By The Herald Editorial Board

Two works in progress — both tied to the Northwest rivers that support wildlife and communities in the region — were unveiled recently; one in the Washington state Capitol, the other in the nation’s capital.

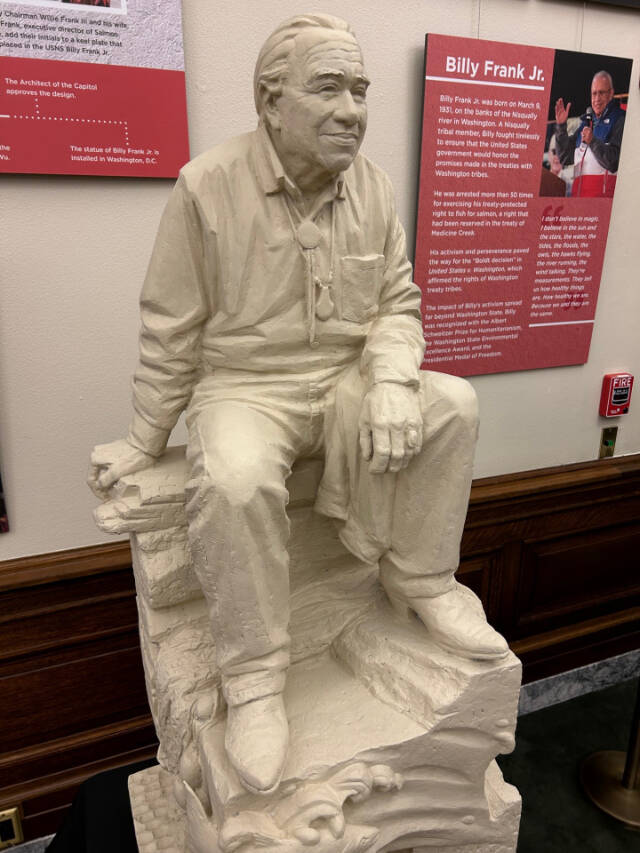

The first is a model of a sculpture to be cast of Billy Frank Jr., the Nisqually tribal leader and Indian fishing rights activist, who helped drive protests and advocacy during the 1960s and 1970s, leading to the 1974 Boldt Decision in a U.S. District Court that cited treaty rights to ensure protection of tribal fishing access and the abundance of fish those treaties guaranteed.

The scale model, which shows Frank seated on a river bank with salmon leaping at the water’s edge beneath his feet, will be used in casting two bronze statues. The maquette, now on display in the lobby of the lieutenant governor’s office at the Capitol, was unveiled at the state Capitol in Olympia in January, revealing the design for two sculptures to be cast in bronze.

Later next year, one of the bronze 9-foot-tall sculptures of Frank will be placed in the National Statuary Hall at the U.S. Capitol, one of two figures representing Washington state in the hall. The second sculpture will be installed at the Legislative Building in Olympia.

The second work in progress was the ratification Friday at the White House of an agreement among four Northwest Native American tribes, the states of Washington and Oregon and the Biden administration that provides a framework and commitments to restore the Columbia River Basin and its tributaries, its salmon and steelhead runs, expansion of the region’s clean energy production and more.

Friday’s signing ratified the Columbia Basin Commitments announced in December, a settlement among the U.S. government, the two states and the tribes — the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon and the Nez Perce Tribe — following years of court challenges over dwindling runs of salmon, steelhead and other fish in the basin.

The agreement suspends litigation by the National Wildlife Federation and the “Six Sovereigns” — the tribes and states — in return for federal commitments to restore the Columbia Basin and assure plentiful fishing in perpetuity, including a promise of at least $1 billion in federal funding and efforts, including a $300 million investment in salmon habitat restoration by the Bonneville Power Administration, which administers the Snake River and other Columbia basin dams. Significantly, much of the money will go toward the expansion of 1 to 3 gigawatts of electricity from tribally managed clean-energy projects, including solar, wind and energy storage.

At the heart of the earlier lawsuits — if not the agreement itself — is the fate of four Washington state hydroelectric dams on the lower Snake River, a tributary of the Columbia, which while producing some of the Northwest’s abundant electrical energy also are responsible for blocking some salmon from their reproductive cycle and threatening the health of fish.

Tribes, environmental groups and others have sought the breaching of the four dams — Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite — as the best chance for restoration of chinook and other salmon runs, steelhead, lamprey and other fish to which treaties have guaranteed tribal access, an outcome among other actions deemed necessary in a 2022 report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Communities in the state’s southeast and others, however, have fought removal of the four dams, pointing to the potential loss of green energy from the four dams, especially as demand increases for non-carbon-emitting energy sources necessary to limit the climate crisis; as well as other services of the dams, including irrigation, barge transportation for agricultural products, flood control and recreation.

Ultimately, Congress would be responsible for deciding the dams’ fate.

Those supporting the dams’ continued operation have expressed skepticism of the Columbia Basin Commitments, because it lays out a path to replace the energy and other services provided by the four dams, replacements that they see as either inadequate or too costly, while some among the agreement’s parties are uneasy that the pact pushes removal of the dams to an indefinite schedule and risks continuing low returns of salmon and perhaps their eventual extinction.

Regardless of the unease on each side, however, the path laid out in the Columbia Basin Commitments must be pursued with full measures, precisely because of the promises made in treaties more than 150 years ago to the tribes and their people in exchange for the lands that the nation and its states now occupy.

Breach of those treaties — in the extinction of salmon and steelhead, and the further erosion of tribal communities and cultures — would be an inexcusable injustice and a loss for all.

It’s timely then that Billy Frank Jr., who helped lead the fight for tribal rights and salmon survival, will soon stand watch to ensure those commitments are kept — in Olympia and Washington, D.C. — from his riverbank post, salmon at his feet.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.