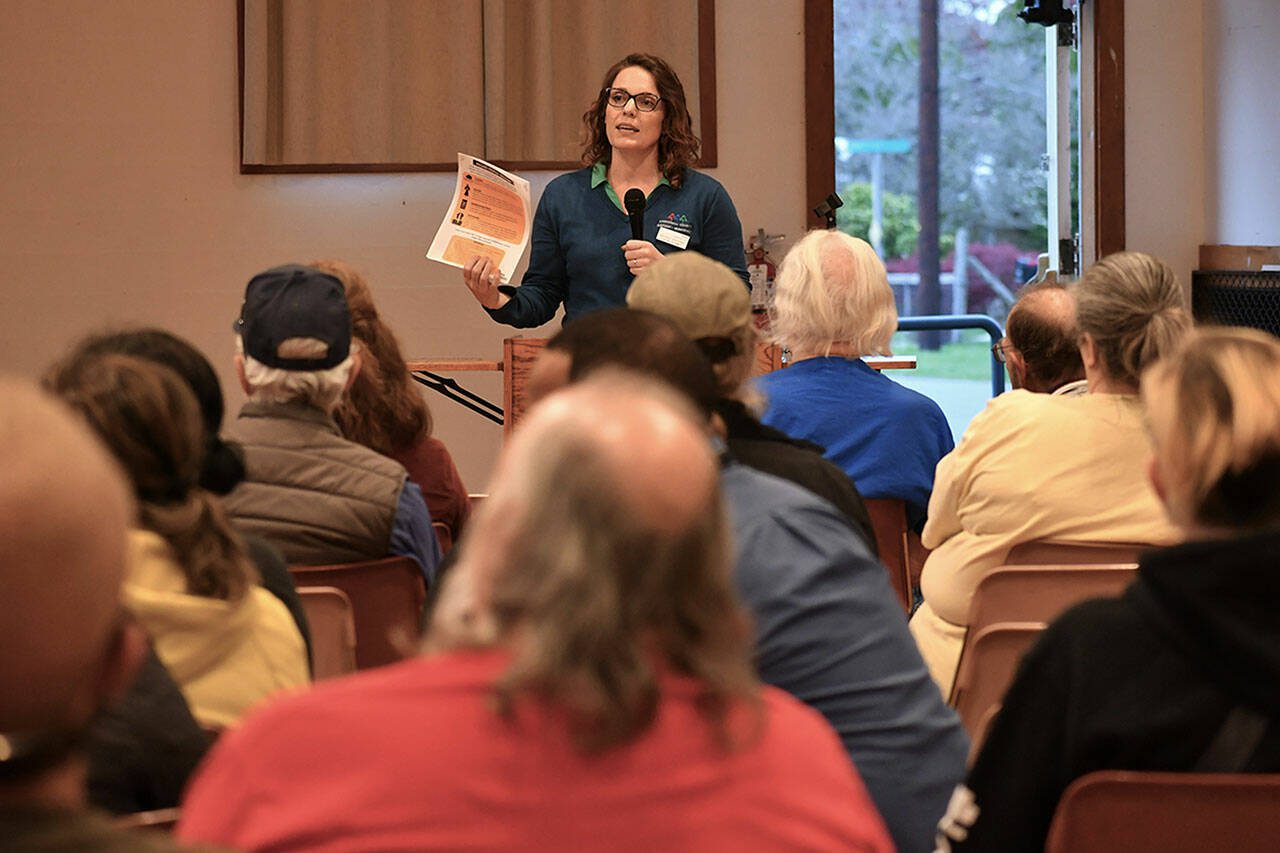

EVERETT — Four Western Washington counties, including Snohomish, are pushing a new evacuation messaging campaign to the public.

The goal, county officials said, is to simplify phrasing to save lives.

Called “Ready, Set, Go,” it provides three levels of action for the public. The messaging is new, while the levels are not.

“Historically, the fire service has used a level 1, 2, 3, and it aligns perfectly with ready, set, go,” Snohomish County Emergency Management Director Lucia Schmit said. “The only difference is that you kind of have to know what a Level 2 means and it’s not necessarily intuitive.”

These are the new levels:

• Ready (Level 1): There is a hazard in the area, be prepared and gather everything a person would need to evacuate.

• Set (Level 2): Be prepared for a sudden or short-term evacuation notice. Everything a person would need should be packed.

• Go (Level 3): Evacuate the area immediately.

When Schmit was a child, she was forced to evacuate her home in California on short notice due to the 1991 Oakland Firestorm. Also referred to as the Tunnel Fire, it killed 25 people and destroyed over 3,000 buildings. It moved fast. She wanted to bury some toys in the backyard in case her home burnt down. Her mom didn’t let her.

“My idea of essentials that needed to go in the car were different than hers,” Schmit said.

The three-stage evacuation plan announced Tuesday is designed to mirror what incident management teams use while fighting wildfires. The evacuation plan applies to all hazards, county officials said, but it’s mostly geared toward wildfires.

If you ever feel unsafe ahead of an evacuation warning, it is OK to leave. Snohomish County also has a website, Snoco.org/safety, with more information on evacuations and general emergency preparedness. It also includes a sign-up for emergency text alerts.

The new messaging from King, Thurston, Snohomish and Pierce counties comes as wildfire risk in Western Washington has increased due to climate change. Approximately 150,000 people in Snohomish County live in the Wildland Urban Interface, a term used to describe populated areas at higher risk of wildfires.

Eastern Washington is generally more susceptible to wildfires due to the simple fact that it’s normally dry during fire season. Meanwhile, some forests west of the Cascades have likely not burned for over 300 years.

Snohomish County and other areas west of the Cascades have not consistently had large wildfires more commonly associated with California, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico and Arizona. Those states have dealt with many big fires before, while it’s relatively new to a lot of people in Western Washington, Schmit said.

The Cascades and Olympics are typically wet mountain ranges.

That’s changing.

The explosive 14,000-acre Bolt Creek wildfire near Skykomish was a wakeup call in late summer 2022, as it threatened cities and communities along U.S. 2.

“The entire legacy of development in our area was built around forest fires not being a concern because we were traditionally moister,” Schmit said. “We didn’t have the invasive pests stressing the trees. We didn’t have these extended heat events that just carry the stress over from year to year. What we’re having to do is readjust our thinking.”

On Tuesday, there were a dozen large fires burning across Washington. Smaller fires in Snohomish County have already caused closures, including the 134-acre Huckleberry Flats Fire near Darrington and the 802-acre Dome Peak Fire burning in the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest near the Pacific Crest Trail. Suiattle River Road remained closed due to firefighting efforts.

Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest staff were also monitoring the 1,869-acre Airplane Lake fire a few miles east of the Snohomish County border, in Chelan County.

On Tuesday, Snohomish County also announced a complete outdoor fire ban. Propane-fed fire pits and enclosed barbecues that do not use wood are still allowed.

Deadly fires in Hawaii and Spokane have put wildfire evacuations in the spotlight. Escape routes play a key part in the tiered alert system. The county does not want everyone on a road at once, clogging traffic and making it hard for people to quickly get out of a hazard zone.

“We have communities up and down Highway 2, we have communities up and down Highway 530, where there’s one way in and one way out,” Schmit said. “We know it’s going to take a while to get everyone out of the valley. There might be a certain amount of people that will see those messages and say, ‘Well that seems silly, the fire is miles away.’ Fire moves quickly and gridlock doesn’t.”

Places can get cut off, too. The fatal 2014 Oso Slide shut down Highway 530 for months. Another slide, an earthquake or some other major incident could create so-called “population islands,” cutting off residents from necessities indefinitely.

“It was a two-hour drive up through Skagit County to get to Darrington and that’s a real thing for our community,” said Scott North, spokesperson for Snohomish County’s emergency management department. “It happens, in a lesser degree, in every one of the hazards. When we have major windstorms, places get cut off. When we have snow, that occurs. The big shaky shaky, it’ll break us up into population islands.”

North added: “If someone says, ‘Yeah, you need to go now,’ there’s a reason. You may not be able to get out.”

Tips for evacuating in an emergency

• Assemble a “go bag” with changes of clothes, medicine, a first aid kit, water and other supplies.

• If you have pets, prepare pet food in a bag to save time as well.

• Save important documents in a fireproof safe.

• Do your homework ahead of time and know the best routes to get out.

Jordan Hansen: 425-339-3046; jordan.hansen@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @jordyhansen.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.