Like most of us, Beverly Bowers can’t drive through Everett without seeing people who are homeless, people whose possessions all fit in dirty backpacks or shopping carts.

Bowers, who wears a heart pendant with a heart-shaped hole in it, reacts personally to the misery and squalor she sees on the streets. She looks more closely than most of us do. She is looking for her son.

The other day, she saw him walking down Everett’s Rucker Avenue. His hair was shaggy. His baggy clothes were filthy. He had no shoes.

“I’ve lost my son,” the 63-year-old Everett woman said.

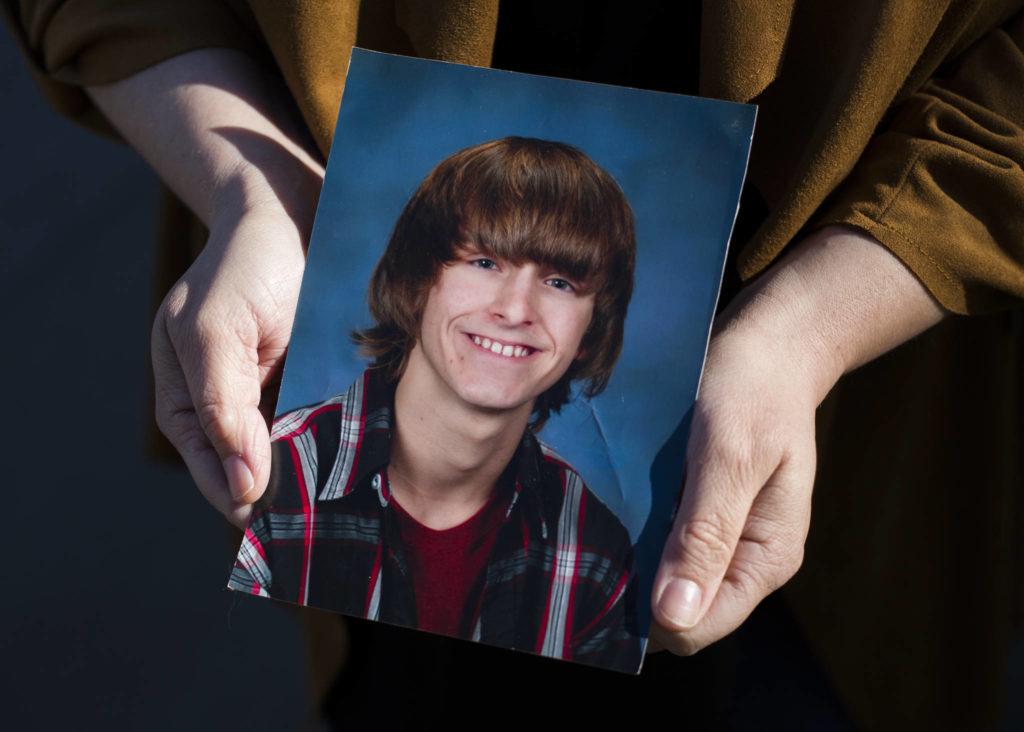

Now 25, her son began displaying signs of mental illness around age 18, she said. Bowers and her daughter, Lea Alejandro, the young man’s older sister, sat down Thursday to share their heartbreak.

Around the time he graduated from Marysville Arts & Technology High School in 2014, they said, he seemed to lose interest in life. “You’d talk to him, he was not there, not present, he was detaching,” said Alejandro, now 42.

His mother recalled the chilling time he was found sitting on his bedroom floor talking to himself in a bizarre way. His sister said he would become transfixed by his image in a mirror.

An extremely disturbing incident, the killing of a kitten, led to him being kicked out of Bowers’ Everett home. She called police, they said, and he was taken to the Snohomish County Triage Center at the Compass Health facility on Broadway. That first time, he spent two weeks at Compass Health.

After many stays in behavioral health facilities, brushes with the law, family members paying to rent him a room, and noncompliance in taking needed medications, Bowers’ son has been “officially homeless” since 2017, she and Alejandro said. His charges include criminal trespass and being in possession of a concealed weapon, a knife.

Alejandro said she and her husband have made use of Everett’s municipal trespass ordinance, which helps in calling police. Yet her brother has repeatedly shown up at their home, where they are raising two young daughters. He has urinated on their back door and slept under her husband’s truck, she said.

Their house was once her grandmother’s home. Her brother had been allowed to stay there, in the basement, before his grandmother died, and mother and daughter believe he still thinks of it as a home base.

“It’s not for the lack of us trying to get him treatment,” Alejandro said. Her brother, she said, “self-medicates” and has used methamphetamine and hallucinogenic mushrooms. “There’s nothing more we can do to help him. It’s his own free will.”

When she does happen to see her brother, she’ll give him a protein bar and some water — but never cash, which could lead to an overdose.

His school days gave little hint of what was to come. He attended Jackson Elementary School in Everett and was a wrestler at Marysville Middle School. As a senior project while at Marysville Arts & Tech, he and a friend conducted a pet food drive.

Yet the many jobs he had, at a car wash and in retail, were short-lived, they said.

His parents had split up, and his father later died of cancer, Bowers said. She works as a contract security guard at the Snohomish County PUD. She monitors surveillance cameras, and during night shifts sometimes has to shoo away others found sleeping on PUD property.

Bowers has mixed feelings about the “no-sit, no-lie” ordinance approved in March by the Everett City Council. Not scheduled to take effect until a pallet shelter project is completed behind the Everett Gospel Mission, the ordinance would ban sitting or lying on sidewalks in a 10-block area east of Broadway, between 41st Street and Pacific Avenue.

“I totally understand the businesses,” she said, but when people get meals outside at the mission “where are they going to eat?”

“I want my son to be able to go and sit someplace, not behind some bush, but out and visible. He would be less vulnerable,” Bowers said.

At times, she said, her son has had a roof over his head. He has stayed at the Everett Gospel Mission and at the Lighthouse Mission in Bellingham. She once got a call to pick him up in Bellingham, but by the time she arrived he had left the shelter.

Alejandro said she and her husband paid to rent him a room in central Everett. But he soon disappeared, leaving all his belongings.

He’s had professional help, including stays at Compass Health, in a Fairfax Behavioral Health unit at Providence Regional Medical Center Everett’s Pacific campus, and at Smokey Point Behavioral Health Hospital. And through a local nonprofit, the Hand Up Project, he was housed from last December to early March at a motel near the Everett Mall.

When he did have treatment plans and medications, “he wouldn’t do it,” Alejandro said.

Grateful for what help her son has had, Bowers remains frustrated at how difficult it’s been to find resources.

Today, they have a glimmer of hope. With the help of a Catholic Community Services navigator, Bowers said her son has applied for and received Social Security disability benefits.

They’re hopeful he may soon qualify for a studio apartment near downtown Everett as Compass Health prepares to open a new building. It’s just off Broadway on the corner of Lombard Avenue and 33rd Street, with 82 units of supportive housing. On Friday, the agency celebrated with a virtual grand opening. The building, which will be coupled with treatment and support services, is phase one of the Compass Health Broadway Campus Redevelopment Project.

In the meantime, a mother and daughter live with fears and sadness. “We’re mourning the living,” Alejandro said.

“My greatest fear is that he’s going to be found dead somewhere,” said Bowers. “I wear this hole-in-the-heart necklace, it’s exactly how I feel.”

Julie Muhlstein: jmuhlstein@heraldnet.com

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.