MILL CREEK — A teacher at Henry M. Jackson High School knew she needed to be tested for the new coronavirus.

In late February, she had frequent close contact with a student who later tested positive for COVID-19.

After a week of trying, she finally got tested on Thursday. It came back negative, but Diane Gorman said the experience shook her faith in how officials are handling the outbreak.

Gorman has a medical condition that weakens her immune system. She started to show symptoms of the virus and went to see her doctor Saturday. She waited two hours, but was sent home without a test.

“I had the student, I had symptoms, it really surprised me,” she said.

Gorman didn’t improve in the next few days, so she reached out again to her doctor, who referred her to a coronavirus hotline. She waited another two hours before speaking with a nurse, who told her she didn’t qualify for testing because she hadn’t been hospitalized with respiratory distress.

She imposed a self-quarantine. Her sickness persisted. She kept pushing to get tested.

“I’m trying to make decisions about life,” Gorman said. “How long can I stay home considering future trips I have planned and et cetera?”

Her primary care doctor refused to see her, saying her symptoms were too risky to bring into the office. So she reached out to her rheumatologist, who X-rayed her for pneumonia. She didn’t have it. She’d been vaccinated for the flu as well. Ultimately it was the rheumatologist who referred Gorman for testing at the University of Washington.

“I knew I was one of the few that was able to be tested,” she said. “I felt even a little guilty.”

When she arrived Thursday, she got a call from the office telling her not to come in to the building.

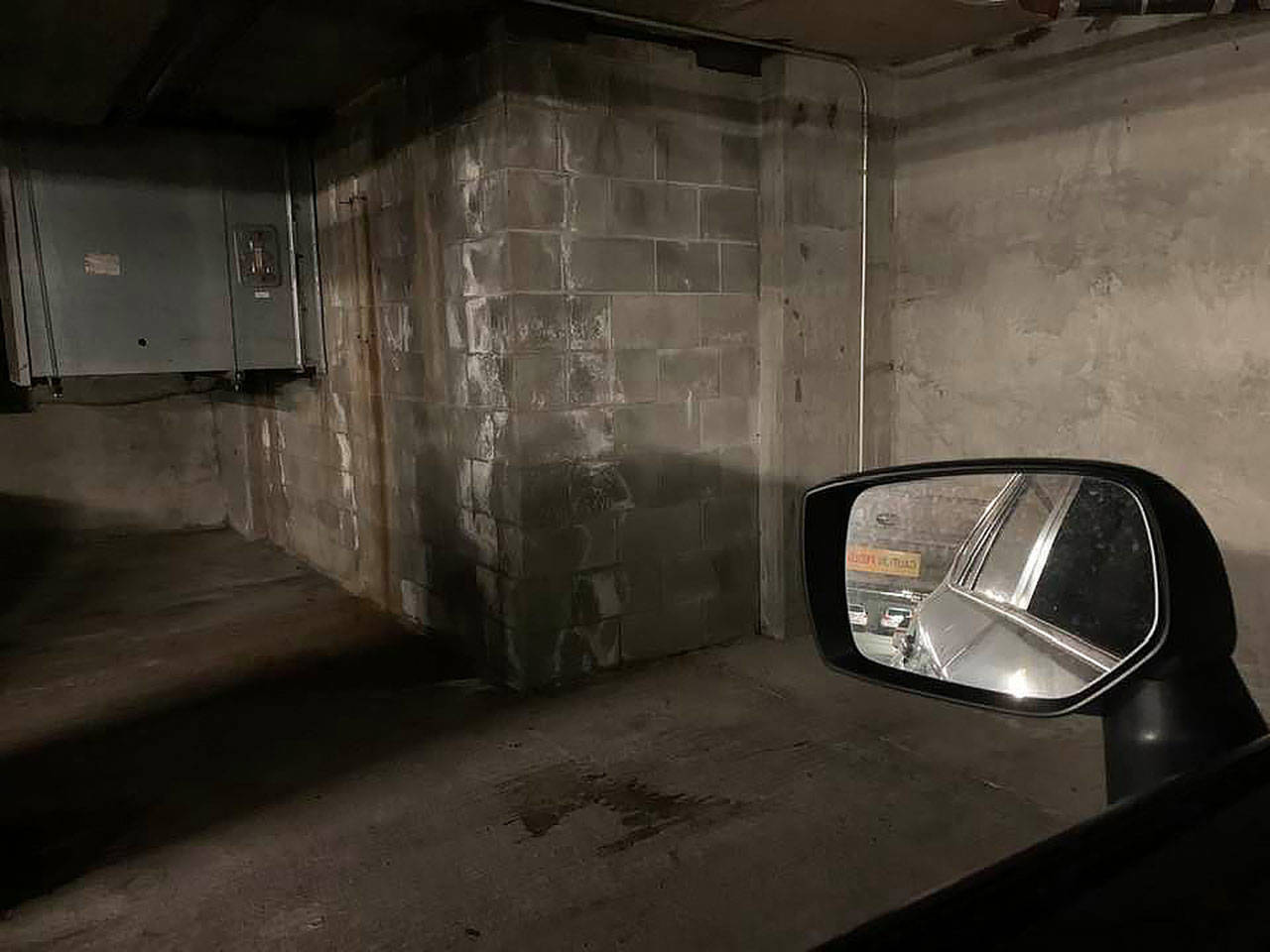

A nurse told Gorman to stay parked in a covered garage.

“This is not the American health system I imagined,” she said. “This is something out of a movie.”

As she waited in the driver’s seat, a nurse approached her car, then suited up in protective gear. Gorman cracked her door and leaned out for the nurse to swab her nose. The prodding reached all the way to her throat, she said.

By collecting the sample in the car, Gorman said, medical staff saved about three hours disinfecting a room in the office.

“I am so grateful my (rheumatologist) was flexible enough to do this,” she said. “But the fact I was tested in my car means we really don’t have a system for this, and that’s bad news.”

Now Gorman questions the wisdom of keeping schools in session.

It’s not just about the students, she said, but the staff teaching them.

“This whole disease will come down to decisions between dollar signs and lives,” she said.

In spite of government efforts to make more COVID-19 tests available to the public, the process has left many with symptoms frustrated and unsure who’s in charge.

President Donald Trump’s claim Friday that “anybody that needs a test, can have a test” hasn’t proven to be the case for many Snohomish County residents.

Mukilteo mother Heidi Marsh has been trying to get her sick son tested since early February. He was finally tested Wednesday, Marsh said. The process was grueling and riddled with conflicting information.

“I don’t even know how many fights I had to pick,” Marsh said. “I’m a bit of a momma bear.”

Her son, who has a history of a condition affecting his immune system, developed a deep cough and fever in early February, about a week before his 9th birthday. Marsh herself is on immunosuppressive medication.

“We are always very aware of how dangerous it could get for our family to be very sick,” she said.

After days with no improvement, Marsh took her son to urgent care. She’d seen headlines dominated by coronavirus.

Marsh asked about getting her son tested for the new virus, but was assured by doctors he probably didn’t have it, she said. He tested negative for influenza and strep throat, and they were sent home.

The boy’s condition had worsened by his birthday. He didn’t feel like going out for ice cream to celebrate.

“Something had changed in him,” Marsh said. “His cheeks were really flushed and he had spiked a 103-degree temperature.”

So she took him to the Seattle Children’s North Clinic in Everett, where Marsh was told her son had “an unknown viral infection in his lungs,” she said.

“That’s not comforting,” Marsh said.

Again, she pressed the clinic staff to test her son for COVID-19. Doctors told her he didn’t meet the requirements: recent travel to China or contact with a known coronavirus patient.

The boy grew more sick. By a fourth trip to the doctor, he was put on steroids and diagnosed with pneumonia.

On Monday, Marsh saw on the news that the restrictions for getting tested had been loosened, leaving the decision up to individual physicians. So she called her son’s doctor again.

“Nobody had their stories straight,” she said.

She was bounced from the doctor to the health district to the hotline and back again. Each person she spoke with gave her a different reason why her son couldn’t be tested. By Wednesday, Marsh said she gave up hope.

But that night, she got a message from her son’s doctor. It said to take her son early the next morning to a Northgate clinic, where he could get tested. So Marsh put her kid in the car, hoping she’d get some answers.

There, a doctor told her again the boy didn’t meet testing requirements. Marsh said she broke down in tears. Without a diagnosis, she didn’t know what to do.

“It will affect whether or not I stop taking my immune-suppressing meds, whether my husband goes to work or my child goes to school,” she said.

Later that day, Marsh got one more message from her son’s doctor. It said her child could get tested at the Everett walk-in clinic. When they arrived, Marsh was told the clinic wasn’t testing. She pulled up the doctor’s message — and that did the trick. Her son was tested. As of Friday, they were still awaiting results.

“You’re always told that the U.S. has the best health care system in the world,” she said. “You want to think that because we live here when (it) hits the fan, that we’re going to be in a much better position to handle something like this. … I am stripped of any belief of that whatsoever now.”

Marsh’s frustrations about getting a coronavirus test are not unique. Throughout the week, email inboxes and social media accounts at The Daily Herald have flooded with stories from frustrated test-seekers.

Husband was turned away from his primary doctor, 3 urgent cares, and finally the @OverlakeHMC ER because there are ZERO testing kits.

Soooo……………what now?

#seattlecoronavirus— Ange Garrett (@angemarie) March 4, 2020

Prior to the University of Washington offering tests this week, state labs just didn’t have the capacity to test anyone but the most dire cases, officials said.

The virology lab run by UW Medicine started working on a test when the virus with origins in China crossed the Pacific Ocean in January. But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention didn’t authorize them to begin testing the public until Feb. 29.

“In hindsight, there are things that could have happened to get this a little bit quicker,” said Keith Jerome, the head of the UW Virology Division.

Moving forward, Jerome said testing is the main weapon against COVID-19.

So why aren’t more people being tested?

“The public health system in our country is not always at liberty to do everything they want because they don’t have unlimited funds,” said Lisa Frenkel, co-director of the Center for Global Infectious Disease Research at Seattle Children’s.

She believes testing alone won’t be enough to get COVID-19 under control. Many young people who get the virus show few to no symptoms, so they unknowingly spread the disease to those more vulnerable, she said.

“I think anything that is transmitted asymptomatically is very difficult to contain by testing,” Frenkel said.

The demand for tests has also put a strain on local health care providers. They’re reporting high patient loads, limited capacity to evaluate patients in the absence of airborne isolation rooms, and diminishing stocks of protective equipment to guard themselves from COVID-19.

Tove Skaftun, chief nursing officer at Community Health Center of Snohomish County, a nonprofit serving mostly low-income patients, has continually posted on Facebook to deter unnecessary testing.

“There is no vaccine yet, nor medication to cure it,” she wrote. “This means that testing out of fear is not necessary or recommended. In fact coming to the clinic under these circumstances increases your chance of exposure. Testing should be reserved for for those who are ill enough to need medical treatment as it provides a diagnosis so we know what to do.”

But for those with symptoms, it seems the test offers a promise of clarity in uncertain times.

Sarah Brouwer’s son ran a fever on Sunday, with coughing and wheezing. The boy, 12, has asthma. He was vaccinated for the flu earlier this year.

So on Monday, Brouwer called their Woodinville pediatrics office to request a test for COVID-19. Since the boy hadn’t traveled to China, they were turned away.

By Wednesday, testing requirements had relaxed, so she phoned the office again and was told to call the Snohomish Health District. The district sent her to the hotline. She waited on hold until her call dropped. She tried again, the call dropped, and she gave up.

“It really made me realize the number of (confirmed COVID-19 cases) are really inaccurate,” Bower said. “If no one is confirmed they have it, how do we know what to do?”

Now, Brouwer said she’s worried about other kids who played an indoor soccer game with her son Sunday.

“I wanted him tested so I could alert the arena,” she said.

During a visit this week to the Snohomish Health District in Everett, Gov. Jay Inslee said the number of available COVID-19 tests is well above 1,000 per day. If approved, private centers could have capacity for tens of thousands of tests daily.

Inslee said the state would cover costs for those who are uninsured.

Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler issued an emergency order Thursday to health insurers to waive co-pays and deductibles for any patient who needs to be tested for the coronavirus.

Health officials recommend staying home if you’re sick, generally avoiding large groups and washing your hands. Scientists believe those with the disease are most contagious while actively showing symptoms.

As of Friday, it was up to individual providers to decide if a patient meets CDC criteria for getting tested.

Marsh, the mother of the 9-year-old birthday boy in Mukilteo, started to show respiratory symptoms herself this week. Doctors told her she did not meet the requirements for testing.

Julia-Grace Sanders: 425-339-3439; jgsanders@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.