SNOHOMISH — For Jeanette Westover, the pieces finally clicked in late February.

After seven months living in Unit 3 at Pilchuck Place apartments in Snohomish, Westover had been to the hospital four times.

Her skin itched and burned. Her memory got worse. She struggled to complete tasks.

“There is no way to describe it other than that you know you’re dying, but you don’t know why,” Westover said in an interview last week.

One particularly frightening symptom came when Westover, who also has autism, suffered seizures after turning on the heat in her Housing Hope-owned apartment on Avenue E.

“Eventually, I discovered a silent, non-smelling thing that was killing me,” she said.

That silent killer was meth.

Every time Westover turned on the heaters, she was blowing toxic chemicals through the air.

Earlier this month, an analysis of Westover’s apartment at Pilchuck Place found meth residue exceeded 300 micrograms per 100 square centimeters in Westover’s bedroom, according to results shared with The Daily Herald.

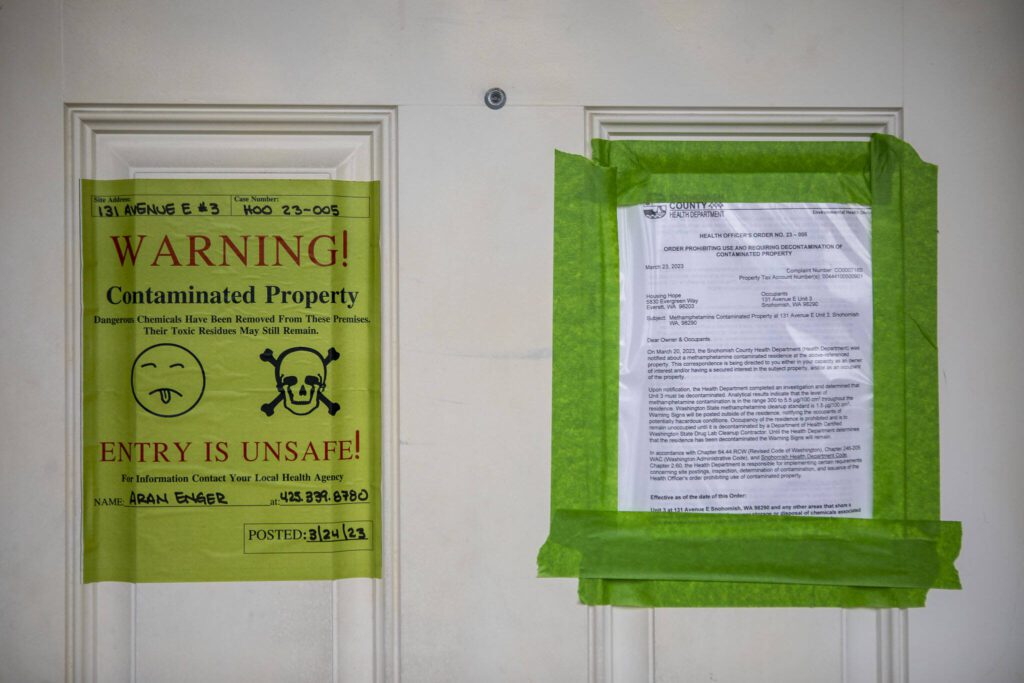

That’s more than 200 times the level of contamination permitted by the state. Once the limit is exceeded, the space must be decontaminated, according to the state Department of Health. On the door of Westover’s unit Tuesday was a notice from the county health department saying no one could stay in the apartment until the contamination was cleaned up.

A neighbor told Westover the previous tenant in her apartment may have operated a meth lab there. Before Westover moved in, tenants reported drug issues in the unit, said Joshua James, who managed the building at the time for Housing Hope.

The tenant who alerted Westover, who requested anonymity out of fear of retribution, said she called police and Housing Hope about the drug activity several times.

James said Housing Hope officials were aware of the contamination. But when the purported lab operator left, there was no cleanup of the meth, Westover claimed.

“Why would you move someone into an apartment where there was a drug operation?” Westover’s neighbor said. “You can’t tell me they didn’t know.”

The meth residue in Westover’s apartment has raised questions about the safety of neighboring units. Testing found levels of contamination “well below Washington State’s cleanup guideline,” but that hasn’t stopped one tenant from living elsewhere.

Housing Hope is a Snohomish County nonprofit offering over 500 affordable housing units across the county. Right around the time Westover discovered the contamination in her apartment, Housing Hope officials cut the ribbon for its largest project yet: a 60-unit complex in Marysville.

James called it a “flagrant disregard to what they stand for.”

“Housing Hope should’ve known better,” the former property manager said.

On Monday, the Everett-based organization reported its “records show no complaints or evidence that this unit presented health issues when transitioned between tenants.”

Westover, however, said tenants had been complaining for years about the apparent meth lab. Catherine Taylor, who lived next door, said the same.

Housing Hope also said in a press release it was “working on immediately remedying unit #3, removing all surface materials in the space down to the studs.”

“Housing Hope takes the safety and welfare of our tenants very seriously,” the provider said in a press release. “We will continue to guide our work deferring to industry and state-certified professionals on any remediation needed for the improved safety of our tenants and staff at Pilchuck Place and any of our properties as required.”

Westover’s friend Susan Jones said it’s too little too late.

“This literally almost killed her,” Jones said.

‘Disrespected and discarded’

Westover moved here from Texas last year to volunteer for AmeriCorps.

HopeWorks, an affiliate of Housing Hope working with AmeriCorps, got Westover a one-bedroom apartment at Pilchuck Place at 131 Avenue E in downtown Snohomish, she said. The complex has 10 units.

HopeWorks told her it would be a good spot for her. Her stipend for volunteering paid the $1,100 rent.

Westover called the apartment “beautiful.” Little did she know, every time she took a bath, turning the fan on made the bathroom a “fume box,” Westover said.

One person Westover had over to the apartment even accused her of drugging him because of how he felt there.

Meth exposure can have both short- and long-term effects, state health department spokesperson Roberto Bonaccorso wrote in an email. Those include increased blood pressure and erratic behavior in the short term, and permanent brain, heart, kidney or liver damage in the long term.

Westover has had several kidney infections since living at Pilchuck Place, she said.

She fears lingering health issues from her prolonged exposure. And she’s afraid to get a brain scan because she doesn’t want to know the results.

“I have no idea what kind of mental calamity I’m going to face from this kind of trauma,” she said.

Testing also found meth contamination far exceeded state guidelines throughout the apartment, not just in the bedroom. In the living room and kitchen, Bio Clean, a contractor certified by the state, found 91 micrograms per 100 square centimeters. In the hallway, it was 64. In the bathroom, 39.

Westover moved out in late February with the help of T’Naya Ramirez, an advocate with the Tenants Union of Washington State. Ramirez got Westover an Airbnb in Snohomish.

In the meantime, Ramirez started an online fundraiser to raise money so Westover can pay for housing.

“She’s been strung along for about a month now, and thankfully, again, the community has come in, but it shouldn’t had to have been this way,” Ramirez said.

On March 17, the advocate notified the county health department about the contamination concerns, department spokesperson Kari Bray said in an email. After reviewing the Bio Clean lab results, the health department directed Housing Hope to remediate the contamination.

“The responsibility for remediation is with the property owner,” Bray wrote.

Westover feels Housing Hope has been hiding from accountability for the contamination. She’s disappointed.

“I feel I’m being disrespected and discarded,” she said.

Westover still worries about the other tenants remaining at Pilchuck Place, low-income residents who don’t have a place to go.

“I don’t think that this is the end,” Ramirez said. “I think that this is just the beginning of something much, much bigger, unfortunately.”

Bio Clean conducted more tests last week in two units that share walls with Unit 3, according to Housing Hope. Those tests revealed meth levels below the state limits.

But Taylor, who lives in an apartment next to Westover, believes those tests weren’t thorough.

She had previously suffered from nonepileptic seizures. But in the winter months, when she turned on the heat, they got worse, Taylor said. It also burned under her skin. In early March, she left her apartment over the meth concerns.

“It doesn’t just affect Jeanette,” she said. “It affects everybody.”

Taylor has been living with a relative because she doesn’t feel safe there.

She said: “I still don’t trust what they’re doing.”

Jake Goldstein-Street: 425-339-3439; jake.goldstein-street@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @GoldsteinStreet.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.