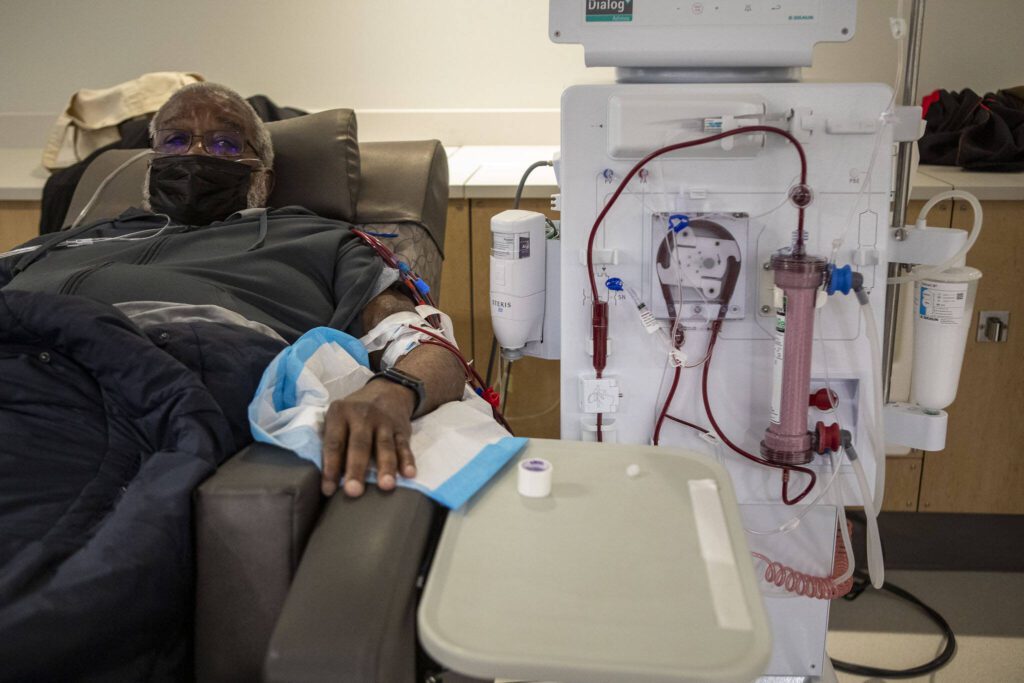

EVERETT — Three times a week, a machine cleans Harold Jones’ blood. Jones is squeamish about needles, and the treatment exhausts him. But it’s keeping him alive.

In 2022, Jones found out he had kidney failure, the final stage of kidney disease. His kidneys no longer function on their own to remove waste from his body, regulate his blood pressure or make hormones.

About 35 million Americans are living with kidney disease, but as many as nine out of 10 people don’t know they have it, according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

“Unfortunately, it’s a silent disease,” said Matthew Rivara, chief medical officer for Northwest Kidney Centers.

In 2019, about 20,500 people in Snohomish County had been diagnosed with kidney disease, according to estimates based on a national survey. But that’s a large underestimate of the actual prevalence, Rivara said. About 150,000 people in the county — more than the population of Everett — could be living with the disease, he said.

In 2020, the nonprofit opened a clinic in Everett, its first in Snohomish County. The nonprofit has a total of 20 dialysis clinics in Washington.

When Jones, 82, was diagnosed as pre-diabetic and later as diabetic, he “didn’t connect the dots” about his risk for kidney failure. Diabetes and high blood pressure, the most common causes of kidney disease, damage blood vessels and cells in the kidneys. Other risk factors include old age, autoimmune diseases and genetic kidney conditions.

“Also, we know from national data that when it comes to severe kidney disease or kidney failure, there are disproportionate impacts for non-white demographics,” said Kari Bray, a spokesperson for the county health department.

The most important step to detecting kidney disease early is regular visits to a primary care doctor, Rivara said. Tests for diabetes and high blood pressure will detect kidney disease. Keeping up a healthy body weight, low-sodium diet and exercise are other preventative measures.

Most people in the early stages of kidney disease feel normal, Rivara said. It’s not until Stage 5, also called kidney failure, that patients begin to show symptoms like fatigue, nausea and diminished appetite. But by then, the kidneys are functioning at less than 15% capacity, and the damage is irreversible.

“We all think we’re invincible until we’re not,” Jones said.

Before his diagnosis, Jones liked to travel, work in his yard and compete in his family’s bowling league. Now, his life revolves around dialysis and recovery.

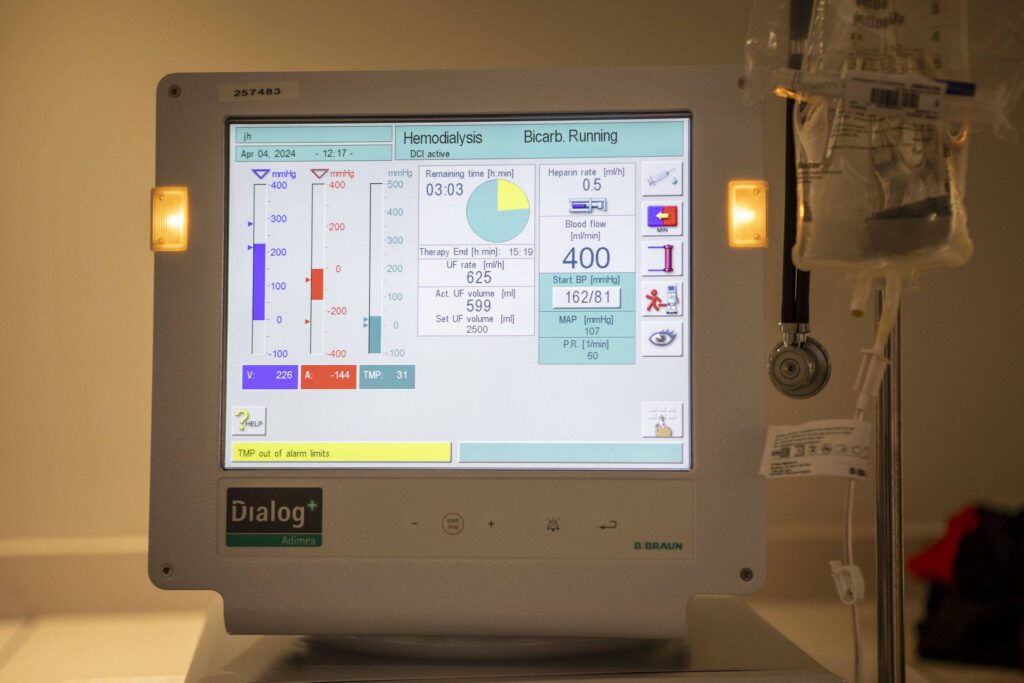

Each week at the Northwest Kidney Centers dialysis clinic in Everett, a machine pumps out and filters Jones’ blood, one cup at a time. The process takes about four hours. Jones is thankful for his family, who drive him to the clinic and care for him when he needs rest at home.

“This takes such a toll on me,” he said. “But I’m hoping I can get back to bowling soon.”

When it launched in 1962, Northwest Kidney Centers was the first out-of-hospital dialysis provider in the world. The nonprofit now serves 4 out of every 5 people who need dialysis in Western Washington. Most patients get in-clinic treatment, but the nonprofit also has a growing at-home program.

“Right now, there’s over half a million people in the United States getting dialysis who otherwise would not be alive,” Rivara said. “There’s no other technology that can allow people to live and thrive for so long after their organs fail.”

On average, people with kidney disease who start dialysis extend their lives at least five years, Rivara said. Without it, patients typically live weeks to months after their diagnosis.

Jones is on a rotating dialysis schedule with 50 other patients. He has developed meaningful friendships in his two years at the clinic. It’s comforting to meet people who are in the same boat, he said.

“One person, I don’t see around anymore,” he said. “I don’t want to ask the question. It’s too distressing.”

The best treatment for kidney disease is a kidney transplant, but the waitlist can be up to six years. And for patients like Jones, the surgery’s risks are too great. He applied to be a University of Washington transplant recipient, but was denied because of his age and health condition.

Jones wishes he knew more about kidney disease earlier in life, he said. He would have visited the doctor more often, and limited his salt and sugar intake.

While receiving dialysis treatment last week, Jones reflected on his life with his wife of 57 years, who he’s traveled the world with. He talked about his three kids and five grandkids.

“I’ll be doing dialysis forever, or until I … ” Jones paused and motioned to the sky.

“But if I was to leave here tomorrow, I know I lived a blessed life.”

Sydney Jackson: 425-339-3430; sydney.jackson@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @_sydneyajackson.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.