LYNNWOOD — She was 10 when she returned home from Sunday school that cold sunny morning to find her parents and older sister huddled around the radio in the living room of their home in Springer, New Mexico.

It was Dec. 7, 1941. The child studied their grave expressions and turned her attention to the broadcaster’s voice.

“I listened for a moment, trying to catch the gist of what was being said, but it made no sense,” she recalls more than 75 years later. “Something about airplanes and an attack and a place called Hawaii.”

Her father, who fought on the front lines in World War I, the supposed “war to end all wars,” explained to her that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. He understood what his daughter did not. The country was on the brink of entering World War II.

For the next four years, her family consumed every newspaper they could get their hands on, closely following the battles in Europe and the Pacific.

The girl grew up, eloped at 18, moved to Washington, went to college, raised two daughters and spent two decades working as a property insurance underwriter. All the while, she felt a lifelong gratitude to soldiers.

Elaine Noble Reas is 87 now and lives in senior housing in Lynnwood. When her husband died a few months back, she knew it was time to write about the veterans within her family before age catches up with her as well. She understood that she must turn her good intentions into actual prose.

She wrote one essay about her brother-in-law, Herbert Reas, a World War II sailor who survived a Japanese attack on the Bunker Hill aircraft carrier. The offensive killed more than 350, wounded 264 and left 43 missing. Herbert Reas became a professor and dean at Seattle University after the war.

She also told the story of her cousin, Dow G. Bond, who survived the Bataan Death March in the Philippines and three years as a prisoner of war during World War II. When he was called to serve, Bond was 32 with a wife, three young children and a plumbing business in New Mexico. He returned to the Philippines seven times after the war, feeling an affinity for the people who had tried to give what aid they could to the American prisoners.

Reas’ longest piece is about her father, a man who was never effusive with “I love yous” and who seldom talked about the war. And yet today, after reading and rereading the letters he wrote a century ago between World War I battles at the front, she just might know him better than she ever did before.

A different side of dad

William Franklin Noble was 91 when he died Nov. 11, 1979. It was Armistice Day, a date that he most assuredly celebrated as a young soldier in 1918 with other Allied troops. One hundred years ago today, the agreement was signed in the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month that ended fighting in World War I.

When he returned from the war, he’d been told the best thing he could do was try to forget it. That’s largely what he did, settling into life as a husband, businessman and father of three daughters.

In an Albuquerque VA hospital a year before he died, William Noble often quoted lines to his daughter from his favorite poets, Kipling, Tennyson, Service and from “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.” She’d grown up hearing him often quote verses from “The Rubaiyat.” It seemed he had one for every occasion.

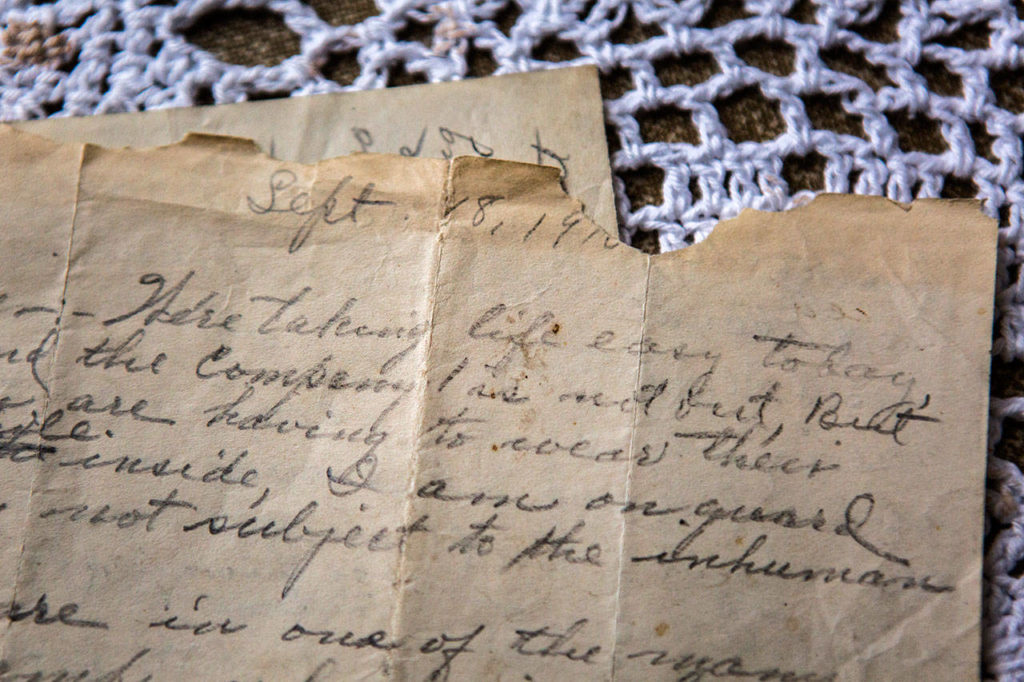

After he died, Reas’s mother gave her a stack of letters and envelopes, which had been written by her dad to his parents during his time in the military, from boot camps in America to the front lines in Europe and during his ascension from private to sergeant.

From the letters and other research, Reas conjures up an image of her father in a foxhole somewhere in the Argonne Forest of France, “cold, hungry and exhausted, the roar deafening as artillery shells screamed overhead.” She imagines a 74-mile march along the Meuse River with him lugging an 84-pound pack through mud often ankle deep, “always wet and cold as the rain fell continuously.” She sees him assembling a two-man pup tent at night, sleeping on soggy ground and eating cold rations. She imagines him in a gas mask stumbling over rough terrain in the dark under heavy fire.

In his penciled cursive, she also discovered a side of her father she did not know, a young man who worried about the farm back home in Oklahoma, who worshipped his mother and was homesick for the company of his family.

His letters took her to the Aisne-Marne, St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne campaigns, and introduced her to the 4th Division, 7th Brigade, 39th Infantry in which he served.

At first, he wrote with bravado after Allied successes, but by August of 1918, after four days of heavy casualties, his tone changed: “I trust the time is not far off until a fair and just peace for all nations is concluded. Surely we will love each other and God more after this is over, for there’s no denying that all nations are being punished severely. We must forget malice and hatred for anyone and work for the welfare of all. May God help us all.”

That September and October brought decisive attacks and a mounting death toll. During the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, his division was in combat for 24 days. It lost 244 officers, and 7,168 enlisted men were killed or wounded.

He wrote his parents: “I look to get home to you folks, just to be with you and love you and be loved. God in his mercy will take care of me.”

He would spend many months in Europe with occupation forces after the fighting ended. For Christmas he asked for tobacco, candy and horseshoes. By April, he was itching to board a ship for home, telling his father: “I’m having a hell of a time trying to think of something to write to you about.”

Today, his letters are preserved in plastic slips in a neatly organized binder.

For Reas, they are revelations.

“I always regretted I hadn’t known him better, but he wasn’t someone who wanted to talk about himself,” she said.

Separate from the story of his war experience, she wrote an essay about the circumstances of his death and words unspoken.

“Many men, indeed, many of either sex, choose never to reveal themselves to those closest to them,” she observed. “They fought their war, then steeled themselves to wall away the horrors they experienced and moved on with their lives.

“They absorbed the blows of economic devastation in the Depression of the 1930s, then picked up the pieces and started again. They married and provided for their families, and whether the marriage was good or bad, they stuck it out. If the dreams of their youth could not be realized, they accepted that as the human condition. And they did very little talking about any of it.

“Generalities are treacherous, of course, but this is the way I think of my father. Perhaps I knew him better than I thought.”

The time had come

Her apartment complex is a sprawling place tucked away among trees well off the arterial that is 164th Street.

In the corridors and commons, residents pass by with acknowledging nods, many using canes and walkers.

The other day, they recognized the veterans among them.

As Reas looked around at the older ones, those who served in World War II and in Korea, she could not help but think that they will soon be gone. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that there are about 496,000 World War II veterans left among the 16 million who served.

She’s glad she wrote about her father, brother-in-law and cousin. She hopes others will find the time to do the same.

“My strongest motivator for trying to get it down is that I have this feeling that too much is being forgotten,” she said. “I just wanted to do my part to preserve a little bit of it.”

Eric Stevick: 425-339-3446; stevick@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.