SULTAN — As far as salmon habitat goes, the Sultan River is a prime spot for thousands of juvenile fish that swim toward Puget Sound the first several months of the year.

At Culmback Dam, the Snohomish County PUD regulates water temperatures to ensure fish can thrive in their preferred cold environment. And if needed, the PUD can release more water from Spada Lake to mimic a natural river’s flow.

Even still, Chinook salmon numbers are down this year — not only in the Sultan where anglers can’t fish for salmon, but across Western Washington. Last month, the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, along with local tribes, announced plans to close several popular salmon fishing areas this year to prevent anglers from accidentally killing Chinook.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s fisheries service still needs to review the decision. And state fishery managers will offer another round of public comment later this month before Fish and Wildlife confirms its annual fishing regulations in June.

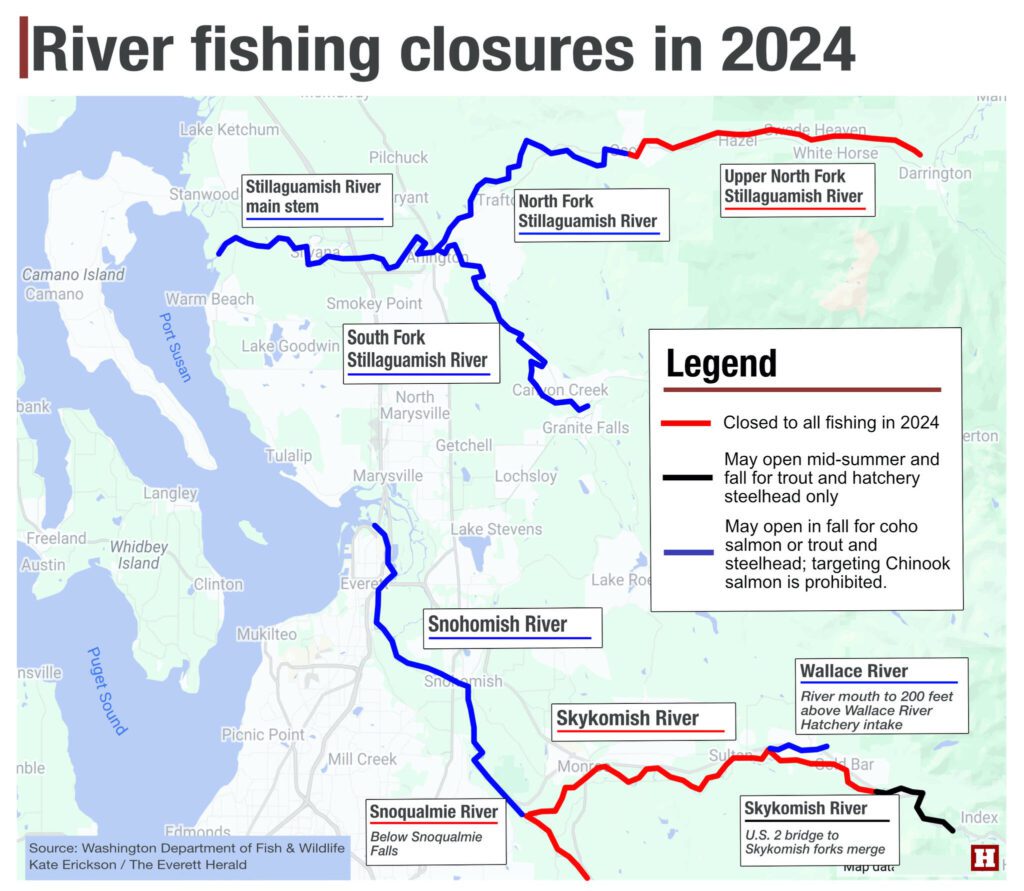

But as of this month, Fish and Wildlife proposes closing the north fork of the Stillaguamish River to salmon fishing from Sept. 16 to Oct. 31. The agency plans to close the Skykomish and Snoqualmie rivers for salmon fishing from May 15, 2024 until May 14, 2025.

This fall, anglers can fish for salmon on the Wallace River and portions of the Stillaguamish and Snohomish rivers, with a catch limit of two cohos and no wild Chinook or chum.

State Fish and Wildlife expects to publish emergency fishing rule changes during the summer and fall, spokesperson Chase Gunnell said.

Co-managers of local fisheries find about 10% of fish die after anglers hook and release them.

“There’s a relatively small chance of them hooking a Chinook,” said state Fish and Wildlife biologist Pete Verhey. “But there’s a chance, and so basically, we’re in a spot now where we can’t even afford that chance.”

On a Monday morning at Sportsman Park, three fish biologists with the PUD stood by the Sultan River with notebooks and pens on hand. One of the PUD’s smolt traps floated several feet away in the center of the river, held stationary by ropes tied to nearby trees.

The trap looked like a raft with a 5-foot diameter cone in the middle. The cone was constantly rotating and funneling fish into a well filled with water.

After 17 hours of fishing, the biologists were ready to start counting.

Andrew McDonnell reeled in the trap so it was flush with the shore, then boarded the raft. From there, he and Kyle Legare took turns dipping their nets into the well to catch all of the fish — a process that can take anywhere from 45 minutes to several hours, depending on the number of fish in the trap.

With every scoop, they called out the number of fish, their species and an estimate of their age.

The trap caught 952 fish during the 17-hour session: 677 pink salmon, 217 coho, 46 Chinook, 6 chum, 5 steelhead, and, one surprise lamprey.

Biologists with the PUD usually keep the trap in the water from January until June.

Last year, the trap caught 647,106 Chinook. This year, biologists deployed the trap a month earlier than usual. So far, they’ve counted about 2,364 Chinook.

Biologists with the PUD are only required to monitor salmon numbers for two years out of a six-year period, through its federal license. But the biologists tend to still put the trap out every year to provide data to fishery co-managers.

This year, PUD’s biologists aren’t required to monitor, so they haven’t opened the trap every week. And when it is open, the trap catches an estimated 3% of the fish in the river, McDonnell said.

He said Chinook numbers aren’t as high as they have been historically.

“There’s no smoking gun,” said McDonnell, about Chinook declines. “The habitat is here. We just need more fish.”

Warm temperatures, extreme weather events — like this year’s drought — and predation are some factors that can contribute to salmon declines.

Fish and Wildlife sets an “exploitation rate ceiling,” or the number of fish that can be killed in state-managed waters without harming their recovery, said Verhey, the Fish and Wildlife biologist.

This year, that number is 106 wild adult equivalent Chinook in the Snohomish basin, because biologists predict adult Chinook return numbers to be low.

Since 2022, Fish and Wildlife has had to start restricting both marine and freshwater fisheries due to low returns of wild Chinook, Verhey said.

“There’s not too many river fisheries where you can go and catch these big ocean-type Chinook salmon and take them home,” he said. “And so it’s a big deal.”

Cary Hofmann has worked for CNH Guide Service for 13 years, taking anglers out to local rivers and Puget Sound to fish for salmon and steelhead.

“I used to fish nine months out of the year,” he said. “Now it’s only two.”

Over the past five years, as Chinook runs started underperforming, the fishing scene has changed dramatically, Hofmann said.

He used to take anglers to fisheries 15 minutes from his home in Woodinville. Now, more guides like him are taking customers to saltwater fishing areas, stretching his commute to one or two hours.

“It’s far from ideal,” he said, “but the fish need it.”

Ta’Leah Van Sistine: 425-339-3460; taleah.vansistine@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @TaLeahRoseV.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.