EVERETT — Kathleen Waldron was a flight attendant in January 1970 when the first Boeing 747 was delivered to Pan Am, the airplane’s launch customer.

Waldron, along with other Pan Am attendants, was soon in training to keep passengers and crew safe aboard the big bird.

“It was so different and so big,” she said of the 747, the world’s first wide-body plane. It was 2½ times bigger than the largest airliners of the day: the 707 and the Douglas DC-8.

“We had to learn how it worked, how to get out of it. It was a little scary not having the pilots up in the nose, not having them on the same level,” she said of the plane’s design.

More than 50 years later, the 747’s majesty is still intact.

“I still can’t believe it can fly! When it comes in, it glides. It’s still jaw-dropping,” Waldron said.

The last 747 built — tail number N863GT — rolled out of The Boeing Co.’s assembly factory at Paine Field in December.

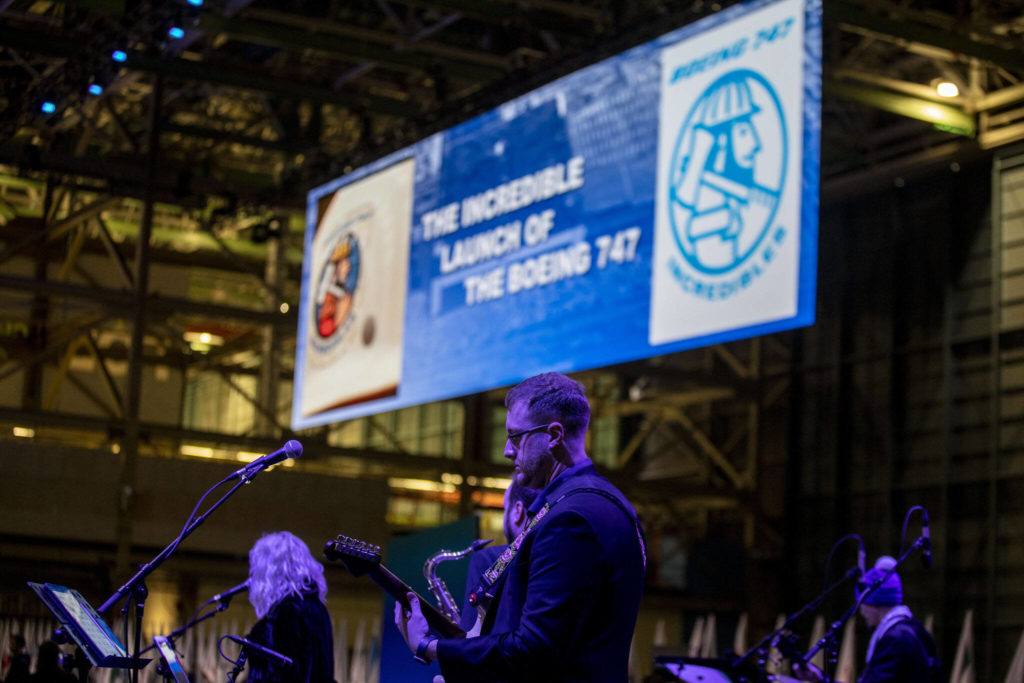

On Tuesday, thousands of Boeing employees and dignitaries gathered inside the Everett plant to honor the airplane’s legacy and deliver the last 747 to the final customer, cargo carrier Atlas Air.

Former Boeing CEO Phil Condit was there, along with current CEO David Calhoun and Atlas Air CEO John Dietrich.

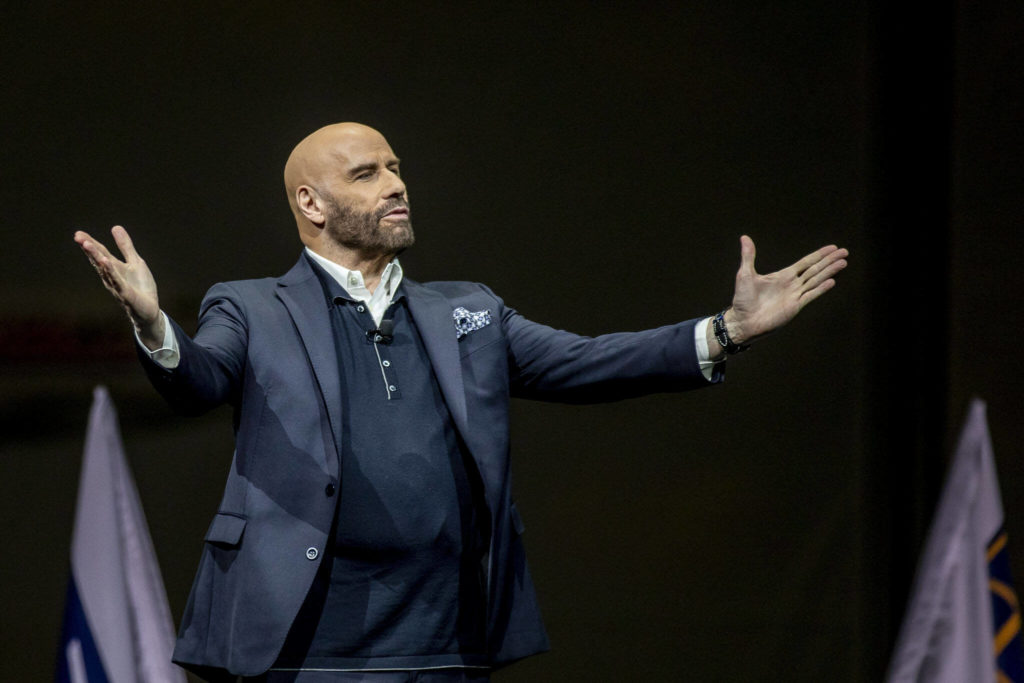

And so was actor John Travolta.

“I had to be here in person. As a pilot I know how great this plane is to fly,” said Travolta, who is licensed to fly the 707, 737 and 747 models.

Since 1969, more than 1,500 of the six-story tall, four-engine jets, built only in Everett, have been produced.

Frank Abadi was in his 30s when he was hired by Boeing in 1962.

The 91-year-old structural engineer was there for the rollout of the first 747 in 1969, the first flight and the tests that followed. Abadi, who worked on the 747 program from 1967 to 1982, retired from Boeing last year after 60 years. On Tuesday, he returned to the Everett factory for the 747 sendoff.

“It’s good to be here. I love this airplane,” Abadi said. “I know every piece of that airplane.”

Dozens of airline representatives, each carrying the flag of a 747 customer, gathered on the makeshift stage inside Building 4-21.

At the front of the line, Charles Trippe, grandson of Pan Am’s founder Juan Trippe, hoisted Pan Am’s flag. It was Juan Trippe who famously told Boeing CEO Bill Allen in 1965 that if Boeing produced the world’s first jumbo jet, he would buy it. At the end of the line, was the Atlas Air flag.

Elizabeth Lund, senior vice president and general manager of Boeing Commercial Airplanes, reminded the audience of the 747’s varied roles through the years: Dreamlifter, Air Force One, firefighting supertanker, space shuttle carrier. The 747 is still a workhorse whose “legacy will continue,” Lund said.

Carsten Spohr, Lufthansa’s CEO, arrived in style, flying from Munich to Seattle aboard one of the airline’s 747 passenger jets. The 747 still takes his breath away. ”It’s a damn beautiful airplane,” Spohr said.

“This is a milestone event,” said Atlas Air CEO Dietrich, whose company operates 56 of the 747s and the four Dreamlifters, 747s modified to carry oversize cargo. As he spoke, the doors of the building opened to reveal the 747, now wearing the airline’s blue and gold livery.

“We all share in a deep admiration for this guest of honor, the Queen of the Skies,” Dietrich said.

The final speaker, Boeing CEO Calhoun, thanked the Incredibles — the workers who launched the first 747 and “everyone who has ever touched the plane.”

On Monday, Calhoun announced that the Everett factory would begin building some 737 Max airplanes.

This last 747 bore a special insignia on its nose, a memorial to the late Joe Sutter, the program’s chief engineer who led a team of 4,500 engineers and machinists that developed the jet.

In the late 1960s, they worked with slide rules and hand drawings to design the hump-nosed, four-engine plane and its 4.5 million parts.

From her home in Port Townsend, Waldron watched a live stream of the event.

Waldron recalls her worries when she first stepped aboard a 747. How would she be able to care for the more than 300 passengers?

“And then I remembered, I was only responsible for my section,” said Waldron, who later earned a master’s degree and worked as a college counselor. “We were a little city. We dealt with emergencies, sick people. We played the role of doctor, nurse, firefighter, police. As flight attendants our primary responsibility was to take care of people.”

Time has not lessened the big bird’s impact for Waldron and so many others who helped build it, flew it or admired it.

“Every time I see a 747, I have to stop and watch,” Waldron said. “It’s like watching an eagle — they’re the eagle of the skies.”

Janice Podsada: 425-339-3097; jpodsada@heraldnet.com;

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.