3. Aftermath: Infrastructure won’t fare well in a big quake

Published 8:21 pm Monday, May 17, 2021

This is the last of three stories about a little-known geologic fault that could trigger a major earthquake in Snohomish and Island counties.

EVERETT — Even at its outermost reaches, the first vibrations feel like a large train passing a few feet away.

Dinner plates crash to the floor in Port Townsend. Windows shatter in Oak Harbor. Families in Auburn parks feel convulsions under their feet.

At the epicenter in Everett, heavy furniture jitters across the floor. Tremors damage even buildings specifically designed to withstand earthquakes.

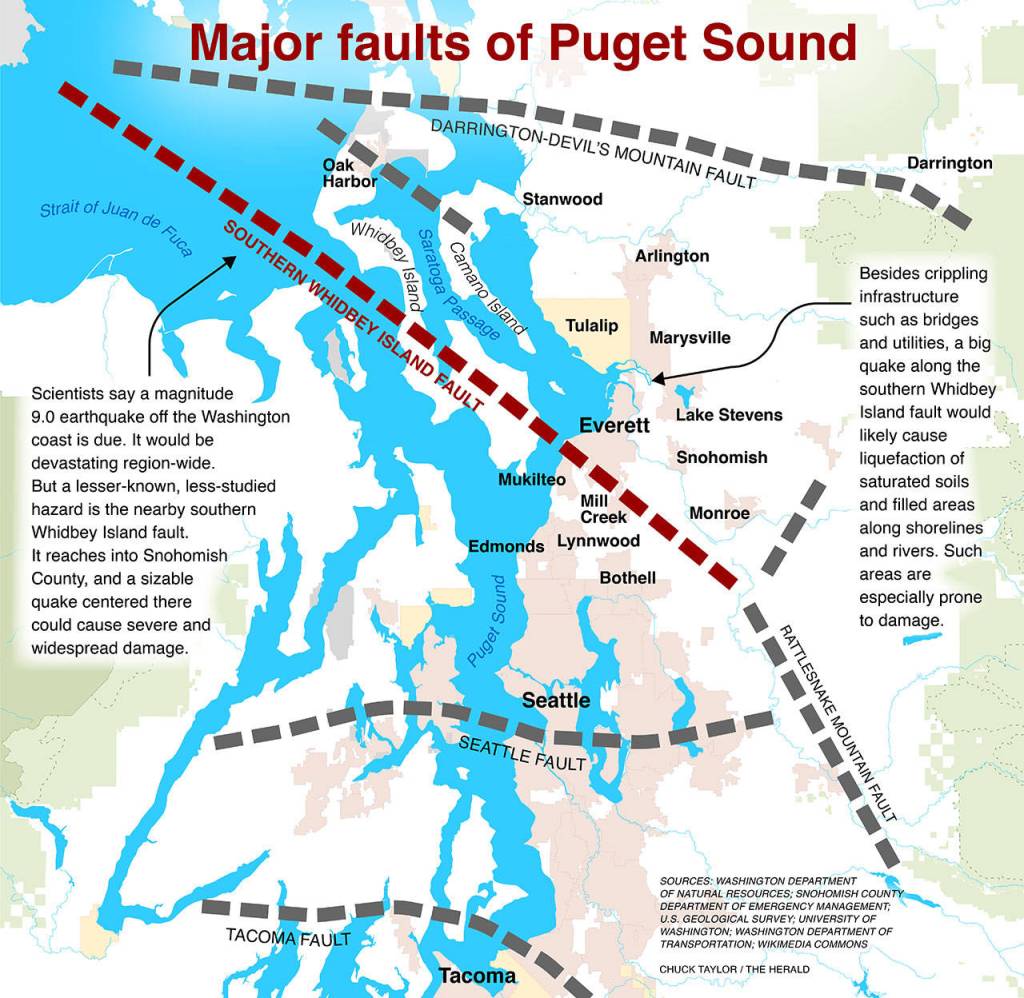

In this Snohomish County training scenario, the southern Whidbey Island fault has shuddered awake with a magnitude 7.4 earthquake.

Within three days, 32 people are confirmed dead, with many more missing. About 2,500 are injured. These numbers will keep climbing. Almost 2,000 residents are in temporary shelters. Teams of residents and first-responders pick apart collapsed buildings in search of survivors.

A residual tremor brings down an apartment building in Mukilteo, leaving another 350 people in need of shelter. A few aftershocks top magnitude 6, finishing off structures weakened by earlier waves. They will continue in flurries every few months for a year.

Both runways at Paine Field Airport look chopped to pieces. Airport workers clear a spot to land supply helicopters. Trains aren’t running. Landslides smother the tracks at Deer Creek in Edmonds and Pigeon Creek near the Port of Everett.

East on U.S. 2, the small cities of Sultan and Gold Bar are cut off from the rest of the world, turned into islands by debris blocking roads. Locals with ATVs establish a relay system to get supplies in and injured people out.

In 47 seconds, the SWIF quake has left damage that will take years to mend. Many schools, older homes and buildings are beyond repair. Mending bridges will take over two years.

So where do you begin?

Marooned

Scientists don’t know when the next southern Whidbey Island fault earthquake will hit. They estimate it battered the region about 2,700 years ago.

Local geologists and disaster experts are intimately familiar with the fault, but it’s not a household name even in the cities it runs near: Port Townsend, Everett and Mukilteo. So there will be panic and confusion.

Let’s say you live in Marysville, but work in Everett. Your child attends Marysville Pilchuck High School. When the southern Whidbey Island fault quake hits, you’re at work. Your kid is at school.

You want to get to your child. But cell phones aren’t working. Landlines are out, too.

Your normal drive home is on Highway 529, but social media shows part of a bridge between Everett and Marysville has crumbled. On your alternate route, I-5, multiple bridges over the river are damaged.

Many of the 800,000 residents in Snohomish County would face a similar plight.

A large population here works farther south, but their kids go to school here, said Jason Biermann, directer of the Snohomish County Department of Emergency Management.

“So how do they reunify?” he said. “How do they find out if everyone is OK?”

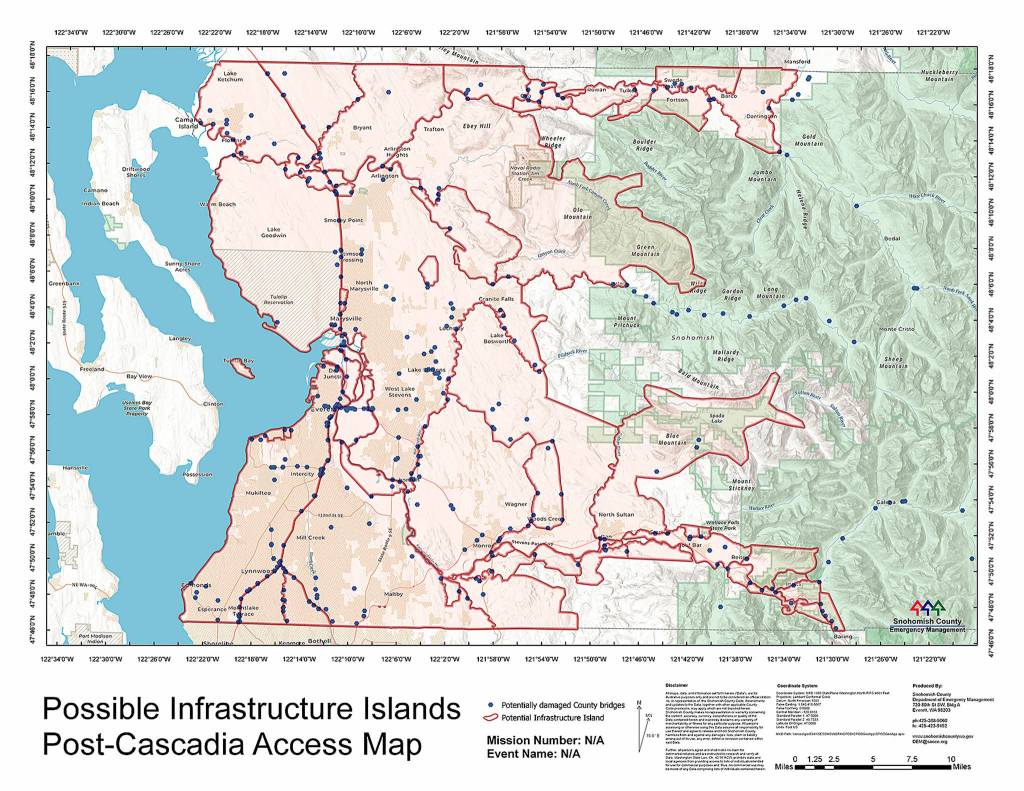

In 2019, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the state Military Department’s Emergency Management Division examined how Washington’s bridges would hold up in a magnitude 9.0 Cascadia quake.

There are 230 state bridges in Snohomish County. Of those, the report predicts just four would escape the Cascadia quake with minor damage — and they are to the east, out of reach of the projected worst shaking.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1615582845175’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; vizElement.style.minWidth=’600px’;vizElement.style.maxWidth=’650px’;vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.minHeight=’667px’;vizElement.style.maxHeight=’887px’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’; var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

About 80% would sustain substantial damage, the report estimated. Some could take 2½ years to repair. Others may need to be rebuilt from scratch.

The southern Whidbey fault is shallow, running right under Snohomish County — as opposed to many miles off shore like the Cascadia fault. If the epicenter is Everett, the SWIF could cause more violent shaking than the fault with greater name recognition. That would mean even more damage to local bridges.

“They might have a pocket around Snohomish County that’s under-calculated for damage,” former county Public Works Director Steve Thomsen said.

The state Department of Transportation spent more than $195 million in the past 20 years to strengthen bridges against earthquakes.

As of late 2019, the department had seismically retrofitted 317 bridges. Another 116 had been partially retrofitted, but required additional work to meet updated standards.

Statewide, another 592 bridges still needed seismic retrofit work.

In addition to the state-owned bridges in Snohomish County, county Public Works inspects and maintains another 200. The department is assessing how those spans could fare in a southern Whidbey fault quake. Public Works plans to use that data to prioritize major thoroughfares and bridges over rivers for reinforcement work. That project is on hold due to the pandemic.

A severe SWIF earthquake would isolate vast regions around the county if bridges aren’t reinforced. There could be upwards of 60 population “islands,” Biermann said. Residents separated from major cities by a damaged bridge could be cut off for weeks.

Those population islands could range from a few square miles — like an oblong patch around Gold Bar — to larger zones encompassing multiple cities.

The greatest risks

Earthquakes themselves don’t kill people.

Collapsing buildings are historically the top cause of death.

Most fatalities happen in large commercial spaces, like Costco, Home Depot and schools.

Any structure not engineered to withstand a SWIF earthquake — essentially anything built before 1975 — poses the greatest danger of collapse. Shaking could cause extensive damage in more than 10,000 buildings in Snohomish County, according to a government projection.

Brick buildings constructed before 1945, known as unreinforced masonry buildings, are vulnerable to seismic waves. Without steel to reinforce load-bearing walls, the exterior breaks away and plummets into the street. What’s left is like the wobbly skeleton of a Jenga tower at the end of a game. Anything still standing will likely give way in an aftershock.

It’s possible to retrofit these buildings to better withstand earthquakes, but it’s expensive enough to deter most building owners. An easy way to spot an unreinforced masonry building is to look for what’s called a header course: lines of bricks with the small short end facing out instead of the long end, making stripes in the otherwise homogeneous pattern of a brick wall.

If you’d like to see some, take a walk in downtown Everett.

[Local earthquakes: Where to learn more and how to prepare]

Of the 313 suspected or confirmed unreinforced masonry buildings in Snohomish County, over 150 are in Everett, with many concentrated downtown, according to a state database created in 2018.

“They’re not going to do well (in an earthquake),” said Mark Murphy, a training coordinator at the county’s Department of Emergency Management. “Period.”

Along Hewitt, many businesses — Taco Del Mar, Everett Comics and the Independent Beer Bar — are housed in what officials believe could be unreinforced masonry buildings.

A building made the list based on three criteria: records showed it was built before 1958; it was made of brick; and it is not a single-family residence. Structures that met some but not all of those stipulations were labeled as “suspected” or “unknown.”

In his role as the Department of Emergency Management’s training program manager, Murphy spends his days reading about the terrible things that can happen in a disaster, like how many people are expected to die, or how many bridges could fail. He uses that information to prepare the department’s staff for the worst. In a magnitude 7.4 SWIF quake, he learned, some of the most at-risk structures house Washington’s youth.

In 2019, the state Department of Natural Resources examined 222 school buildings in 75 school districts. That’s about 5% of the state’s public school buildings.

The department used site inspections and design drawings to estimate damage from a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake. Again, SWIF damage could be even worse in the diagonal band of ribbon-like fissures between Oak Harbor and Bellevue.

The report found most school buildings would be unsafe after a significant quake. About 25% would be beyond repair, and more than 43% posed a high fatality risk. The Marysville and Darrington school districts, as well some Whidbey Island school districts, participated in the study.

Nine Marysville school buildings are considered a high risk, including the main buildings at Liberty Elementary School, Marysville Middle School and Totem Middle School.

Researchers looked at three buildings in Darrington. A 1960s wood shop was considered to be a “high” safety risk and the high school was “moderate-high.” The elementary school, built in 1990, was deemed a low risk.

Index Elementary School has a “very high” safety risk.

South Whidbey’s one building in the study, the 1988 South Whidbey Elementary, was at “low-moderate” risk. Of Coupeville’s six buildings studied, only one was rated at “very high” risk: Coupeville Elementary, built in 1974.

If you’re living in a pre-1970s home, chances are the roof over your head was not designed to withstand a large earthquake.

Craftsman houses, like those in many of North Everett’s neighborhoods, rarely collapse, said Marc Eberhard, a civil engineering professor with the University of Washington.

In most older houses, the building isn’t attached to the foundation. So in the sideways motion of an earthquake, parts of the home can slide off and crack. The basement or crawl space may collapse. Gas pipes could leak. Walls and windows could split.

“There’s a big economic cost,” Eberhard said, “but the likelihood it’ll bring the entire structure down on your head is quite small.”

Life after SWIF

The months after the SWIF quake will reveal a reshaped region.

In the county training scenario, the Everett shoreline has jutted up 20 feet, near the epicenter. Naval station docks are underwater. So is Jetty Island.

The event could cause $9 billion in economic damage to Snohomish and King counties, as well as $1 billion of income loss in Snohomish County alone, according to state and federal agencies.

Hundreds of people could die. Thousands may be injured.

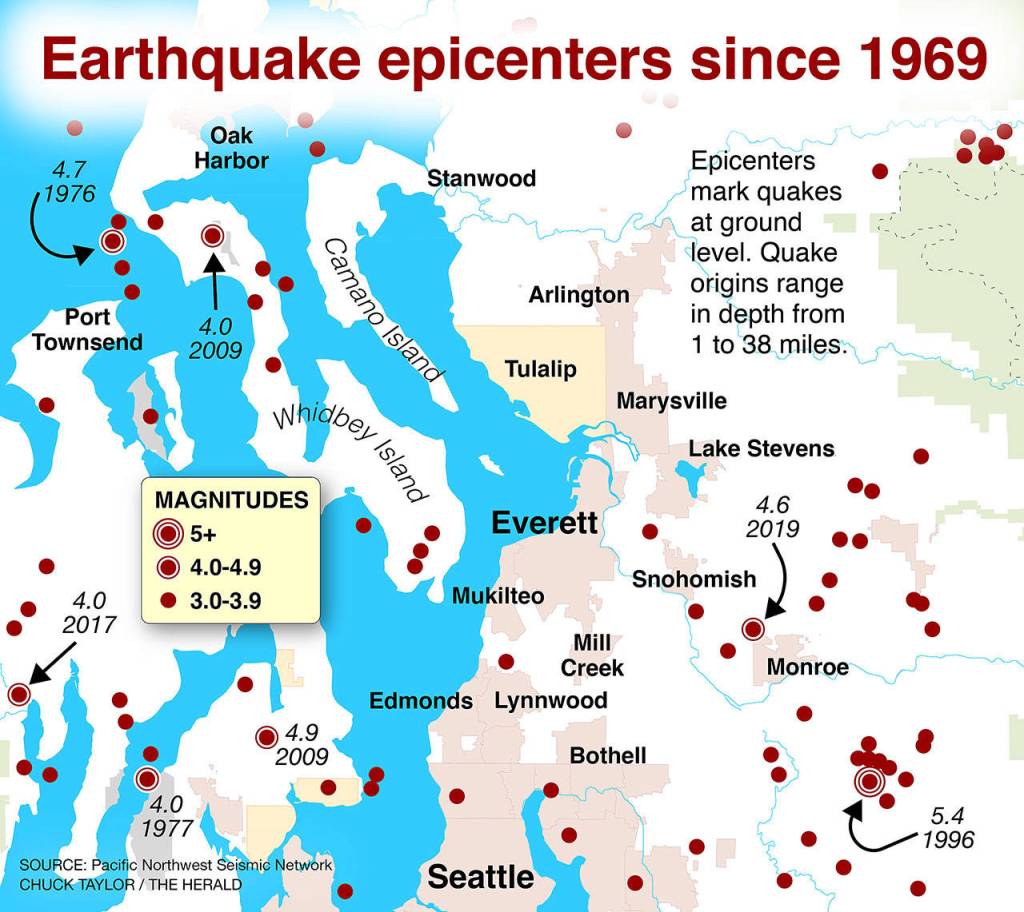

Small earthquakes happen all the time, constantly sprinkling a Pacific Northwest Seismic Network map of Puget Sound with small ripples: magnitude 0.5, 1.7, 2.5, the occasional 4.6, and so on.

Starting in May, Washingtonians should get a heads up of a few precious seconds before any serious shaking begins. The state ShakeAlert system will send out warnings out to cell phones, similar to an AMBER alert.

If a 7.4-magnitude SWIF quake hit tomorrow, Snohomish County residents would not have a reliable water source. Schools would see devastating fatalities. Many roads and bridges would be unusable.

“There’s a lot of work being done to get ready, by a lot of people,” said Biermann, the county’s director of emergency management.

Millions of dollars and years of construction are needed to reinforce Snohomish County’s infrastructure.

So in the meantime, how do we live with a major earthquake looming at some unknown date in the future, not only along the Cascadia fault, but right under our feet?

“Individual preparedness, as basic as that sounds, is sort of the foundation of all of this,” Biermann said.

Everyone should keep two weeks of food and water on hand, plus a way to stay warm and dry, according to disaster experts.

Identify large furniture that may tip over in a quake. Secure it to the floor.

Make sure your water heater is fastened to the wall, and that it has flexible gas and water connectors. If you live in an older home, consider securing your foundation. Know how to shut off your natural gas valves.

If individual people are prepared, they are more likely to help those around them in a disaster. And if we can brace for SWIF, we’ll be all right in Cascadia, said Thomsen, the former Snohomish County Public Works director.

Odds of survival will likely improve with each hour and day.

“If you’re not killed in the quake, you’re probably going to live,” said Murphy, of the county’s emergency department. “Are you going to be inconvenienced? Yes. Are you going to be uncomfortable? Oh, heck yeah.”

Be realistic, he said. Don’t panic.

Julia-Grace Sanders: @sanders_julia on Twitter

Read the rest of this series

1. Buried danger: A slumbering geologic fault beneath us

An earthquake along the southern Whidbey Island fault reshaped the land some 2,700 years ago. Another big one is expected, and it could be devastating. READ MORE

2. Built on pudding: Can modern quake engineering prevail?

At least 30,000 people in Snohomish County live on saturated soils and sediment that will behave like shaken liquid when a big earthquake hits. READ MORE

3. Aftermath: Infrastructure won’t fare well in a big quake

Shockwaves from a shallow fault here could ravage bridges, schools and the water supply in Western Washington. Emergency planners want you to be ready. THIS STORY

A COVID crash course

Ongoing waves of COVID-19 have been, in some ways, like the aftershocks of an earthquake, according to the Snohomish County Department of Emergency Management.

“You have to restart the process every time,” said John Holdsworth, a DEM program manager.

Many lessons of the pandemic could be applied to quake response. One of the most clear messages from the past year? Resources and social services are interdependent. A trucker needs child care to deliver goods to the store for residents to buy.

“All of these systems are intertwined,” Holdsworth said.

The county needs a more efficient way to get food, medicine and social services to hard-to-reach areas, he said. Small towns cut off in an earthquake would need basic resources available on a hyper-local level.

Eventually, as the pandemic fades, the Department of Emergency Management will switch from survival to recovery mode, Holdsworth said. Then staff will spend time analyzing how its emergency response can improve, hopefully before the next disaster strikes.