ARLINGTON — Between acquiring property, creating channels for fish and planting native vegetation, just one salmon recovery project can take decades.

But to help salmon populations rebound, especially the threatened Chinook, members and employees of the Stillaguamish Tribe said they are doing all they can to support this “cornerstone” of their culture.

This year, the tribe received over $1 million in grants from the state Salmon Recovery Funding Board and the Puget Sound Partnership, helping propel two projects.

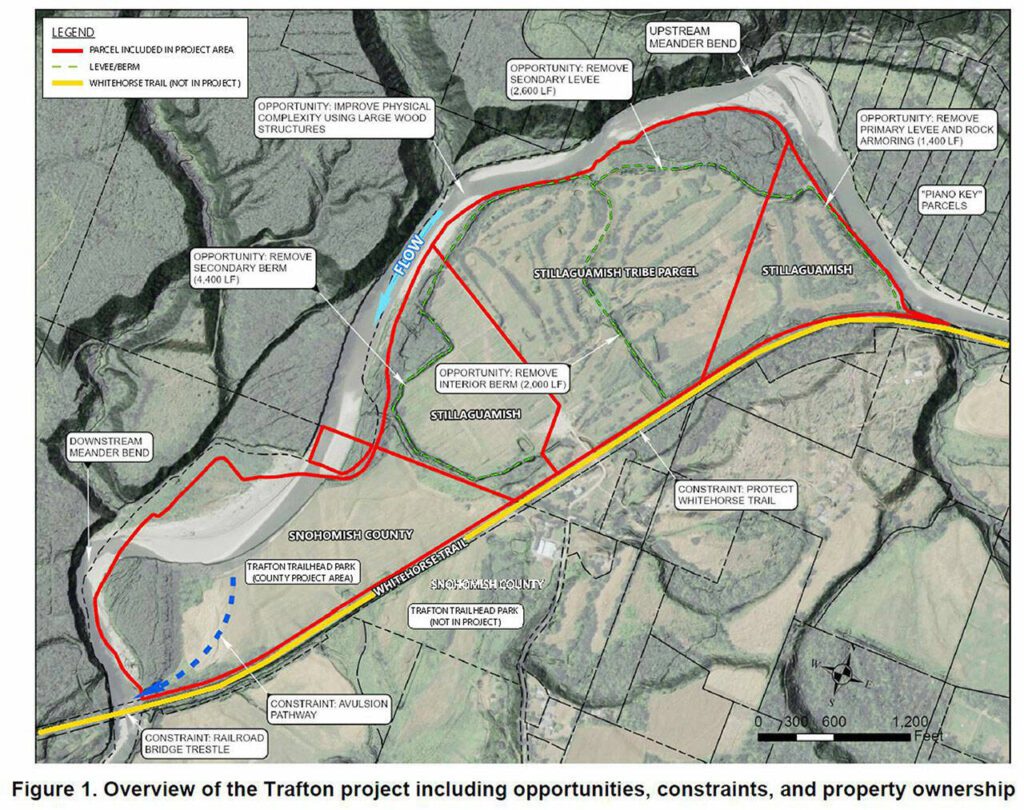

In one, the Stillaguamish Tribe plans to improve the Trafton floodplain along the North Fork Stillaguamish River, about 4 miles northeast of Arlington. In the second, the tribe will plant trees and bushes in a separate area along the North Fork, west of Darrington. Establishing a riparian forest provides shade for fish and helps prevent soil from falling into the river.

The Trafton site will be the largest floodplain project in the Stillaguamish River, said Jason Griffith, environmental manager for the Stillaguamish Tribe. About 158 acres are owned by the Stillaguamish Tribe and another 72 acres are owned by Snohomish County through Trafton Trailhead Park.

Thousands of pieces of wood will create logjams in the main North Fork channel, with a new side channel set to be built, too.

Historic aerial photos of the Trafton property show large logjams and channels flowing across the entire width of the floodplain.

“It was always obvious to me, looking at the photo record, that it was … a site with a lot of potential for salmon recovery, for habitat restoration,” Griffith said.

Logjams are complex, Griffith said. They slow the river’s flow, provide cover for adult and juvenile salmon and can foster aquatic plant growth.

“The river’s productivity is directly linked to the complexity of the habitat,” Griffith said, “and the river’s been simplified a great deal over the last 100 plus years.”

The Stillaguamish Tribe plans to begin construction of the Trafton project in 2025. The project is split into two phases. It’s expected to take at least four years. In phase one, workers will move dirt, excavate a side channel, create logjams and remove invasive plants, so new native vegetation can thrive. Phase two will consist of removing an almost mile-long levee and placing more logjams in the river.

A portion of Whitehorse Trail, a 27-mile stretch connecting Arlington to Darrington, cuts through the Trafton floodplain. Griffith said logjams and plants will be placed strategically to keep the river’s energy away from the trail. Maintaining a “recreation corridor” has been a significant aspect of the project’s design, Griffith said.

Kadi Bizyayeva, deputy fisheries manager for the Stillaguamish Tribe, said the tribe restricts access to Chinook and steelhead by reducing the number of fish that can be harvested and restoring habitats. But still, “there’s a lot of culture that gets removed from our community,” Bizyayeva said.

“Decolonizing the landscape” — by removing structures inhibiting habitat restoration and making project sites more climate-resilient — can foster a functioning and healthy ecosystem, Bizyayeva said.

“Then we ourselves are functioning and healthy,” she said.

The Stillaguamish Tribe has an oral tradition outlining what the valley around the Stillaguamish River used to look like. The valley of years past is very different from what it looks like now, Griffith said.

Acquiring property along the Stillaguamish River and rewilding natural areas are part of a tedious process. But salmon “are an indicator of a much larger ecosystem,” Griffith said, recounting how bear, deer and elk have responded to the tribe’s restoration efforts in the past.

Griffith said: ”We’re trying to restart, repair, restore the natural processes that create and sustain salmon habitat.”

Ta’Leah Van Sistine: 425-339-3460; taleah.vansistine@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @TaLeahRoseV.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.