As the school year takes off and the first progress reports trickle in, teachers will ask some parents to have their child evaluated for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, or ADHD. Your child’s teacher may recommend that you make a trip to your pediatrician’s office or see a child psychologist.

What does this mean? Why is your child’s teacher singling him out? Sure, Billy is a busy kid, but does that mean that he has ADHD? What is it, anyway?

Teachers commonly identify students at risk of ADHD. But when children are severely hyperactive, their parents know it from the get-go. They notice their child is “different” than other kids their age — and they can be a handful at home. Constantly fidgety, into everything, racing around, impulsive, distractible and always on the go, these children can tax the patience of Mother Teresa. But that kind of severity may be more the exception than the rule.

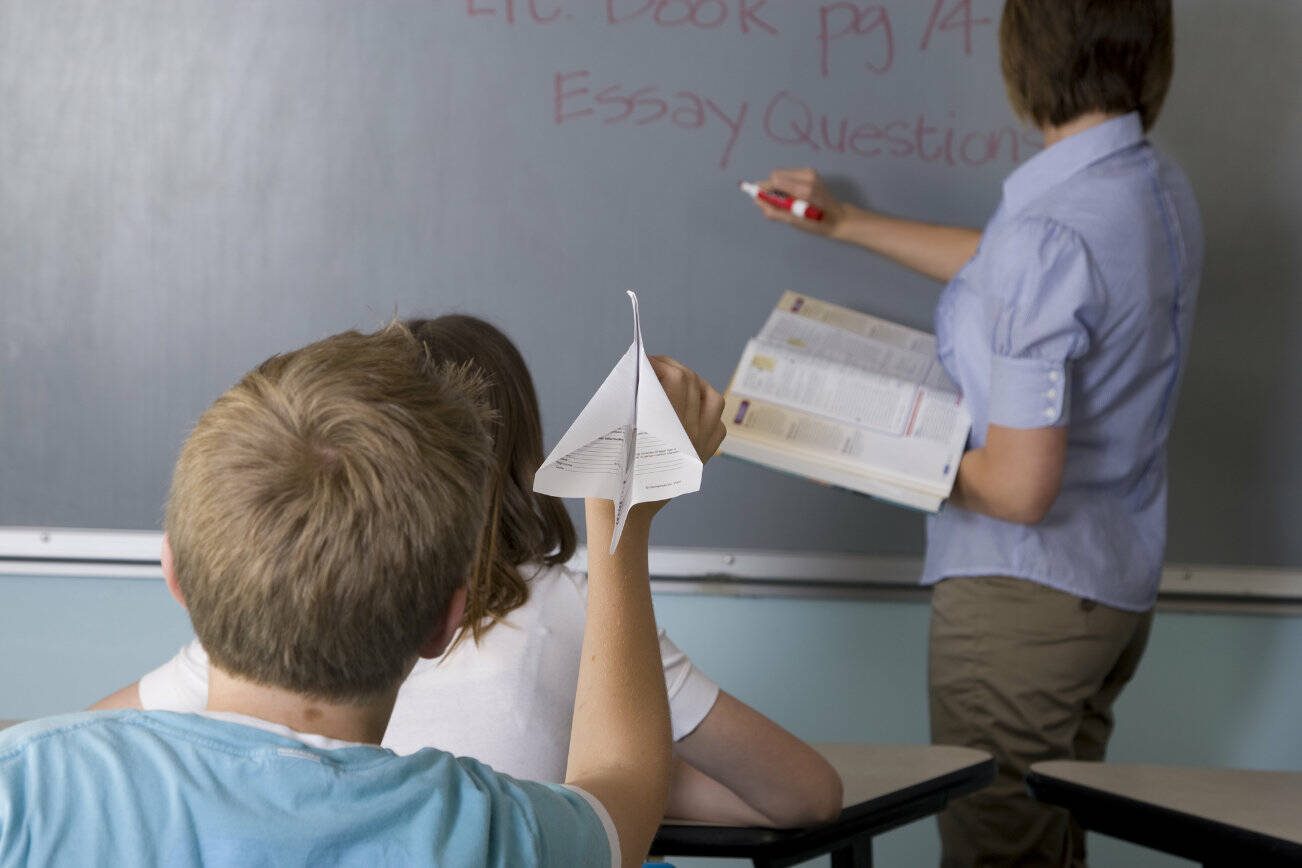

Typically, children are identified as needing academic or behavioral support in third or fourth grade when they are expected to focus for longer periods of time. At this stage, teachers start noticing students whose performance falls outside the range of their peers in terms of behavior or academics. These youngsters show a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity, which may result in them being fidgety and restless, easily distracted, often interrupt the teacher and others, can’t keep their hands to themselves, can’t seem to stay on task, and frequently forget to hand in their homework. Trust me, elementary school teachers have seen thousands of same-age children over many years — they often know who is within the typical range and who isn’t.

Unfortunately, despite advances in brain scanning technology, there are no definitive tests (blood tests, for example) for ADHD. Typically, health care providers collect information from parents and teachers which describe the child’s behavior at home and at school. We use extensive questionnaires that ask parents and teachers to rate their observations of your youngster, and then we look for patterns of behavior which will lead us to a diagnosis. Your pediatrician has to rule out a variety of other medical causes of these behaviors (hearing impairment, for example).

Parents try to understand what this condition really means. They ask me, “Joey’s able to have a laser focus when he is playing his Xbox, but he can never remember to bring out the garbage. I don’t get how he can have outstanding attention for one thing and completely blow off another! Maybe he’s just lazy!”

This common observation reflects the mystery of ADHD. Children (and adults) with this condition can focus very well on high-interest and high-satisfaction tasks. But their brains turn into mush when they are working on low-interest, low-satisfaction, boring tasks. For these duties, they feel like they’re swimming through molasses. They will tell you that their brain just doesn’t seem to work — they’re quickly distracted or exhausted. 1

But don’t all kids and adults have to expend more “mental energy” for low-interest jobs? Yes, of course. It takes more mental gas for me to do paperwork than to talk with a patient. But it’s still relatively easy for me to complete the low-satisfaction tasks of my everyday life without becoming overly distracted or fatigued.

So, don’t panic if your child’s teacher suggests an evaluation. It’s important to identify children with this condition so we can help them succeed in school.

Paul Schoenfeld is a clinical psychologist at The Everett Clinic. His Family Talk blog can be found at www. everettclinic.com/ healthwellness-library.html.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.