EVERETT — Even his family still has many questions about the man in the red checkered shirt, who was nameless for 44 years.

How did he go missing?

Why did he end up in the mudflats Jan. 3, 1979, at the western tip of North Spencer Island, where two sloughs twist together on the edge of Puget Sound?

What happened for him to break his left leg so badly, and then let it heal so poorly, leaving him with what would have been a painful limp?

After years of genealogical research and four decades of advances in DNA technology, investigators have finally answered an important question that could lead to more: his identity.

He was Gary Lee Haynie, born under another name in Topeka, Kansas.

The case marks yet another example of investigators using family tree research to crack a long-unsolved cold case. In addition to several homicides, forensic genealogy has led to breakthroughs in about a dozen local cases of unidentified remains since 2018. Snohomish County investigators now have only three such cases left to solve in the county.

In a phone call from Texas, cousin Hal Thayne said Friday: “It is a relief and closure to know about Gary.”

‘It just never came up’

He’d been born Gary Joseph Condomitti on Sept. 23, 1950. His mother Bernice Shafer and his biological father divorced when he was very young, from what Jane Jorgensen at the Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office was able to piece together.

Around 1955, his mother remarried to Sheldon Lee Haynie, who adopted him and renamed him Gary Lee Haynie, legally changing even his middle name to match his stepfather.

Thayne, now 71, saw his cousin Gary in person maybe twice in his life, when they were both kids. His uncle Sheldon served in the Air Force, so the family lived in places all across the country, from Kansas to New York City. Relatives would get together to go to the cemetery during the holidays, Thayne recalled, but the Haynies “never participated in that, really, because they were always far away somewhere.”

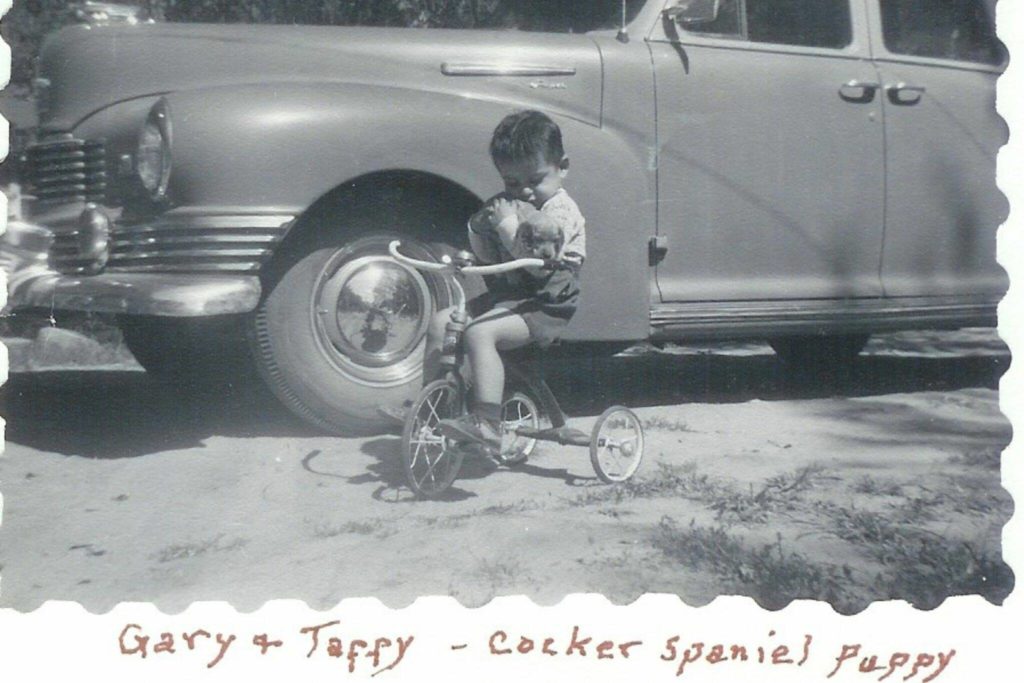

His clearest memories of his cousin are captured in precious few black-and-white pictures. Young Gary cradling a cocker spaniel puppy. Young Gary holding a bigger dog’s leash, beside his mother, in a pale dress, and his stepfather, in a white dress shirt and slacks. Young Gary with his front teeth peeking out from a half-smile on what looks like school picture day.

The boy, Thayne said, had some sort of a mental disorder. Given what he knows now, he wonders if Gary Haynie lived with autism. He’d heard another family member describe him as schizophrenic in adulthood.

“There was something that was amiss in his brain that caused people to notice,” Thayne said.

Haynie’s biological father Joseph Condomitti died at a Missouri veteran’s hospital when the boy was about 16. Then his mother died when he was 19. As far as investigators know, Gary Haynie never met any of his half-siblings. His adoptive father, meanwhile, finished his military service and worked for Boeing until he was ready to retire. He lived in the Everett area from the early 1970s until at least 1990.

“So we believe that Gary came out with him since he would have been his only family,” Jorgensen said.

Around the time he was last known to be alive, Gary Haynie was thought to be living in “some sort of rooming house,” she added. Social Security records list Haynie as having died on Christmas Eve 1976, but no surviving family members know who reported him as deceased. The family figures Sheldon Haynie lost track of his adult son around then.

Investigators who dug into the case in recent years could find no missing person report — but paper recordkeeping at the time was much shoddier than it is today. It’s possible the records simply got lost before they could be digitized.

In retirement, Sheldon Haynie lived the lifestyle of a snow bird. In winter he would drive to Baja California in Mexico, his nephew said. Once in the mid-1980s, he detoured to Texas to visit Thayne.

“There was never a conversation about Gary with him,” Thayne said Friday. “It just never came up.”

Sheldon Haynie lived his final days in Oregon. He died in 1997, never knowing what became of his stepson.

‘How he was discovered’

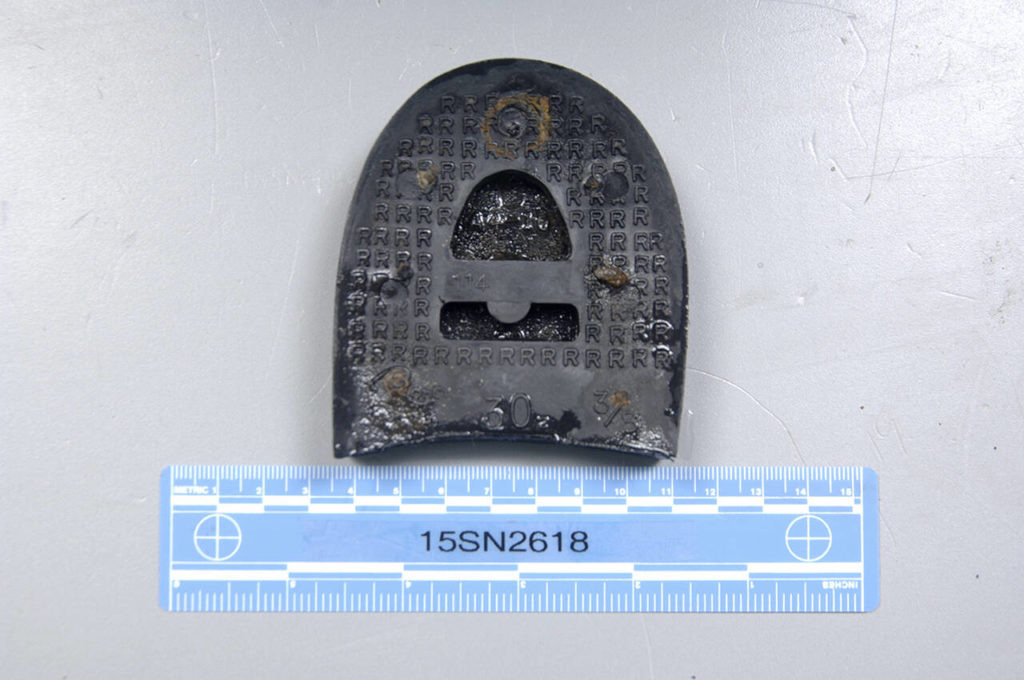

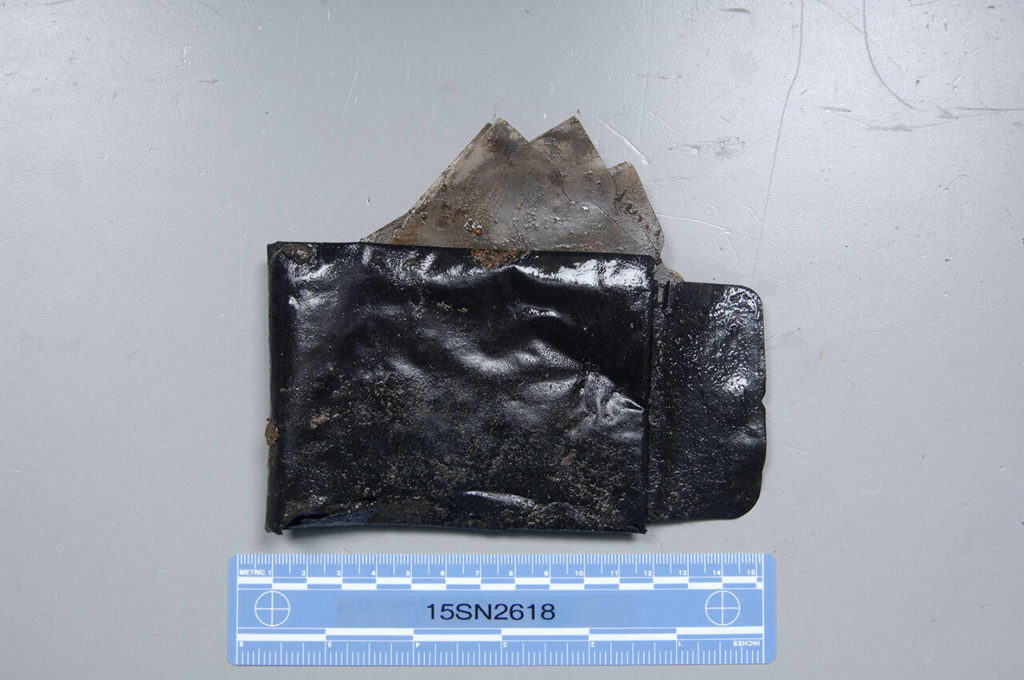

It was the first day above freezing in a week, in the winter of 1979, when a duck hunter discovered the remains entangled in fishing line. A shoe, a leg bone and a tan pair of pants were all together in the Snohomish River delta, by a 12-foot wooden piling. Near a fallen cedar, the hunter saw a red checkered shirt, then the skull, ribs and another black leather shoe with a foot inside.

It appeared the man had been dead for months. If so, Gary Haynie would’ve been pushing 28 years old when he died.

“It was — well, it was a shock to find how he was discovered, in pieces, in the mudflats,” Thayne said Friday.

Snohomish County sheriff’s deputies noted no obvious signs of foul play. Detectives believed he had likely been swept down the river, to the confluence of Steamboat and Union sloughs. Or he may have drowned near that resting place in the mud.

“We still don’t know how he died,” Thayne said, listing the possible fates. Drowning. Hitting his head on a rock. A medical emergency.

Snohomish County’s then-Coroner Robert Phillips labeled the deceased “John Doe (79-1),” with the cause of death “undetermined.”

Those sparse death records say the body would be examined and that his teeth would be charted, but those records do not exist today.

On March 15, 1979, the nameless man was buried at Cypress Lawn Cemetery in Everett, a practice that’s now outdated. Today remains are kept at the medical examiner’s office until they are identified. Investigators don’t know how many missing people were ruled out, if any, over the years.

In 2008, sheriff’s detective Jim Scharf and retired Superior Court Judge Ken Cowsert began unearthing dozens of cold cases in an effort to solve them with advances in DNA.

These remains were finally exhumed in 2015. Investigators gave him a new nickname: Spencer Island John Doe. A forensic odontologist uploaded dental charts to national databases in the hope of getting a match with a missing person. There were none.

The medical examiner’s office also entered the case into NamUs, a federal database of missing people and unidentified remains. No hits.

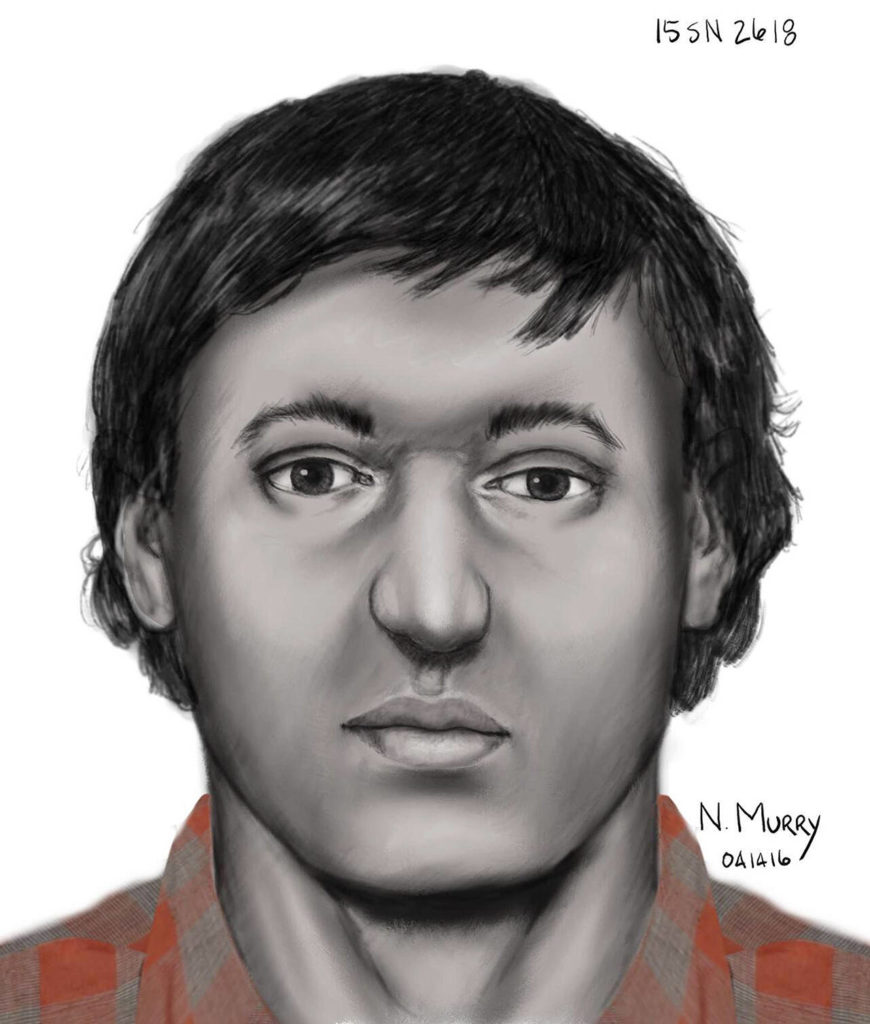

Forensic artist Natalie Murry reconstructed an estimation of the man’s face by gluing rubber pegs to the skull, then extrapolating how he would have looked. She drew him from the shoulders up, wearing a checkered red shirt.

Dr. Kathy Taylor, a state forensic anthropologist, examined the exhumed bones, too. She estimated they belonged to a man with Caucasian ancestry, who stood from 5-foot-2 and and 5-foot-6. She guessed he could be anywhere from 27 to 61 years old. She saw no “perimortem trauma” — that is, trauma at or around the time of death — but she did note an unset left femur fracture that had healed awkwardly. It would’ve left him shuffling around in pain, likely for years, about 2 inches shorter on one side.

A section of the right femur was sent to the University of North Texas to extract DNA and upload it to the FBI’s database, CODIS. Those samples were obtained by March 2019. Death investigators ruled out many possible matches through DNA and dental records, but still they were without a name.

The Daily Herald published an article in 2019, reciting basic facts, releasing photos from the case for the first time and giving people a tip line to call.

One retired police officer came forward, saying in the 1970s, he’d often seen a man around town with an awkward limp, who looked like the guy in the drawing. But he just couldn’t quite place the name.

‘I felt a draw’

In 2021, another piece of the John Doe’s femur was mailed to Othram, Inc., a private lab specializing in difficult DNA cases. Othram has helped Snohomish County investigators with several other remains cases in the past, extracting genetic profiles to upload to ancestry databases. That way, a genealogist can build the unnamed person’s genetic family tree, find his family and ultimately figure out his name. It’s the same process any amateur sleuth can learn these days to find their own long lost relatives, given enough time and patience.

DNASolves.com, an advocacy group that works to promote and fund DNA testing to solve unknown identities, cold cases and other violent crimes, funded the Othram lab work.

Months later, Othram had enriched enough DNA to plug the profile into GEDmatch. The public genetic database allows law enforcement to search genetic profiles in an effort to solve cold cases, if users grant permission.

Several investigators at the Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office worked to build trees based on some distant matches. Then they plugged the profile into another site, Family Tree DNA — and they got a fairly close match.

“It was like looking at 100 people versus 1000 people,” Jorgensen said.

It took maybe three hours of building family trees for death investigator Adam Wilcoxen to zero in on Gary Haynie. Investigators tracked down a surviving half-sister. And a DNA test confirmed they were biological half-siblings.

Snohomish County Medical Examiner Dr. Matt Lacy officially identified the deceased Feb. 10.

Announcing the identification this week, the medical examiner’s office noted Gary Haynie “traveled the world with his mother and adoptive father” and that he “loved the Beatles and played the piano.”

Mystifyingly, investigators couldn’t find any family members who knew anything about the badly broken leg.

Thayne is not a blood relative, since the two of them are connected by Gary Haynie’s stepfather, but he has been compiling family history for “years and years” on an ancestry website.

“It’s been almost ingrained in me that family’s important, and to keep connection with family,” he said.

He puts together a quarterly newsletter with his cousins, who live all over the West, in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah.

“I felt a draw to do something about his gravesite,” Thayne said. “We’re probably going to get a family to put a marker over wherever he gets reburied. But we have no relatives that live up there.”

Thayne still wonders what transpired between his uncle and his cousin. He wonders whether Gary Haynie got kicked out of the house, or left on his own, and exactly how he ended up in the river that day.

“This has opened up so many other questions,” Thayne said. “… And I’ll probably never really get answers.”

Aside from the drawing, he still doesn’t know what his cousin looked like when he grew up. He’s hopeful, however, now that Gary Haynie’s name is out there, that maybe somebody can help fill in some pieces of the puzzle.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.