SILVANA — On the last day of his life, he wore a black pair of Winthrop dress shoes, a dark suit jacket and a leather belt with letters on the buckle, G-R-N.

If those were his initials, his name has been like an unsolved crossword puzzle for four decades.

Spencer Fuentes was a teenager July 23, 1980, when he found a body while fly-fishing the Stillaguamish River, where the water forks at the east edge of Silvana. Fuentes caught the smell early that afternoon north of the family farm. He thought it was a dead animal.

Something was hung up on a logjam a half-mile northwest of the I-5 bridge, in a channel that has since shifted. It was hot. The river was running low, ankle-deep in places. Fuentes looked closer. He saw the man’s arms and tattered clothes being tugged downstream.

He still has a clear picture of it in his mind, he said Thursday.

Fuentes ran to a neighbor who called police. A sheriff’s deputy was skeptical. No one had been reported missing in or near the river. The deputy did not want to ford the water. They drove together to the other side. The deputy huffed across sand and gravel.

“It took him about five seconds,” Fuentes said.

The deputy came back and said, “Yeah, that’s a body.”

Today hazelnuts and blueberries bloom at the farm along the Stillaguamish, about 10 miles short of Puget Sound by the river’s lazy current to the delta. On the opposite bank is a somewhat new tribal department of natural resources.

In the 1970s, a federal court reaffirmed tribal fishing rights in the landmark Boldt decision. Gill-netting tribal fishermen were a common sight at the time, Fuentes recalled. The Stillaguamish cuts through the ancestral lands of its namesake tribe. Surviving members gained federal recognition in 1979. The Tulalip Indian Reservation sits five miles south of Silvana.

Whether the man belonged to a Coast Salish tribe is uncertain. But it seems likely he had indigenous heritage, according to a 2018 report by state forensic anthropologist Dr. Kathy Taylor.

This month a lab finally extracted his DNA, to look for a potential match in the federal database CODIS.

The man is one of over a dozen unidentified people whose remains have been found in Snohomish County since the 1970s.

These cases have been granted renewed hope in the past year or so, with advances in technology. Genealogists have been working with detectives to compare DNA evidence with data on public ancestry sites. Coupled with old-fashioned research, a skilled genealogist can build a family tree to identify a person, if first, second or third cousins have entered their genetic profiles into an open database, like GEDmatch.

Genetic genealogy led to a breakthrough arrest last year in Snohomish County, in the killings of a Canadian couple from 1987.

Soon the same technology could help give names to Jane and John Does.

For the man in the Stillaguamish, there’s a catch. To build a genetic family tree, you need to be able to compare genes. Ancestry databases have massive pools of DNA from people with European roots. Not as many American Indians use the sites.

Some genealogists have been encouraging native people to submit their DNA, to help solve these cases and family mysteries.

“We want to be able to return their bodies to their tribes,” Snohomish County cold case detective Jim Scharf said.

So far it has been a tough sell.

Stilly Doe

His hair was graying.

Stubble peppered his boxy jawline.

He used arch supports made of paper, leather and metal. He had a hammer toe deformity on his left big toe. His teeth were in bad shape.

The man, nicknamed Stilly Doe, would’ve stood about 5-foot-6 and weighed around 150 pounds, according to the Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office.

His age was difficult to narrow down. He could’ve been in his 30s or his 70s.

An autopsy found a possible cause of death: coronary artery disease. The arteries that carried blood to his heart were hardened and narrowed. It’s common among the elderly and those with diabetes, high blood pressure or chronic alcohol problems, according to the National Institute on Aging.

There were no signs of trauma. Officially, how he died is undetermined. He had no water in his lungs, but drowning wasn’t ruled out.

The week he was found, the temperature touched 84 degrees in Seattle. But he was not dressed for a dip on a hot day. He wore upper and lower long underwear beneath a long-sleeve red flannel shirt and dark cotton pants.

The body’s condition suggested he’d been dead for months. He could’ve fallen in while fishing. Or he could have ended up in the river for any reason.

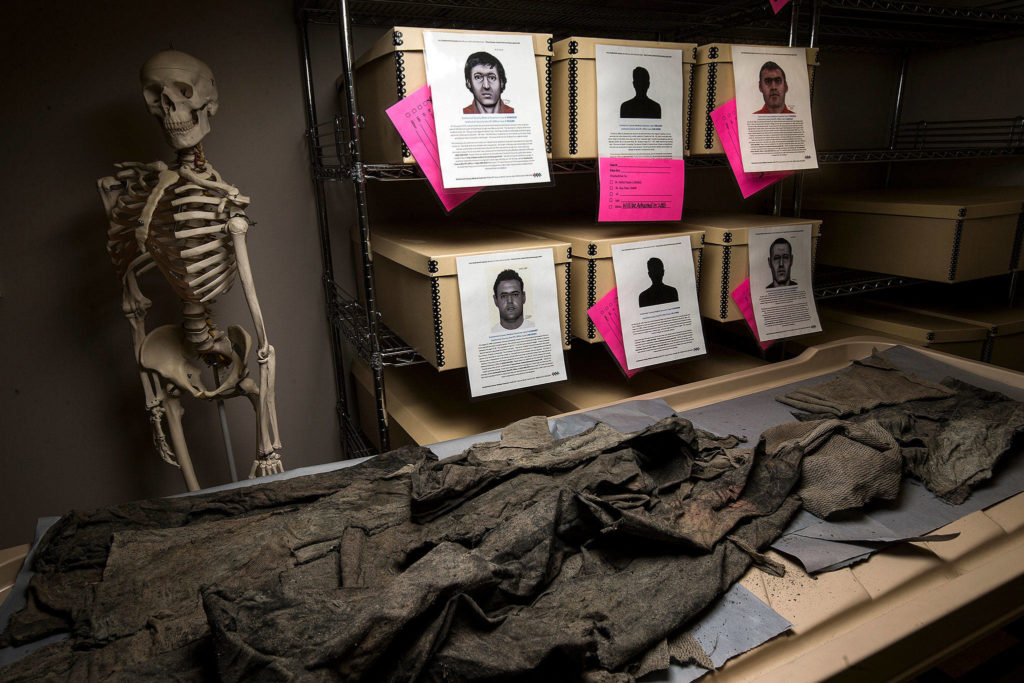

His grave was exhumed at the Arlington Municipal Cemetery in late 2017, to recover his bones and possibly his DNA.

Forensic artist Natalie Murry, a former Kent police officer, reconstructed his face based on the skull in April 2018. Brought to life, he had a broad strong chin, bushy brows and dark features. The shape of his eye sockets suggested a kind of sleepy gaze, Murry said. Some traits like hairstyle and skin tone are educated guesses.

Murry gave him stubble and a red shirt.

Water seeped into his grave in rainy seasons. In summer it dried.

Thirty-seven years of wet, to dry, to wet, to dry can degrade DNA. Bone was sent to a lab in North Texas last year. The lab notified local investigators March 6 that the man’s DNA had been extracted.

If there’s a match in the database, it won’t be found instantly.

Detectives keep looking at other clues. Stilly Doe had been buried with his clothing.

The 40-inch leather belt didn’t go into the tomb. No pictures of it survived in records. So we don’t know if, say, the middle letter of the buckle was a larger monogram. It’s possible the letters could be a red herring — an old knock-off brand, or a factory code, or someone else’s custom belt picked up for cheap at a thrift store.

Or it’s possible his name has been there all along, in the blanks between G___ R___ N___.

The gene pool

Junel Davidson first delved into genealogy two decades ago to solve a mystery in her family, about a grandfather who abandoned a marriage, changed his name and didn’t tell his new family. She’s writing a book about it. Now in Salinas, California, she helps to track down relatives of people who died with no kids, siblings or will.

Davidson, 71, was born in Snohomish. She’s a member of the Shoalwater Bay Tribe southwest of Aberdeen.

She visits her home state in summer.

She has worked with Barbara Rae-Venter, a retired California lawyer whose genealogy research led to an arrest in the Golden State Killer case. Rae-Venter has been helping Snohomish County detectives to try to identify a young victim in a 1977 murder.

Last year Davidson came to Washington with 17 DNA kits that her genealogy group bought in a Father’s Day sale. She gave out the kits for free at talks on the Tulalip reservation. Part of her goal was to help solve cases like Stilly Doe or the Spencer Island Doe, both cases where the deceased is believed to be native.

Few Pacific Northwest tribal members are in public genetic databases. The American Indian DNA Project has mapped the oldest known paternal ancestors for hundreds of people with native heritage. Most are clustered on the East Coast. Only two are within 500 miles of Snohomish County.

Over 15 million people have taken a consumer DNA test, according to research published in November in Science magazine. Hundreds of thousands have transferred data to public third-party sites, the kind that detectives can comb through.

Last year about 60 percent of people with European heritage would find matches at the third-cousin level or closer, on a site like GEDmatch. That’s the bare minimum to start building a tree.

As sample sizes grow in the near future “virtually any European-descent U.S. person” could be identified by genetic genealogy, the study found.

Most people don’t pay $100 for tests because they want to provide evidence in a cold case. They want to know about their family and themselves. One selling point is that tests can tell people, roughly, the regions their ancestors came from. This is done by comparing with the genes of people who are already in the system.

So for non-whites, the tests aren’t as effective.

“It creates a bit of a catch-22,” reads a story by the radio program Marketplace in 2018. “To improve its product, (a genealogy site) needs more people of color to buy its kits, but people of color won’t buy them if they don’t provide worthwhile information.”

Davidson has seen an extra layer of distrust of DNA tests among Native Americans. She traces some of the wariness to the history of blood quantum laws, where the U.S. government defined who could receive tribal benefits based on the fraction of their “Indian blood.”

On the Tulalip reservation, Davidson was asked if the tests could be used for disenrollments. DNA can be strong evidence that two people are related, but no single test can prove a person is from a specific tribe, according to the National Congress of American Indians.

There’s also an infamous story from Arizona. Genetic samples collected from Havasupai tribal members in 1990 were meant to be used to study diabetes, but researchers used blood samples to study other things like geographic origins that contradicted tribal traditions, according to the New York Times.

Still, Davidson hopes more native people will try the tests, to better know their family histories. And she’s open to letting law enforcement use her own DNA, if it helps to bring answers to other families who have been missing a loved one.

On the reservation, she gave out all 17 kits.

She hasn’t heard if any were mailed in.

Tips about the Stillaguamish River John Doe can be directed to the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office at 425-388-3845.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.