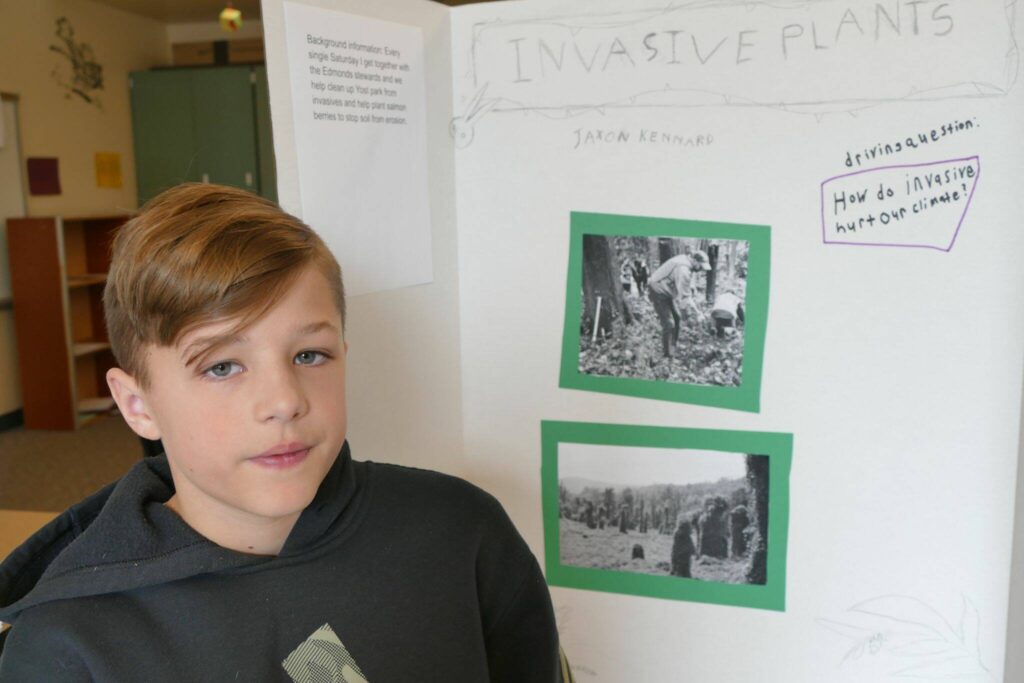

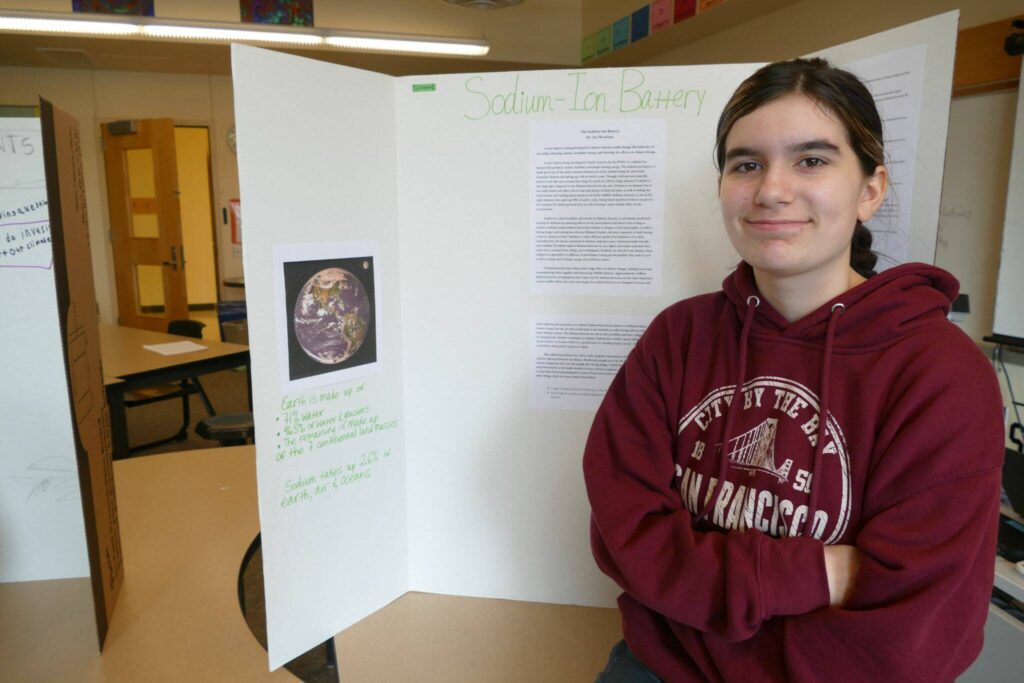

EDMONDS — Jaxon Kennard learned that forests capture planet-warming carbon. So the soft-spoken seventh grader pitched in to remove tree-killing invasive ivy. When classmate Ava Woodsum discovered the high environmental cost of mining lithium for batteries, she researched sodium ion batteries, a potential alternative.

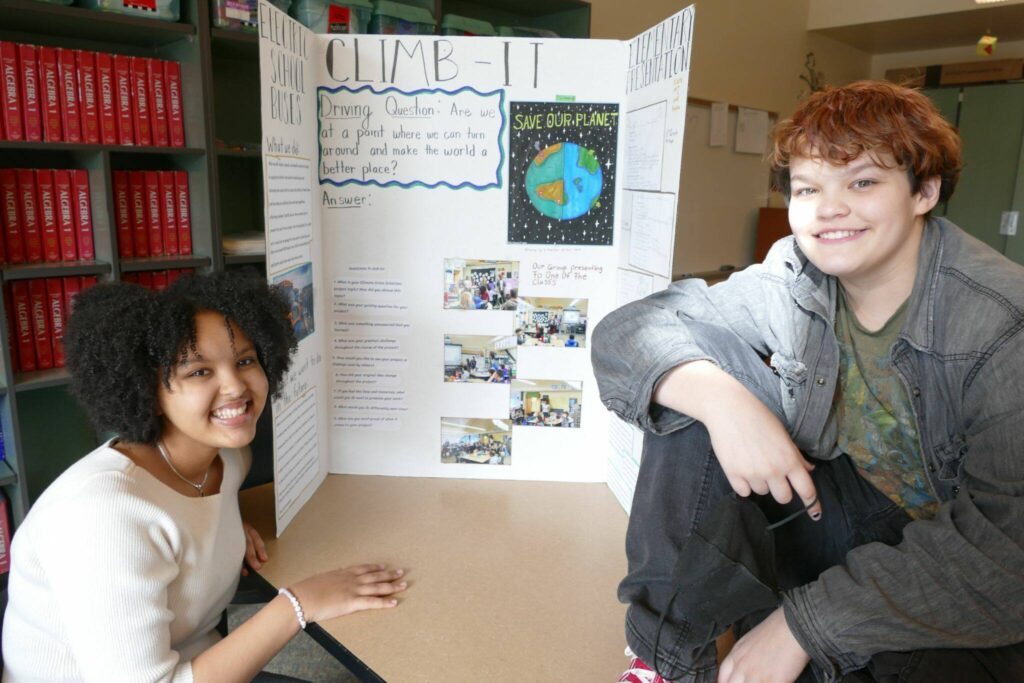

Other middle schoolers in the Climate Crisis Solutions Class at Maplewood Parent Cooperative gave presentations to elementary school kids.

“A lot of them paid attention a lot more than we were expecting,” eighth grader M.J. Pankow said. “They asked interesting questions.”

The elective course these students took during fall semester is taught by Bradley Barton. It has the hallmarks of climate education in Washington state: It is driven by the interests of the teacher. It is multi-disciplinary. The lessons are age-appropriate and in sync with state science standards.

Perhaps most significantly, the Maplewood climate class focuses on solutions right off the bat. The goal is to keep students optimistic in the face of a heavy global challenge. In the words of University of Washington researcher Deb Morrison, “We talk hope forward.”

Morrison has played a key role in a statewide teaching network called ClimeTime. In the past five years, Washington lawmakers have provided $18 million for ClimeTime and related efforts to teach public school students about human-caused climate change. Gov. Jay Inslee is asking for another $10 million this legislative session. As a result, Morrison said, “we’re way ahead of other states” when it comes to climate education.

“We’re probably one of the farthest ahead, … in the top five in the world,” said Morrison, who participates in a United Nations climate education effort.

Washington’s first Climate Education Summit will be held in March. The event has Ellen Ebert, the state’s director of Secondary Content Education, both excited and nervous.

“It will be a place where we can bring folks from across the state, across disciplines and grade levels,” she said. The summit will focus on how different communities are being impacted by climate change, from storm-driven king tides in the west and more brush fires in the east.

Ebert hopes to add a second statewide summit in the next few years, this one for students.

“We want them to have deep understandings of the science and health impacts of climate change, so they can have healthy and productive lives,” she said.

‘Start with knowledge’

Grant funding for climate-focused professional development for teachers is at the heart of ClimeTime. The money, distributed by the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, flows largely through the state’s nine Educational Service Districts. ESDs work with community organizations that offer classes. Some grants go directly to organizations or to Native American tribes. Teachers can also apply for project-based grants.

Before ClimeTime, such teacher training was done by “a coalition of the willing — people whose passion and drive was around protecting the environment would come together,” said Brian MacNevin, regional science coordinator for ESD 189, which includes Snohomish County. Teachers were on their own to research lessons that sync with state Science Learning Standards, which since 2013 have included humans and their relationship to climate.

“Teachers didn’t feel prepared to get involved in climate education. Even if they were, it can be a hot topic in their community,” MacNevin said, acknowledging that atmospheric warming can become a political issue. “As a local control state, we can’t tell any district how they should be approaching it. We can just provide resources.”

In Snohomish County, those resources include ClimeTime-supported courses offered to interested teachers from such nonprofit organizations as IslandWood and EarthGen.

EarthGen has offered climate-related courses to teachers since 2018, program manager Becky Bronstein said. Some teachers are looking for basic information, along the lines of “Climate Change 101,” while others are interested in specific effects, such as changing conditions for shellfish. A summer filled with forest fire smoke inspired a course on the subject.

“Our Climate Justice League is a professional learning community where teachers are with us throughout the year,” Bronstein said. “We start with knowledge, then we want to equip teachers and students to take action on the issue.”

Action can take many forms, Bronstein said, from proposing solar panels for a school to simply finding out which climate concerns community members have.

“We’re learning to do a lot more listening to communities to hear people’s perspectives and opinions,” she said. “As a largely Western Washington organization we wouldn’t go to an Eastern Washington farming community and say, ‘You need to do all these things.’ That wouldn’t land.”

ClimeTime courses are free. In some cases, teachers are paid to attend. They also get professional development credit, known as “clock hours.” But it’s up to them to learn about the courses in the first place. As often happens, Arlington teacher Danene Severson learned from other teachers.

“A lot of teachers don’t know about ClimeTime that there’s a stipend,” she said.

Severson said she didn’t know a lot about climate change before participating in EarthGen’s Climate Justice League, which informs teachers about the changing environment and how it is especially hard on some people, like farm workers facing extreme heat.

She was teaching fifth grade at the time, and climate-related topics that arose in the classroom include Indigenous communities and declining salmon populations. Now, Severson teaches math at Haller Middle School and wonders how she might incorporate what she has learned into her lesson plans.

“We’re talking about ratios now,” she said of her sixth grade class. “Can I talk about the ratio of carbon to oxygen in the air?”

Jennifer Carness, who teaches at Riverview Elementary in Snohomish, is taking a ClimeTime course called All We Can Save. It was recommended to her after she participated in the Climate Justice League.

“I was curious to see if there was a way to incorporate climate justice in elementary education,” Carness said.

One way might be to ask students how they would feel if they couldn’t get outdoors. But she wouldn’t tell her third graders that humans cause climate change — because there is no official curriculum to do so, and because children are easily burdened. State science teaching standards don’t even mention human-caused climate change until sixth grade.

“They have so little control over their world,” Carness said of elementary students. “What we can teach them is what they can control.”

For example, she got students involved with composting and a school garden, projects that got waylaid by the pandemic.

‘Looking at us to solve it’

Barton was teaching science at Maplewood school when the pandemic hit. In spring 2021, he took a ClimeTime online course that inspired him to propose a climate solutions class for middle schoolers, who were old enough to understand the social issues involved. He spent the summer planning it.

The first classes were taught online. Twenty-seven students signed up for the first in-person class in fall 2022. One day they moved into different corners of the room to indicate how they felt about climate change. Angry? Hopeful? Bored? Fearful?

“I mostly felt anger because the older generations did this, but they are looking at us to solve it,” recalled Ava Woodsum. Still, she dove into learning about possible solutions, like sodium ion batteries. She was pleased to report that her dad decided to replace the family’s gas stove after learning from her that its emissions could induce asthma.

Talea Mustefa said she, too, had deep conversations with her father about what she learned.

The girls were among five students who gathered to discuss the class. All were enthusiastic, even if it hadn’t been their first choice as an elective course, and even if they had already learned about climate change. They enjoyed their projects. Talea’s was a beach cleanup, which included disposal of plastics that came from factories that emit greenhouse gases. Maedot Yoseph investigated what it would take to purchase an electric school bus.

Climate class students proudly shared their findings at a showcase event attended by the mayor and school officials. Their teacher is so convinced of the value of student projects that he is applying for a ClimeTime grant that would pay for teacher training in that approach.

Barbara Bromley, who teaches fifth grade at Edmonds’ Hazelwood Elementary, has taken multiple ClimeTime classess, is equally gung ho about student environmental projects. She just received a $3,200 ClimeTime grant to pay for supplies and field trips. It will also pay rent at the Edmonds Theater, where students will present a year-long project on the Salish Sea. One thing they learned was how atmospheric carbon dioxide leads to ocean acidification.

“Kids understand things in relation to climate. They understand way more than we think they can,” Bromley said. Her goal is to get them to think deeply and question sources. “That’s critical, especially in the TikTok world.”

‘Concepts that are going to benefit your life’

Andrea Cartwright, science and engineering director for the Everett School District, noted that the science curriculum is the same districtwide. It is reviewed by committees and the public is given a chance to comment.

“Sometimes the curriculum is really specific on climate change and how that’s human-driven,” Cartright said. “Sometimes it’s more broadly focused on ecosystems.”

Everett teachers are encouraged to localize lessons, Cartwright said. For example, they could use forest fires — which are increasing in number and intensity — to discuss combustion reactions and energy transformations. When last fall’s Bolt Creek fire made headlines and reduced air quality, teachers could help answer a question heard throughout the county: “What’s taking so long to put the fire out?”

The smoke, moderated by Puget Sound breezes, lingered in Everett. It pummeled Darrington. The small town sits in a low-elevation bowl, where airborne particulates from both the Bolt Creek and Suiattle River fires kept students indoors for two weeks. Superintendent Tracy Franke said staff had to reassure anxious children that the fires weren’t close by.

Zacharie Bass used to work in Everett, where district enrollment is 20,434. For eight years, he has been the lone high school science teacher in Darrington, a district with 448 students and and no grant writer. He’d like to see ClimeTime recognize that small districts don’t have the capacity to even apply for resources.

What Bass does have is freedom. He can craft lessons in keeping with his students’ rural environment and his own perspective that climate change is the biggest threat facing humanity. The subject finds its way into chemistry, biology and physical science lessons. Students track seasonal changes in atmospheric carbon. One worked on developing diesel fuel from algae. Another developed a fuel cell from waste products.

“I’m a pragmatic person. How can I teach climate concepts that are going to benefit your life?” Bass said. “We have a greenhouse. Here’s how you raise your own food, have your own garden. How do we make it so people can increase productivity, make money from that and help the earth?”

If students still don’t believe in human-caused climate change, Bass said, he probably couldn’t change their minds.

But these days, he’s less likely to hear the question, “How do we really know the climate is changing?”

Now, he said, it’s, “What if we tried … ?” and “Why don’t we do this?”

Herald reporter Mallory Gruben contributed to this article.

Julie Titone is an Everett writer who can be reached at julietitone@icloud.com. Her stories are supported by The Herald’s Environmental and Climate Reporting Fund.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.