By Louise Lindgren / perspectivepast@gmail.com

In this month of March, designated nationally as Women’s History Month, I’m highlighting two women who deserve to be known for their indomitable spirits and embrace of an adventurous life.

Garda Fogg hiked and climbed in the Cascade Range in the early part of the 20th century. Later in her life she became known as the unofficial mayor of Monte Cristo, having a summer cabin and much influence in that nearly abandoned mining town.

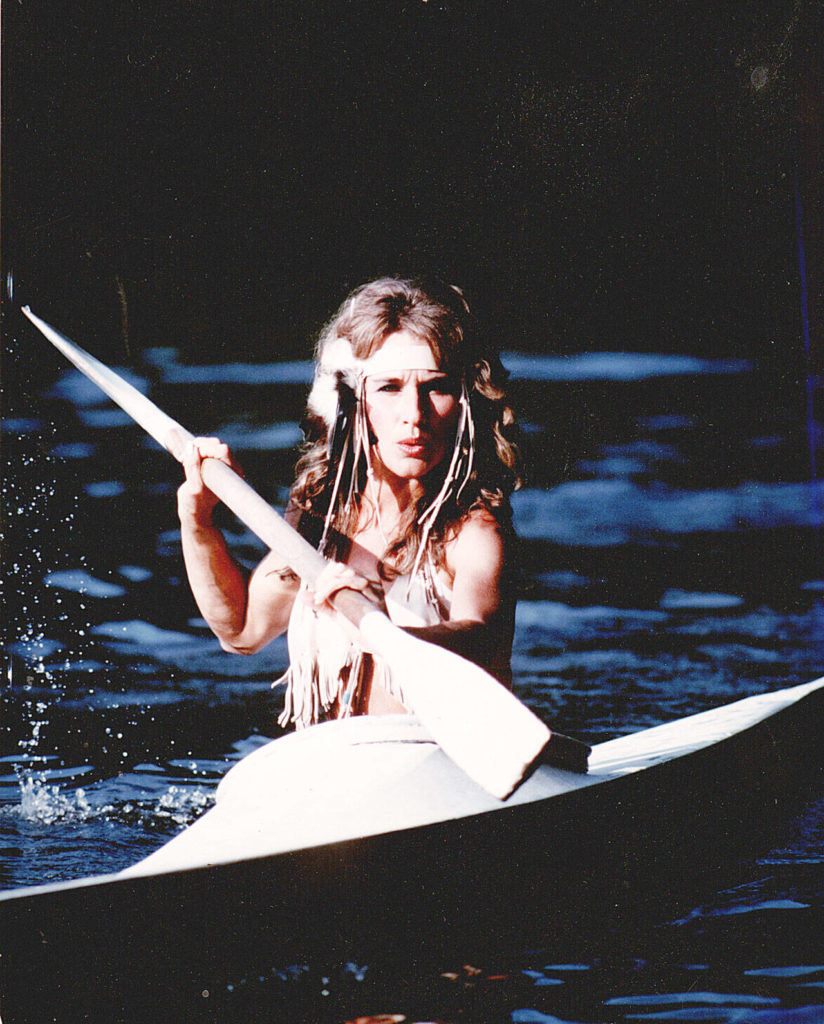

Courtney Bell came here after a 1963 kayak trip from Lake Champlain in Canada to the Gulf of Mexico with her friend, Chris Cunningham. Their partnership ended, Courtney took up residence for a while in an abandoned cabin in Monte Cristo. Not long after that, she met her future husband, Buck Wilhite, and lived with him for two years at that beautiful townsite at the headwaters of the South Fork Sauk River, surrounded by mountain peaks over 5,000 feet tall.

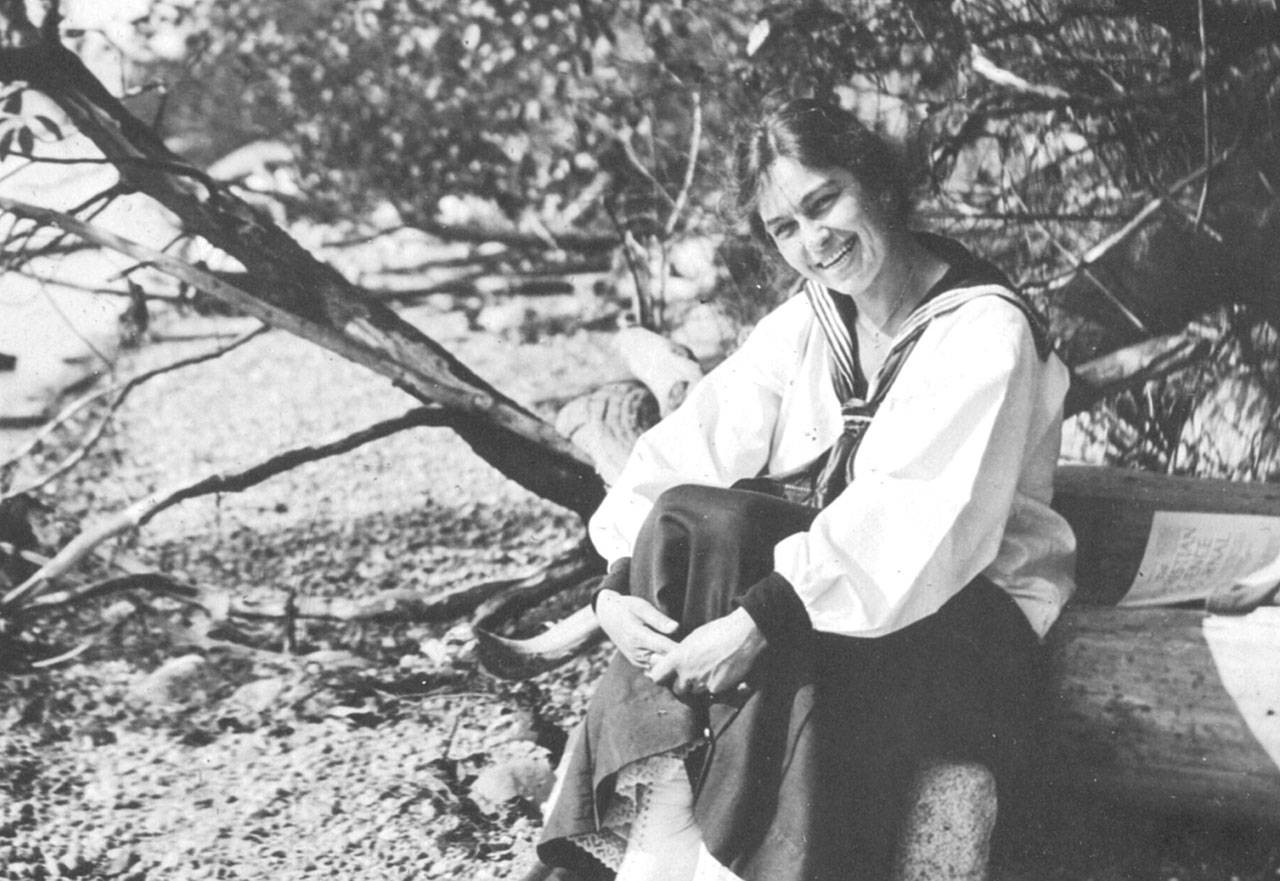

A generation apart, and never knowing one another, these women came to love Monte Cristo and experienced that place through lenses tinted with the colors of their varied pasts. Garda was a stenographer in Tacoma, unmarried, and living with her mother until that lady’s death in 1939. She joined the Mountaineers and saved photos from 1913 to 1919 of her participation in that organization’s outings and climbs. Her adventures were with numerous friends and on highly organized expeditions of those early days.

Courtney was a professional model in her youth, thoroughly enjoyed kayaking, and developed into an artist and professional Celtic harpist. She seemed happiest in the mountains alone or with Buck and sometimes a few close friends. The years she spent at Monte Cristo became etched into her memory so deeply that she was able to put pen to paper and write a small book about her experience. She died of cancer in December 2015 with her book left to me to edit and publish with proceeds going to the Monte Cristo Preservation Association.

If only Garda had left such a document, it would have told of the joys and hardships of those early Mountaineers’ climbs from a woman’s point of view, including how difficult it was to be on the kitchen crew, cooking for groups ranging at times from 20-50 people on the longer treks. She would have mentioned washing clothes in cold mountain streams as noted in a photo album entry of July 31, 1919 at Mount Rainier: “We came across the glacier and have a camp here near the (Paradise) Inn. Not as tired as on wash day.”

Courtney put a chapter titled “Laundry Day” in her Monte Cristo book, telling of the joy she took in that necessary task: “I looked forward to wash day. I loved the scent of the soap, the bubbles and feeling of the hot sudsy water. It was a sense of accomplishment and a completely enriching experience. When I did the laundry I would purposely wear a long skirt and a white blouse. My reason for that was to feel as though I had stepped back in time to the days of a pioneer woman.” Of course, she could heat water on a wood stove in her cabin, not have to scrub clothes with lye soap on boulders in cold creeks as did Garda.

Garda, living an office life during the week, looked forward with relish to the train rides that would take her and others to drop-off points for various hikes from Pierce to Snohomish counties. She noted one hike of 1917, begun via the Milwaukee railroad route through Cherry Valley south of Monroe, where she “climbed 1,200 ft. in ¾ hr. on walk to Lake Fontal through heavy timber.” Other outings put her on the Mount Seattle climb in the Olympics (1913), beginning at Taholah and trekking up rough trail by the Elwha River; Snoqualmie Lodge (Christmas, 1914), Lake Cushman (1915); Deception Pass (1916); and Wallace Falls, Index, Heybrook Ridge (1917).

Courtney’s transportation back to Monte Cristo after her husband Buck died consisted of a small sedan in which she packed everything she needed to weather a week or more of car camping. She had gone from living in the small cabin at Monte Cristo to a large home built by hand with Buck in Republic, Washington, where they spent many joyful years making and selling Celtic harps. Once he was gone, she wanted to go back to some sort of rustic shelter near their first home, and she would build it herself. Her drive to accomplish that was interrupted by cancer, but even with that disease taking its final toll, her car for self-sufficient living remained packed against the day when she could return to the mountains.

Both women lived life unafraid of breaking the rules. Garda was sometimes chastised by her friends for being a bit “wild,” as evidenced by the beach scene where she cavorts in a grass skirt. She celebrated New Year’s Eve 1915 in the large hotel at Scenic near what is now the beginning of the 8-mile tunnel through Stevens Pass, making a note that one of the party participants was the German consul, whom she called “a sport,” and that the state was going dry on Jan. 1, 1916. It’s clear from other entries that Prohibition was not high on her list of necessary regulations.

Courtney’s independence grew over many years to a point where she would not suffer fools at all, having respect only for those who showed that they recognized and honored her strength and ability. Any unwitting hospital nurse who called her “dear” or “honey” would have her ears burned in a minute.

Both women were drawn to the mountains, to rushing waters, to rugged crags and long hikes through dense forests. Perhaps Courtney expresses it best in her book: “One day I walked into the wilderness and it called to me with no hesitation. What I found there was a solution to every facet of my life that needed a new and positive beginning. A kind of super energy was present and it flowed into me from every direction … We must enjoy the journey, not tripping to failure on the rocks, as they teach us and allow us to step beyond.”

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.