By Aishvarya Kavi / © 2024 The New York Times Company

WASHINGTON — Nearly 1,000 American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children, including 60 from the Pacific Northwest, died while attending boarding schools set up by the U.S. government for the purpose of erasing their tribal ties and cultural practices, according to a report released Tuesday by the Interior Department.

“For the first time in the history of the country, the U.S. government is accounting for its role in operating Indian boarding schools to forcibly assimilate Indian children, and working to set us on a path to heal from the wounds inflicted by those schools,” Bryan Newland, the department’s assistant secretary for Indian affairs, wrote this month in a letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland that was included in the report.

The report calls on the federal government to apologize and “chart a road to healing.” Its recommendations include creating a national memorial to commemorate the children’s deaths and educate the public; investing in research and helping Native communities heal from intergenerational stress and trauma; and revitalizing Native languages.

From the early 1800s to the late 1960s, the U.S. government removed Native children from their families and homes and sent them to boarding schools, where they were forcibly assimilated.

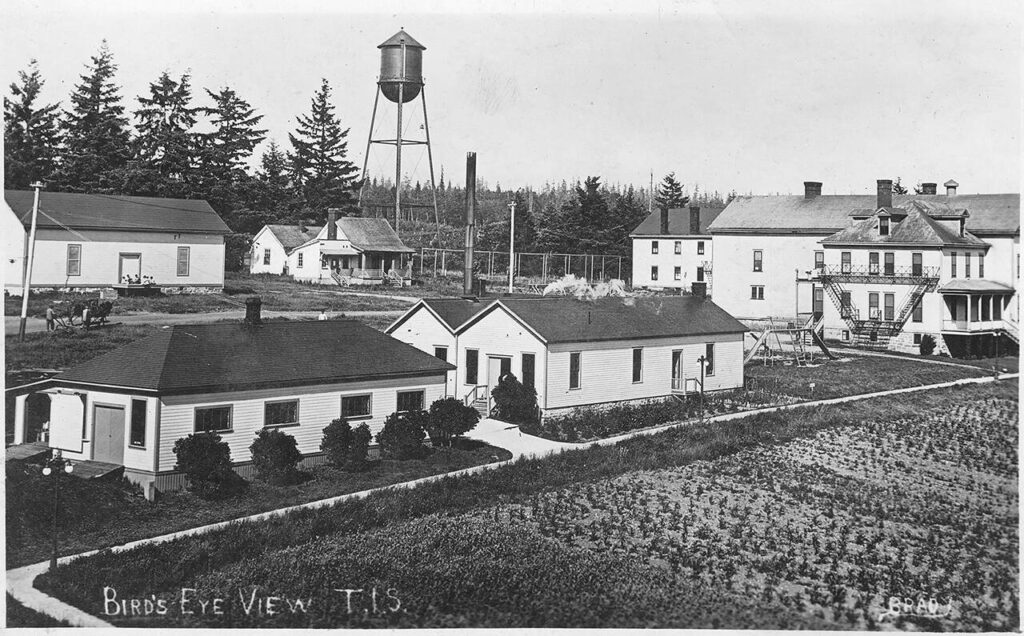

It spent nearly $25 billion in today’s dollars on the comprehensive effort, according to the investigative report released Tuesday, including operating 417 schools across 37 states and territories where children were physically and sexually abused. They were also forcibly converted to Christianity and punished for speaking their Native languages. From 1857 to 1932, thousands of children passed through one of those schools on the Tulalip Reservation.

The report identified by name almost 19,000 children who attended a federal school between 1819 and 1969, though the Interior Department acknowledges there were more.

The accounting of the bodies of Native American children was one of the main goals of a federal initiative begun more than three years ago after Canada discovered the remains of 215 children at the site of a defunct boarding school and announced a similar effort. Haaland, a Laguna Pueblo citizen and the first Native American Cabinet secretary, has led the effort in the United States.

Tuesday’s report, the second and final from the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, found that 973 children died at Indian boarding schools and were buried at 74 sites, 21 of which are unmarked. The Interior Department said it was working with tribes that want the remains repatriated.

Though political support eventually faded for the forced assimilation of children, the effects of the uprooting and abuse are still felt by Native communities, according to the report. Children were left with lasting psychological trauma, and studies funded by the National Institutes of Health have linked poor physical health in Native American adults to their attendance at federally run schools as children.

The department conducted interviews with hundreds of survivors as part of its investigation. Some described widespread sexual abuse at the schools, as well as routine physical abuse. One attendee described newcomers being stripped of their parkas, which were burned in a furnace. Another recalled that many children became “violently ill” from highly processed foods like powdered milk and canned meats, and were then beaten for soiling their bedding or clothing.

“I remember my braids being cut off; washed like we were dirty; talked to us like we were dirty,” one unnamed participant, from South Dakota, said in the report. “We were dressed in uniforms.”

Others described lasting feelings of abandonment and shame from having their family connections severed when they were taken away to attend the schools.

“I think the worst part of it was at night, listening to all the other children crying themselves to sleep, crying for their parents and just wanting to go home,” said another unnamed participant, from Michigan.

A participant from Washington described how her sister, now a grandmother, still could not sleep in the dark and would wake up screaming when the light was turned off because she had been routinely locked in a closet as a young girl.

The report said that aside from experiencing lasting physical and psychological effects, many children learned only agricultural or manual and domestic labor skills, with tribal economies destabilized by their lack of formal education.

The report said that although “a change in our nation’s understanding” had come quickly — with the troubling history of Indian boarding schools now discussed in books, television shows and movies — many communities were far from healed.

“The new report provides critical information that is needed to understand the complete history and impact of the federal Indian boarding school era,” Beth Wright, a lawyer with the Native American Rights Fund who worked on boarding school cases, said in a statement. “The next step is for the Department of Interior to provide resources and funding directly to tribal nations who desire to research, address and tell their own stories of the impact the federal Indian boarding school era has had on their own communities and people.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Information from The Daily Herald archives was included in this report.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.