By The Herald Editorial Board

Recent action by the Biden administration and in the U.S. Senate seeks some overdue changes in how marijuana is addressed by the federal government, especially in how that regulation is applied to Washington state’s own laws that legalized cannabis for retail sale and recreational use a decade ago.

Both moves have been viewed by some as election-year political overtures to “the youth vote,” but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t some sensible justifications for many of the proposed changes.

The Biden administration announced last month that it would move to “reschedule” marijuana, reducing its classification from a narcotic on par with heroin and LSD — with no medical or research value — to one comparable to prescription drugs that include ketamine, Tylenol with codeine and anabolic steroids. This wouldn’t legalize marijuana under federal law but would reduce its classification and treatment from a Schedule I drug to a Schedule III drug and would loosen federal rules, including restrictions that have complicated and limited medical and scientific research of cannabis, its uses and its effects on mental and physical health.

President Biden and Vice President Harris invited criticism of pandering to the “hip kids” with “reefer slang,” noted The Washington Post, by tweeting the proposal at 4:20 p.m. on April 20. The term 4-20 serves as code for marijuana. (That the slang has been around since the 1970s, should tell you something of the age of the “kids” we’re talking about.)

But the seriousness of the proposal was backed up last week by Attorney General Merrick Garland, who’s about as no-nonsense on the subject of drugs as Sgt. Joe Friday of “Dragnet” fame. Garland announced the Department of Justice would seek the rule change, the process for which will include a public comment period and review by a federal judge before taking effect.

Lowering cannabis to Schedule III status would allow marijuana businesses, such as growers, processors and retailers in Washington state to deduct business expenses on federal taxes; would remove past marijuana convictions as a barrier to government employment, federal housing and visas and would make it easier for scientists to obtain, store and study supplies of marijuana, the Washington State Standard reported.

That research is among the more important changes, because it would “translate to more research on the benefits and risks of cannabis for the treatment of medical conditions,” Dr. Andrew Monte, associate director of Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Safety, told NPR.

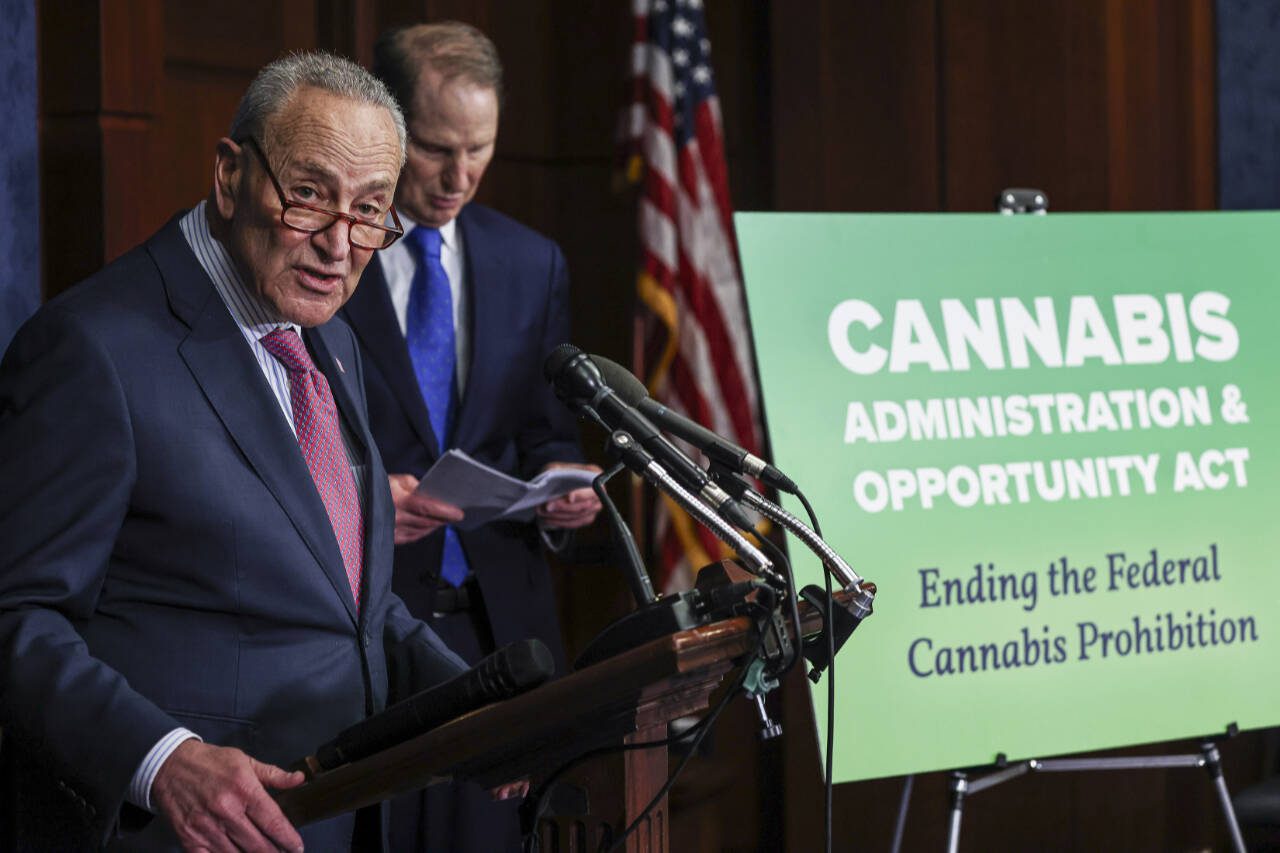

Senate Democrats are now attempting to take those moves even farther with a legislative proposal that would remove cannabis from the list of controlled drugs altogether, legalizing it federally.

In addition to much of what rescheduling the drug to Schedule III would do, the legislation — Senate Bill 4226, the Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act — would shift federal oversight of cannabis from the Drug Enforcement Administration to a federal alcohol and tobacco tax and trade bureau; establish a Center for Cannabis Producers to regulate production, distribution and sale of marijuana products; and instruct the Food and Drug Administration to set labeling standards and create programs to prevent marijuana use among youths.

It’s not clear, however, if the bill would fold in provisions of earlier legislation sought in recent years — the SAFE Banking Act — that would allow cannabis businesses freer access to banking; or if it would just make the issue moot. Because of current federal restrictions, banks even in states where cannabis is legal decline to offer services to marijuana growers, processors and retailers. In Washington state that means up to $1.5 billion in transactions are done on a strictly cash basis, which has left retail operations in particular open to smash-and-grab thefts and robberies.

There are limitations and questions on both proposals that require more consideration and additional provisions.

For example, while reclassifying marijuana would make it easier for researchers to study cannabis, those scientists would still be limited to a few federally licensed providers of marijuana. That could limit the supply for study of the full range of cannabis products, including extracts and edibles, that are now available with much higher potency of THC, cannabis’ psychoactive compound, than leaf marijuana.

Research has been limited but more of it is pointing toward THC’s potentially harmful effects for young people whose brains aren’t fully developed until they are at least 25 years of age.

“It’s just getting worse in terms of the number of kids who are being impacted by cannabis because the potency is so high. We’re now seeing many more mental health issues — schizophrenia, psychosis, depression, anxiety,” Dr. Leslie Walker-Harding of Seattle Children’s told The Seattle Times last December. “I’ve seen it and it’s scary.”

Debate remains on cannabis’ health effects, which is why much more data, research and study are necessary.

And while 17 Senate Democrats, including Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., are backing the recent legislation, the SAFE Banking Act’s multi-year struggle for passage should inform those lawmakers that full legalization of cannabis will be a long battle. Better to take smaller steps toward that goal by focusing efforts on the cannabis banking bill — which had bipartisan support in the Senate near the end of last year — and get it passed first.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.