TULALIP — In a cemetery he once maintained, the tribal elder was laid to rest Wednesday.

There was an honor guard for the veteran who returned alive from war to the Tulalip Indian Reservation 64 years ago but whose brother did not.

Nearly 60 years ago, Ray Moses saw to it that the tribes created an honor guard. He didn’t want another Memorial Day to pass without one. Early on, he borrowed rifles and ammo from the Veterans of Foreign War chapter in Marysville with a promise of returning them on time for their ceremonies.

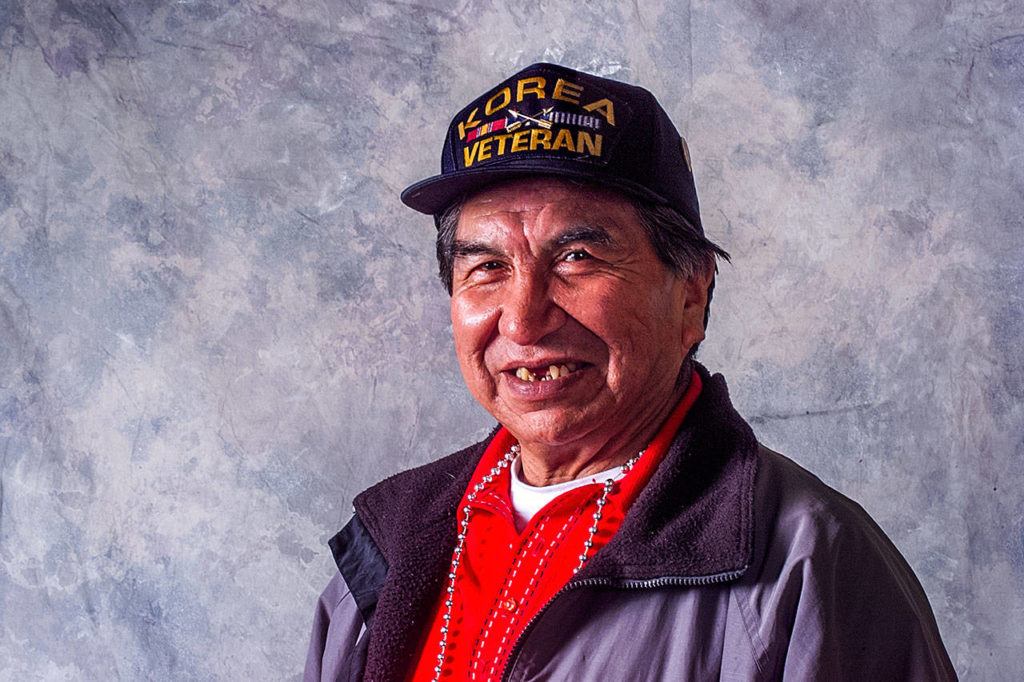

Moses was proud of his military service and his Native American heritage. He was often seen wearing a black baseball cap with yellow “Korea Veteran” stitching above the bill. He kept a folded, dog-eared copy of the Point Elliot treaty in his back pocket. To the treaty tribes — today’s Tulalip, Stillaguamish, Lummi, Swinomish and others — the 1855 pact signed near Mukilteo’s shore tells everyone what belongs to them, forever.

He’d hold the tattered paper up in the sunlight and wave it at passersby.

“People don’t know that we have these rights,” he’d say. “They need to know this.”

Moses died March 2 with family by his side. He was 87. He’d grown weak in the final months. From his bed, he’d whisper greetings to visitors, remembering nicknames he’d given cousins long ago. Sometimes, he’d just squeeze their hands. He’d listen to a recording made by his mother in the early 1960s. It was of tribal drummers, many from his family. He would raise a hand, often with closed eyes, and keep time with the beating of the drums.

Moses was a tribal storyteller and historian. He shared his knowledge of ancestral burial sites when developments were being considered. He provided testimony in the landmark Boldt decision, a 1974 federal court ruling about treaty rights that found Washington tribes were entitled to half the salmon and steelhead harvest in their traditional fishing grounds.

He and his mother, Marya Moses, were early advocates of the tribes’ Lushootseed language program. Marya was one of the tribes’ last native speakers and linguists spent years tapping her knowledge in an effort to preserve the language.

Ray Moses would often drop by the tribes’ language department in its early days to offer encouragement.

“He always supported us,” said Toby Langen, a longtime teacher in the program.

Ray Moses was also a favorite when third-graders across the Marysville School District took field trips to the tribal longhouse. He’d tell stories passed on over generations, how the whale pushed the reluctant salmon back into the rivers or how the beaver tried to woo the field mouse.

“He loved it,” said Johanna Moses, one of Ray’s sisters. “He liked to see the little kids’ faces.”

Ray Moses patiently and sometimes playfully would share his culture with anyone who showed an interest. Over the years, he held many jobs. He cut cedar shakes, logged and worked at the Welco Lumber Co. mill in Marysville. He spent time as a commercial fisherman and maintained tribal properties. It was in the latter capacity that he spent considerable time tending the needs of the tribes’ two cemeteries, pushing a lawn mower among the headstones and thinking of ways to honor the dead.

He’d also head up to the mountains to clear and clean up around the graves of his ancestors.

Ray Moses was the oldest of 11 children. He was born Feb. 20, 1930, and attended school in Darrington before the family moved to Tulalip. In his junior year at Marysville High School, he joined the National Guard. In 1950, when he was 20, he enlisted in the Army. He was shipped off to the front lines in Korea. He received several medals, including the Purple Heart after being wounded twice.

Decades later, an Air Force pilot during the war tracked down Moses. He had helped save the pilot while enemy soldiers closed in after his plane crashed along the Korean Peninsula.

Moses also was credited with saving lives during a confrontation with Chinese soldiers. Moses sensed they were near and told a superior. After the fighting, he was asked how he knew what others didn’t. The frogs in the rice paddies had stopped croaking, he told him.

“Indian time is about paying attention to the world around you,” he once said. “It’s about seeing the signs of the world and being ready when it is time to do what you need to do. That may be gathering or harvesting or it may be spiritual work, but no matter what you are doing, when you are engaged in something, you have a duty to give it your full attention.”

Moses often credited his grandparents from Darrington and others in his family who’d come to see him before he departed for war. Johanna Moses, roughly 14 at the time, remembers looking out a window as they danced around him in an act they hoped would keep him safe. Until the end of his life, Moses was convinced they had done just that.

“He always said, ‘That’s what protected me,’ ” his sister said.

Moses lived with the flashbacks and nightmares of war, including the death of his brother. Sometimes Johanna was called to help him through. Pfc. Walter Moses Jr. was in his senior year at Marysville High School when he joined the Army to defend his country. He left for Korea on March 10, 1953, and was killed in action less than three months later.

Ray Moses once told of his brother’s last moments in an interview with the tribal newspaper.

“My brother Walter was wounded right next to me. The men carried him to a trench where all the other guys were wounded, 19 of them. Then I heard a big shell coming in. I knew all those guys were killed.”

There was no time to mourn and no choice to do anything but keep fighting.

Months before his own death more than six decades later, Ray Moses still shed tears for his brother.

Ray Moses chose to be buried in the Priest Point cemetery near his mother and brother. It is a scenic spot overlooking the bay. Johanna Moses takes solace in the sun that shone over the service on the grounds her brother knew so well.

“That’s where he wanted to be,” she said.

Eric Stevick: 425-339-3446; stevick@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.