EVERETT — “Save the gazebo.” “Preserve history.” “No demo.”

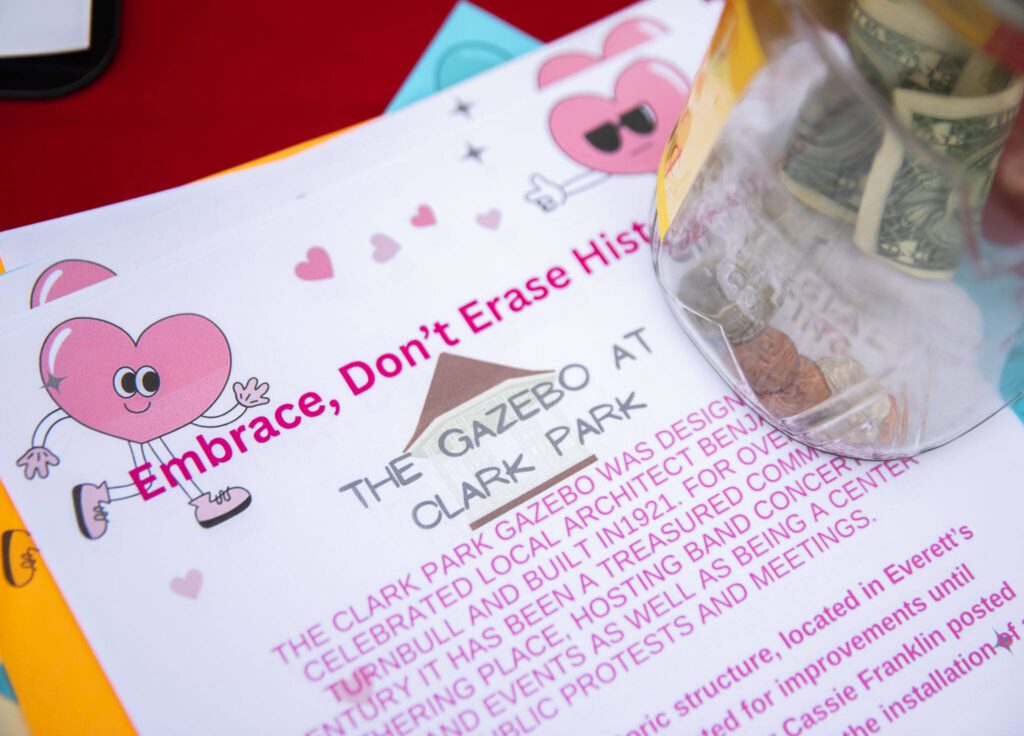

Over the weekend, a small crowd decorated the Clark Park gazebo in hearts, sparkles and messages of love for the structure built in 1921.

Late last month, Mayor Cassie Franklin announced on social media that the city “will be removing the gazebo” to expand a dog park, citing “safety issues” and “community concerns.”

In response, the nonprofit Historic Everett held a “heart-bombing” at the gazebo Saturday, calling on city leaders to preserve the century-old structure.

“Clark Park is the oldest park in the city, the gazebo is its most character-defining feature,” said Jack O’Donnell, a longtime Everett resident and historian in an interview with The Daily Herald. “This is just something that’s too much Everett to throw away.”

He added that preserving historic property should be in the city’s budget. If something is too old too move, that’s all the more reason to try and preserve it, he said.

“I got to thinking, what kind of a city would get rid of something that’s so important?” he said. “I love Everett dearly, but it still makes me question my hometown.”

Clark Park, located two blocks east of Everett High School, has long held “an unsavory reputation for crime and vandalism,” as a Herald article reported in 2011. In recent years, the park has been the site of drug-related arrests, stabbings and petty crimes.

Parks are exempt from the city’s no-sit, no-lie zones, created in 2021 to deter homeless people from gathering in certain areas. This makes Clark Park and the gazebo one of the only places for homeless people to seek refuge from the weather without facing fines or jail time.

The sudden announcement to remove the gazebo shocked those on the city historic commission and parks board, who said they had no idea of the city’s plan until the mayor’s post. A year ago, the city was in talks with the historic commission and parks department to either remodel the gazebo or move it elsewhere.

“The city has considered several options including moving/storing the gazebo, closing it off completely, making updates to it and removing it,” city spokesperson Simone Tarver said via email last month. “After considering these options, the decision’s been made to remove the gazebo.”

Tarver followed up in an email this month: “We’ve now reached a point where it needs many costly repairs. In addition, moving it to another city park would be cost-prohibitive — between $163,000 and $230,000 depending on which park.”

A remodel could cost up to $400,000, according to the city.

The city hasn’t confirmed a removal date. As of Wednesday, public permit records did not include any mention of demolition at Clark Park.

O’Donnell said removing the gazebo won’t do anything to solve homelessness, and that there’s “certainly” enough room for both a dog park and the gazebo.

‘Neglected and idle’

When Everett purchased Clark Park in 1894, the nation was still in the throes of a depression after the Panic of 1893. The city’s largest employer, Everett Land Company, had slashed wages by 60% for those lucky enough to still be employed. However, residents still felt it was important to put aside money for a city park.

The city’s budget was $60,000 in 1893, with only $30,000 in revenues, according to Everett Public Library archives. Still, residents overwhelmingly voted in favor of a $30,000 park bond that year.

“One of the most influential and profitable educators among civilized nations is the elevating influence of public parks,” said Everett Mayor Norton Walling in 1894.

In 1921, with the local economy showing signs of improvement, the city spent $20,000 to build the gazebo. The structure was designed by Benjamin Turnbull, who also built other iconic historic buildings in Everett, such as the Commerce Building and Hodges Building downtown, and the Challacombe & Fickel funeral home on Oakes Avenue.

The park was originally named City Park, but was renamed in 1927 to honor one of the city’s founding residents, John J. Clark.

In its early days, bands used the gazebo for summer concerts. This continued through the 1960s.

Clark Park was a popular place for protests, and was one of the few public parks where religious gatherings were permitted. In 1981, half of the park was sold to Everett Public Schools, which put six tennis courts on the property, according to a history of Clark Park put together by the Bayside Neighborhood Association.

The park and gazebo began to decline in the 1980s, according to newspaper archives.

In 1981, Traci Lynn Thompson discovered this firsthand when she eyed the gazebo as a possible wedding venue, The Herald reported at the time. However, the gazebo was hardly photo-ready.

“The problem was, the gazebo, sitting neglected and idle in the center of a neighborhood park surrounded by houses and churches, had been vandalized and otherwise abused by people and weather,” Herald writer Pam Witmer wrote. “Covered with graffiti, a portion of its railing gone and its paint grey and peeling, the gazebo didn’t look like the site for the storybook wedding Thompson’s bride wanted.”

The parks department paid for paint and supplies, so the groom, Michael Thompson, and his friends could give the gazebo some life before their big day.

‘Once it’s gone’

In 1994, local contractors and business owners donated supplies and labor to rebuild the gazebo, according to library archives. Around that same time, the city put the gazebo behind a chain link fence, only to remove it for events.

The city also placed a new roof on the gazebo in 2006, according to city permit records.

In 2003, Bayside Neighborhood Association chair Elle Ray started a petition to remove the fence. About 50 people signed. They gathered at the park to tell stories of their memories there, according to the history project created by the neighborhood association.

“You could see people were energized and animated when they talked about the gazebo and the park,” Ray wrote in 2004.

Ray had a special relationship with the park, using it as a place to find solace while her then-husband was away during the Vietnam War.

“On summer days she would sit near the gazebo, where the simple structure and towering, graceful chestnut trees gave her a sense of peace,” the history project read.

“The park was so simple; it had no connection to the other things that were going on in the world,” Ray said, according to the history project. “It was a place that wasn’t a part of the turmoil.”

The fence remained, on and off, for about 20 years. It was finally removed in 2021.

This year, the Bayside Neighborhood Association voiced support for the city’s choice to remove the gazebo, stating that a dog park “will be a space that the neighborhood can more fully utilize.”

O’Donnell sees it another way.

“The neighbors don’t want it because of the problems they see, but I think it’s more than a neighborhood issue, it’s a city issue,” he said. “I just think it has to stay here. I think that the city is making a big mistake. Because you know, once it’s gone, it’s gone.”

Ashley Nash: 425-339-3037; ashley.nash@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @ash_nash00.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.