DARRINGTON — Sandra Ruffner and her hiking partner noticed a tuft of smoke wafting from the steep hillside above the Downey Creek Trail on Sept. 12, on their way back from a 30-mile backpacking trip.

Curious, they approached to find a 6-inch flame smoldering in the moss.

“It was not a big deal,” Ruffner said. “It wasn’t scary.”

So she pulled out her camera and took some photos.

A few minutes later they came across another smoking patch. Then they hiked past flames lapping at the trunk of a dead tree. As they kept going, smoldering moss and scattered flames gave way to downed trees with roots eaten by fire.

“That’s when I kind of stopped taking photographs, because now, we really gotta get out of here,” Ruffner said.

One trunk had been entirely hollowed out, but its green leaves were untouched.

With little to no cell service in the Glacier Peak Wilderness, Forest Service rangers had no way of warning at least 20 hikers on the trails about the wildfire headed their way.

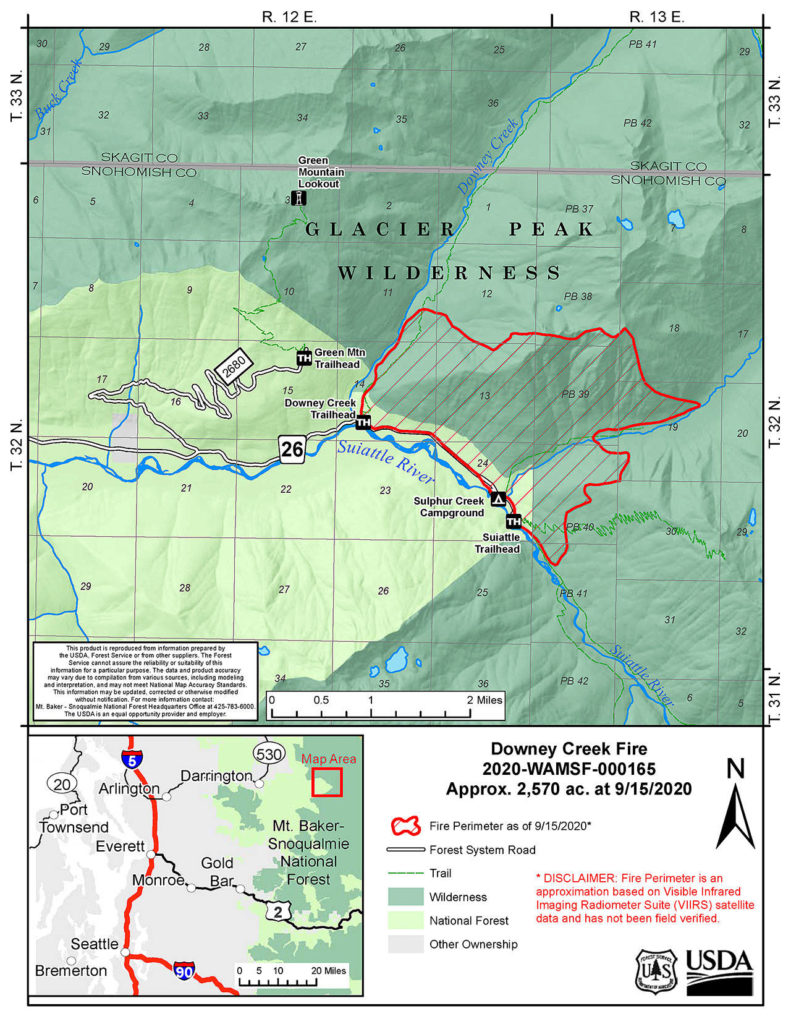

A lightning bolt sparked the Downey Creek fire back on Aug. 16. It inched forward for weeks before multiplying from 350 acres to over 1,000 in the span of a day in early September. Its growth tapered off at 2,600 acres.

In late September, a tendril of white smoke rose among old-growth trees in the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, wafting upward to join the orange haze from Oregon and eastern Washington wildfires already blanketing the sky.

Against the smog, fresh smoke from the the Downey Creek wildfire east of Darrington was barely discernible.

Earlier this month, Washington wildfires swiftly destroyed entire communities and scorched almost a million acres, according to the Department of Natural Resources.

Gov. Jay Inslee dubbed them “climate fires,” a product of the low humidity, high temperatures and howling winds that are becoming more frequent as the state’s climate changes.

The Downey Creek Fire wasn’t like the wildfires in eastern Washington, where low precipitation and high temperatures turned grass and brush into kindling. The west side of the Cascades got a normal amount of rain this summer. So the Downey Creek Fire burned without engulfing every tree.

From the Downey Creek Bridge, it was hardly visible in late September. It had gone west in the ground to its namesake creek and east to Sulphur Creek. The fire never threatened the nearest town, Darrington, about 17 miles to the east.

Rangers were focused on evacuating hikers from backcountry trails and clearing Forest Road 26 of continually falling trees.

The route, also known as Suiattle River Road, is the only way out by car. Several groups had hiked about 15 miles from a trailhead at the end of the road, to an elevation of 6,000 feet on Miners Ridge. From camps at Image Lake, seven backpackers saw a plume of smoke rising into the sky.

Forest Service wildlife biologist Phyllis Reed was staying in the Miners Ridge fire lookout with her husband. As a veteran wilderness ranger, Reed is familiar with the many trails to and from Image Lake. She radioed incident command at the trailhead. Hikers sheltered in place at the lake. They camped two nights before heading back down the trail. Reed packed up and headed out with them, so they had a way to maintain radio contact with incident command.

Two miles from their cars, they met the fire’s advancing frontline. Flames on the slope above the trail spread as burning twigs rolled down. Walking single file and 15 feet apart, the group reached safety and escaped.

During their descent, the Forest Service hauled out many trees falling across the forest road, so hikers could caravan back to the highway.

Meanwhile, at trailheads along the road, Snohomish County sheriff’s deputy Peter Teske had worked to track down others out in the backcountry by collecting license plate numbers to identify their owners. He got in touch with family members to find out where the hikers had planned to visit.

He located 18 people trapped on the other side of the fire.

“Many of the hikers were very, very scared as trees were falling nearby and you could hear cracking and breaking every few seconds,” Teske said in a statement relayed by the sheriff’s office. The deputy has since gone on vacation, and he was not available to be interviewed for this story.

It takes three specific conditions for wildfires to spread in the wilderness east of Darrington: extended dry weather, an easterly wind and a steep slope, Forest Service Incident Commander Denny Coughlin said.

The Downey Creek Fire had all three ingredients.

It ran downhill first, among underbrush in small spot fires. As the flames moved east and west, the fire cut another path uphill, Coughlin said. The fire hollowed layers of duff, the decaying organic material that holds the trees steady.

It was far from all-consuming, Coughlin said. Many Douglas firs and larger cedar trees will survive.

Ground fires like this are some of the most dangerous for firefighters. That’s because heat can creep underground as it burns up roots, Coughlin said. Firefighters might step onto what looks like solid ground, only to fall into a pit of hot ash.

Heavy rains last week reduced the Downey Creek Fire to a smolder. It’s expected to keep burning until winter weather puts it out, Coughlin said. In the coming weeks, biologists will examine the burned forest for damage to habitats like Sulphur Creek, a salmon-bearing stream.

Forest Service staff will also look for impact to bridges and trails. Many roads, trails and campgrounds in the area have been closed, and it’s impossible to say when they will reopen.

“We don’t make these decisions lightly,” ranger Jim Chu said.

Weak and fire-damaged trees will continue to fall.

The fire drastically altered the treeline, leaving big gaps between trunks. Moss- and twig-covered ground turned an ashy gray. When the forest regrows, it will be a mosaic of new foliage and old-growth trees, Coughlin predicted. Larger trees, some nearly 500 years old and 9 feet in diameter, have burn marks from previous wildfires. Small fires thin out over-crowded parts of the forest, creating new habitats and reducing the risk of big wildfires in the future.

Large fires happen in this area about every 300 years, Forest Service Prevention Technician Francesca LaManna said. The Downey Creek area was due.

Wildfire “can be a good thing,” Coughlin said.

“It allows the natural process of that natural area and allows the forest to do its thing,” Coughlin said.

In cases like the Downey Creek Fire when the flames aren’t endangering homes, the Forest Service manages the fire’s borders without trying to contain it.

Ultimately, nobody has been hurt by this wildfire.

A hiker from Tacoma was the last to leave. His was the final car parked at a nearby trailhead. Minutes after he drove out of the burning area, rangers heard a massive boom like a gunshot — and then, “crack, crack, crack.” A tree fell across Forest Road 26, right where he had just been.

Herald writer Stephanie Davey contributed to this report.

Julia-Grace Sanders: 425-339-3439; jgsanders@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @sanders_julia.

How to prepare for wildfire season in the backcountry

Fires grow quickly in the Pacific Northwest between July and September, according to the U.S. Forest Service. Especially during that time, tell someone your plans and carry a communcation device that works without cell service, like a locator beacon with satellite texting.

Backcountry visitors are encouraged to check in with local ranger stations for trail and road conditions; pay attention to the forecast; have backup plans for an alternate trip; know alternative exits; pack the Ten Essentials and know how to use them; and bring extra supplies in case a trip becomes longer than expected.

Fire can spread quickly — many times faster than you can run. If you see smoke while hiking, remain calm but leave as soon as possible. Try to figure out where the smoke is coming from and avoid that area. Be prepared to leave vehicles at the trailhead if they become blocked or if it’s not safe to leave.

Find more tips for hiking during wildfire season through REI, the Washington Trails Association and the Pacific Crest Trail Association.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.