EVERETT — As a teacher at Cedar Wood Elementary 20 years ago, Theresa Kemp had a pretty sweet setup: bright motivated students and an eager army of parent volunteers.

She could have stayed at the Mill Creek campus and been perfectly content. Instead, she felt drawn to a school with challenging demographics led by a first-year principal who quickly built a reputation for high standards and a tireless work ethic.

Kemp joined the staff at Madison Elementary to work for Joyce Stewart. The Everett campus was getting noticed inside and outside the district for state test scores that defied socioeconomic expectations. Stewart had a way of coaching teachers, spending time in their classrooms and going over student papers to offer suggestions. Her determination rubbed off on others. They didn’t want to let her down and they knew she’d never ask them to do anything that she wouldn’t do herself.

The Madison story was about more than test scores. Stewart emphasized the arts and community. She paid for groceries, utilities and car repairs for families in need and deflected personal recognition.

When Stewart was transferred to Evergreen Middle School, Kemp followed. So did the academic turnaround that had happened at Madison, but on a bigger campus with older kids.

Stewart later was recruited to the district office where she became deputy superintendent. Instead of one school, she’d oversee 11 directly and have input in all 26. Over 10 years, Everett’s graduation rose from 82 percent to 96 percent, and Stewart played an important role.

This fall, Stewart won’t be around. She retires Wednesday.

“She will be missed in so many ways, by staff, students and the district,” wrote kindergarten teacher Beth Ristig and literacy coach Sherri Grinage who were part of Stewart’s original Madison staff.

“She is a just a legend in our district,” said Dave Peters, Henry M. Jackson High School’s principal. “With her, you would think: Is this possible?”

As an administrator, Stewart never really left the front lines. Much of her work day was spent on campus; much of her time after school was spent catching up at district headquarters, often until 9 p.m.

Even as deputy superintendent in a district with enrollment approaching 20,000, she made connections with individual students, especially those facing barriers, and worked closely with staff who shared the same desire to see them succeed.

Such was the case when Stewart, Kemp, and others hatched a plan to make sure one more student was part of the Class of 2017. If he were to graduate the same year as his peers, he would need to do so before fall term began. And that was the next day.

They tracked him to the address of a friend where he’d been living, knocked and called his name.

They peered through a window, spotting someone on a couch, most likely sleeping, but possibly playing possum.

“This is Mrs. Kemp,” his former freshman English teacher called out. “And you have a lot of work ahead of you today.”

He was outnumbered.

He plugged away on a computer at Evergreen Middle School for nearly 11 hours. By nightfall, he finished the online history course, earning that elusive final credit.

They had a graduation gown waiting for him as well as cake, and cranked up “Pomp and Circumstance” while snapping photos.

It was around 9 p.m. Kemp was at home preparing for the first day of school the next morning. Stewart called with the news.

The teacher who’d followed her to Madison, Evergreen and to a student’s front door was delighted but hardly surprised.

“That was just so Dr. Stewart: What does it take to get every kid through?”

Kelly Shepherd, principal at Sequoia High School, was there, too. She knew Stewart had a knack for finding young people who didn’t want to be found and bringing them back into the fold.

“There were many a day I would drive out to a home with Joyce Stewart,” she said.

Making the rounds

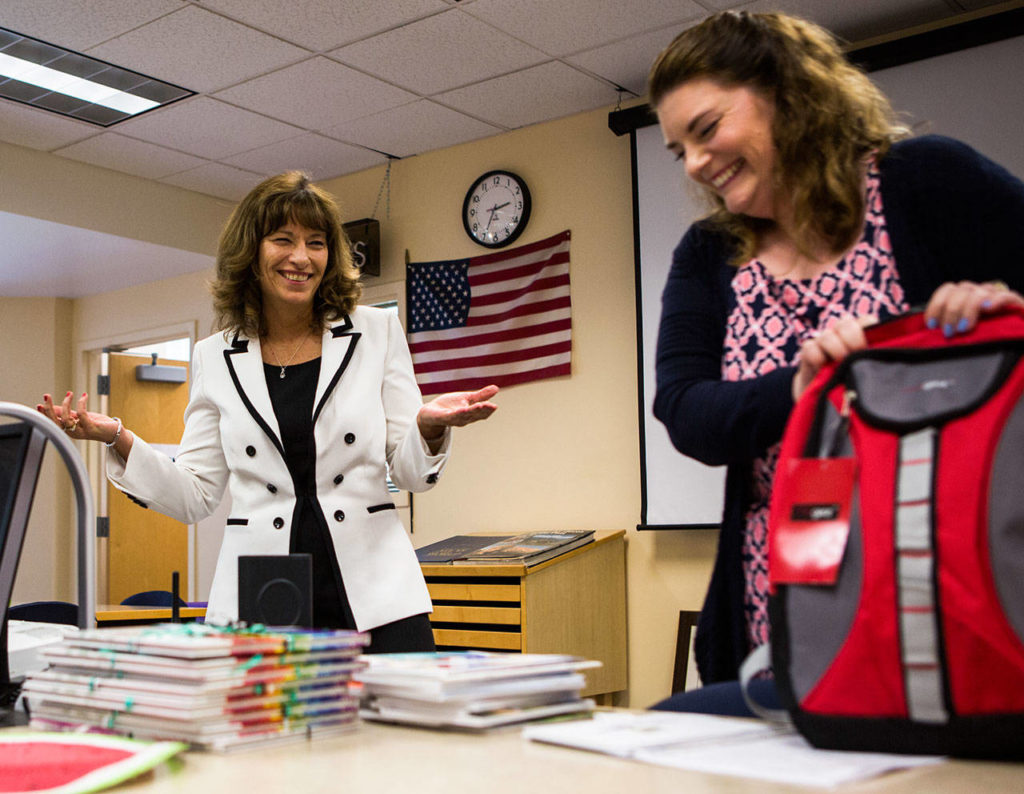

In the final days before classes let out for the summer, Stewart made her rounds from school to school.

The district’s second in command knew everyone by name: teachers, cooks, parents, classroom assistants.

At Lowell Elementary, she dropped a coffee off for the office manager of more than 40 years. She stopped by the classroom of a retiring special education teacher and she was mobbed by well wishers.

The main reason for her visit was to check on a boy who’d been bullied at his former school. Stewart orchestrated his transfer and he was thriving in his new surroundings under a teacher she’d handpicked. Stewart told the boy that she is proud of him. She called his mom to tell her how well he was doing and ask her to make him tacos, his favorite, for dinner.

Before she left Lowell, someone mentioned that 15 students didn’t get yearbooks, presumably because of financial hardship. Stewart said she’d take care of it, and did.

At Everett High School she caught up with Amina Hussein, a student born in a Kenyan refugee camp who is the incoming ASB vice president. Stewart paid a deposit to get her into a program to learn about opportunities at black universities she hopes to attend.

At Hawthorne, the reception was similar.

Kindergarten teacher Judi Caudle said word of Stewart’s tenacity and ridiculously long hours preceded her arrival as deputy superintendent. Teachers elsewhere knew what happened at Madison and Evergreen and wondered if they’d measure up. What Caudle discovered in Stewart was someone who led by example, not by authority.

“Whatever it takes, that was her model,” Caudle said.

In between school visits, Stewart popped in unannounced at City Hall. She had ideas to share.

In the lobby, she bumped into a middle-aged man who greeted her warmly.

His son struggled with mental health issues, even by middle school. At Evergreen, she’d worked with him and his family. His struggles continue, but the father is still grateful and told her so.

Lessons learned

Stewart grew up on a farm in Belfield, North Dakota, pop. 950 these days. She was the fourth of 11 children. Her parents, 94 and 86, still live on the farm where there was always more work to do.

She went to college in Montana to become a teacher and worked at public and private schools in three states. Two years ago, Stewart received the Robert J. Handy Most Effective Administrator Award as the state’s outstanding public-school administrator for large school districts. Last month, her sister, Janel Keating Hambly, superintendent of the White River School District, was given the same honor. The sisters have talked teaching strategies with one another for more than three decades.

Yet when Stewart was hired at Madison, she had no administrative experience, not even as an assistant principal.

She knew the school district took a risk on her and was determined to make sure they’d have no regrets.

After her 12 years as a principal, Superintendent Gary Cohn offered a promotion. “I found her to be an outstanding principal, outstanding leader, outstanding community organizer, somebody who I immediately could see had an exceptional command of instruction, assessment and curriculum, which is an absolutely critical,” Cohn said.

The way Cohn saw it, there are no great schools without great principals. By losing one, he could gain many more if she trained them.

While graduation rates improved, Stewart would think about the disaffected students lost along the way. She refused to call them dropouts because that would seem like she’d given up. She got some back, but she learned what strategy might work with one student might not work with another.

Last summer, Stewart met up with a videographer and took to the streets to talk to the homeless over several nights. She wanted to hear their stories, to try to understand addiction and what went wrong.

What, she wondered, can we learn from them? Last fall, she played the video to groups of teachers, administrators and classified staff. Some of the faces looked familiar, like the young man in the dirty clothes with the dog by his side. They were hearing the voices of former students from elementary, middle and high school — the kids who disappeared.

Some people cried.

The message Stewart hopes staff took away from it was this: “Our kids need us, each one of us. Sometimes all it takes is one trusted adult and we all need to work on that in our schools.”

So difficult … so gratifying

As June slipped into July and schools sat empty, Stewart paid a last visit to Madison where the library is named after her.

It was nice to have the campus to herself, to ponder how fleeting time really is.

From there, she drove to Evergreen where she gave the principal words of encouragement.

The truth is, she hadn’t wanted to leave Madison and cried at the news 17 years ago.

“In the end, that was the greatest thing that ever happened to me in my career,” she said. “It was so difficult. That’s what made it so gratifying because it was so difficult.”

The joy was in the challenge and that made for a lot of joy.

She spent countless hours after school, often on Friday evenings and Saturday with students who needed to catch up or someone to talk with.

It was also during her time at Evergreen she went from nurturing to nurtured. Her staff supported her after her 42-year-old brother died of a heart attack, after she was diagnosed with breast cancer and after her husband was given three to five years to live. He’d been diagnosed with Pick’s disease, a kind of dementia similar to Alzheimer’s though far less common.

“When you love what you are doing, and you are surrounded by people and it’s a field of hope, that’s what got me through it,” she said.

That, and her family, including her daughters, both adopted from Korea, who are now in their 30s.

When Ali Dacones was a sixth-grader at Evergreen, she would watch Stewart. She was always out in the halls, always getting to know students and always insisting they walk in a straight single file line to the cafeteria. When Dacones earned her master’s degree from Western Washington University earlier this year, Stewart attended her graduation in Bellingham. She’d always told Dacones, a 2015 Cascade High School graduate, she’d make a good teacher some day.

Dacones will return to Evergreen Middle School this fall to teach English.

Stewart will not be there. And yet, in some ways, she will. “I feel like I always have her in the back of my head, striving to be my best,” Dacones said. “And I know she’s only a phone call away.”

Eric Stevick: 425-339-3446; stevick@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.