones with an online Medicare comparison tool. Facility workers could also visit patients while reviewing their application.

“This could be anyone’s family member,” Velez said. “Not only do we have someone sitting in a hospital who we’re watching waste away, we can’t figure out how to transition them. And we’re not having any resources or help.”

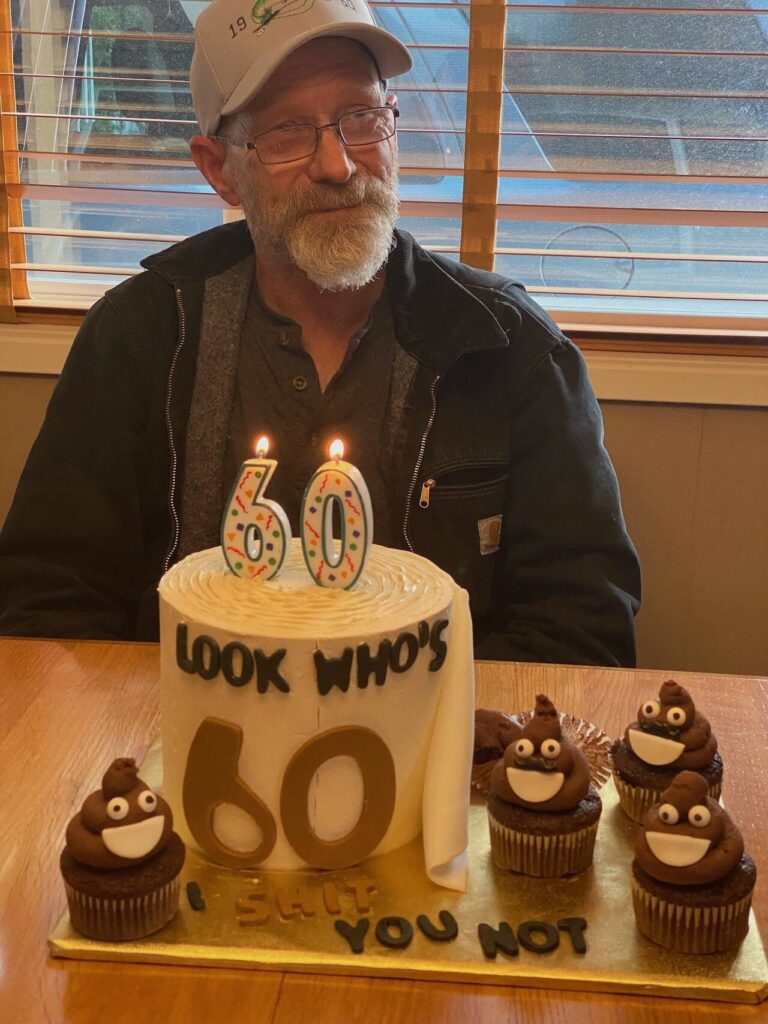

On April 24, nearly five months after Wightman arrived at Providence, the hospital discharged him. He’s now at Everett Transitional Care Services, a care home on Providence’s Pacific Campus where his application previously had been denied. His daughter credits the outcome to a Daily Herald reporter’s visit with Wightman and hospital leaders. And because his hospital stay reduced his income, Wightman now qualifies for state insurance.

“We haven’t done everything perfectly,” Ambrose said, misty-eyed. “I’m somebody’s daughter. I hear them.”

A longtime fisherman, Wightman yearned for independence and the outdoors as he waited for months in his hospital bed. When he was lucky, on a clear day, he caught glimpses of Puget Sound from a seventh-floor window.

“The system is broke,” he said through tears. “We need to fix it.”

Sydney Jackson: 425-339-3430; sydney.jackson@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @_sydneyajackson.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.