BARING — In his 28 years of life, Casey Myers had never been in trouble like this.

In 2004, he was 2,464 miles into the Pacific Crest Trail. Mice had eaten most of his food. And through torrential rain, Myers was checking over his shoulder for the mountain lion that seemed to be “contemplating whether I was worth eating.”

He finally reached U.S. 2 at Stevens Pass. He stuck out his thumb.

“I was shivering so bad that I was worried I was gonna stop shivering. That’s when you know you’re really in trouble,” Myers told The Daily Herald this week.

“And then there comes Jerry.”

Jerry Dinsmore pulled to the side of the road in his pickup with vanity plate “PCT DAD.”

He offered Myers a ride, just like he helped hundreds of PCT hikers every season with his wife, Andrea Burr-Dinsmore, whose license plate read “PCT MOM.”

Myers recouped in their living room for a few days, then went back out to finish the trail.

“I can picture them, I can picture how I felt around them,” he said. “I mean, they let me into their house. There’s nothing more trusting than that.”

The PCT community has since lost both “trail angels.” Andrea died of pancreatic cancer in 2017. She was 68.

Jerry, who lived with health issues for years, died this month. He was 81.

‘Where’s he finding these people?’

Nestled in dense forest in the shadow of the Cascades, the Dinsmore Hiker Haven welcomed thousands of PCT hikers to Baring over 20 years.

They came from around the globe. A 23½-mile hitchhike west of the pass led to a meal, a bunk and important advice before venturing into the home stretch. It’s another 190 miles to Canada, and the North Cascades are “nothing to joke about,” PCT hiker Steve Cain said.

This week, Jerry’s daughter, Diane Altman Jennings, returned to the haven, to dig through years of thru-hiking artifacts. It looks like a barn behind the Dinsmores’ modest single-story home. Her rubber work gloves glistened in the sun as she gestured to the two-acre lawn covered in deep snow.

“When the snow melts, we’re not totally sure what we’ll find here,” she said.

The inside of the haven offers a hint.

There’s a dirt-covered wedding dress hanging from the rafters. Two guitars and a set of bongos. A mounted stag with a sombrero. Foreign flags. A string of bandanas from each “class” of PCT hikers. A rubber chicken used as a kind of bat signal on the trail — if it was up along U.S. 2, it meant there was an empty bunk at the Dinsmores’.

The property was quiet last week, missing the gaggles of exhausted-yet-eager backpackers. They would tell tall tales around the campfire, dressed in the haven’s spare onesies and prom dresses as they waited for their trail clothes to dry.

“They got weird with it,” Jennings said. “But they had fun. Stories are their legacy, honestly.”

It started in 2002. Jerry, a career truck driver and diesel mechanic, didn’t know much about the famous hike that runs up the West Coast and through town. He just knew the stranger on the side of the road looked like he needed help.

Thru-hikers often do, Jennings said.

“They come off the trail emaciated and really looking rough,” she said.

Jennings stood between twin-sized bunk beds, where past visitors treated black toe and other painful trail ailments.

When the Dinsmores began taking in hikers, they would show up to family dinners with a posse of strangers.

“At first it was a little bit puzzling,” Jennings said. “Like, where’s he finding these people?”

It quickly snowballed. In 2017, the Dinsmores were declared “Trail Angels of the Year,” partly for their work tracking late-season hikers who ventured into dangerous conditions.

They made hikers promise to call the haven when they reached civilization. No call, and the Dinsmores would trigger search and rescue.

“That’s how Andrea saved lives. I’m dead serious,” said Cain, the Indiana-born hiker known on by his trail name “Hoosierdaddy.”

In 2014, the Red Cross honored the Dinsmores as “real heroes” when they called in a rescue for a man who left the haven and got stuck in a snowstorm with just a package of ramen noodles and some mashed potatoes.

The North Cascades are nothing to mess with, said Carolyn “Ravensong” Burkhart, thought to be the first woman to solo thru-hike the entire PCT in 1976. The Dinsmores inspired Burkhart to open her own hiker haven in Mazama to help travelers through the treacherous peaks.

“There’s fewer of us (havens) up north,” she said. “It’s the Dinsmores and myself.”

Hikers often knew of the Dinsmores before meeting them. That was the case for Liz Sexauer “Reststep” Fallin, who had cut through miles of wildfire smoke in 2015 before showing up at their doorstep. The PCT is so tough, she said, that something as simple as carrots from a stranger is deemed “trail magic.”

So a mattress, a burger and a host with insight on the upcoming trek?

“That’s a big deal,” Fallin said.

‘The great equalizer’

The Dinsmores collected so many stories about the PCT, they may as well have hiked it themselves.

“(Jerry) always said you could have doctors and lawyers and construction workers and people just starting out,” Jennings said. “This was the great equalizer.”

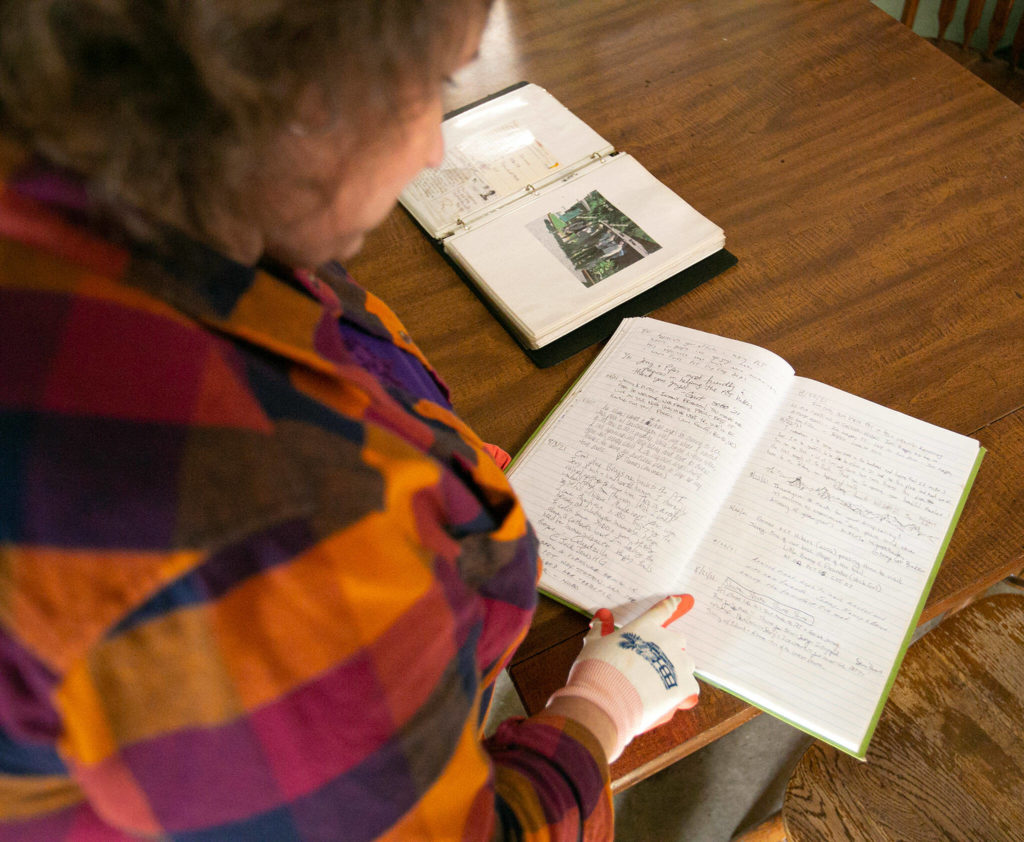

The Dinsmores’ guestbook confirms that.

Inside, newbies and veterans with trail names like “Mary Poppins,” “The Boston Scrambler” and “Slingshot” celebrate new friends and lament sore toes. A hiker from Germany describes feeling “new born” from his stay.

“I’ve traveled the globe for almost 10 years, and I have seen and met a lot of generous people,” a Swedish hiker wrote in 2017. “But this … this really blew my mind. You guys are angels, that’s for sure.”

A California man left a note in 2018 after he was struck by lightning.

Jennings remembered that group of hikers well.

“They said, ‘There is nothing on this trail that can stop us.’ And the next day he got struck by lightning,” Jennings said. “He had that darn tuna fish can in his jacket. And that’s what attracted the lightning.”

That shirt is still hanging in the haven. The bolt tore it to shreds.

In frantic scratchy letters, the man known by his trail name “Thor” wrote:

“I got struck by (expletive) lightning three days ago. I’m lucky to be alive and incredibly touched by this generosity. Much love forever.”

Andrea met Jerry, a mechanic, in the midst of her 30-year trucking career.

“He said, ‘I’ll keep it running if you go out with me,’” Jennings recalled. “The picture of my dad would be him leaning against a Kenworth, smoking a cigar and telling stories. The original mountain man.”

Around the campfire, Jerry would recount how his dachshund Bug chased off a bear. Or how he found and lugged an old caboose to the Iron Goat Trail. Or how he could tell time based on the whistles of the trains barrelling just a stone’s throw from the house.

To locals, he was the guy who kept the Skykomish school bus running. The boys basketball team gave him a special award. Not for being a coach or parent — just a No. 1 fan.

When Andrea got sick with cancer and was in bed in her final weeks, passing trains would blow an extra whistle for her.

The future of the haven is uncertain now. A sanctuary like this is expensive to run, and those with the time to do it are often retired. In the past few years, the haven in Baring relied on volunteers and donations from the trail community.

“He took care of the hikers. And then at the end, the hikers really took care of him,” Jennings said.

Some are carrying on the torch.

Myers, now an Oregon science teacher, started picking up thru-hikers that need help.

“Those guys saved our asses,” he said. “This is my way to pay it back.”

Cain, meanwhile, hiked the PCT with a vial of Andrea’s ashes.

“Because Andrea had never hiked the PCT, I was going to show her the PCT, show her how beautiful it is,” he said. “And she was going to show me what it is to be an angel.”

The trail angels’ generosity toward strangers helped him see the good in people.

“I retired from being a cop for 35 years and I really didn’t trust anybody. I’d seen the worst in humanity,” Cain said. “But you know what? People are good.”

Claudia Yaw: 425-339-3449; claudia.yaw@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @yawclaudia.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.