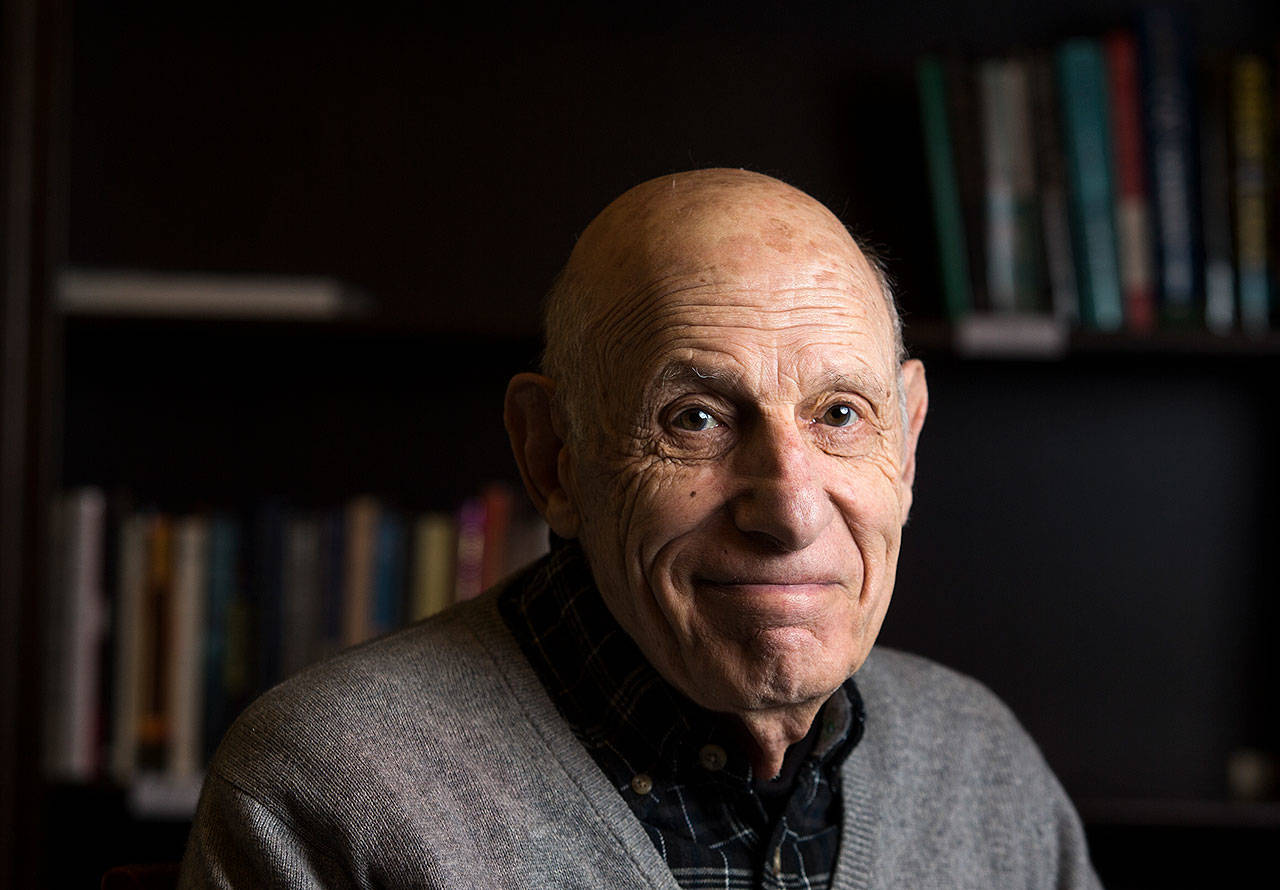

Editor’s note: This article about David Zinman, 90, of Mill Creek, and his story, “A 10-Cent Plaque” about his mom, was published in The Herald on Mother’s Day 2019. Readers enjoyed it so much we wanted to share it with you again.

MILL CREEK — Mother’s Day means big bucks for retailers.

People spend about $200 on Mom for gifts, cards, flowers, outings and pampering, which will amount to about $25 billion this year, according to the National Retail Federation.

Here’s a secret: You don’t have to drop a lot of money for your mom.

It’s the little things that make a lasting impression.

David Zinman, 90, can attest to that.

When he was 10, he spent a dime on a present for his mom, Florence.

It was a small wooden plaque from a Woolworth’s, with a simple four-line verse.

“I just wanted to give her something,” Zinman said last week in an interview at his Mill Creek home. “It wasn’t much of a present.”

He forgot all about it. But she didn’t.

Decades later, he found it in a drawer with her treasured items.

“When I came to collect her things after she died, she had it in with all her precious jewelries,” he said.

Zinman, a former Associated Press writer and Long Island Newsday medical and science reporter, turned it into a story called “A Ten-Cent Plaque.”

He offered to share it with readers of The Daily Herald.

“Why does that ten-cent plaque stay in memory all these years? You have to know something about the kind of person my mother was to understand,” he writes.

The story recounts the moxie of his tiny but mighty mom. Florence was born to Hungarian immigrants and grew up on New York City’s poor Lower East Side. She was a no-nonsense public school teacher.

“It seemed like she always taught school in tough neighborhoods,” he writes. “She used to tell me about her pupils like ‘Lefty Louie’ who wound up in the electric chair at Sing Sing Prison. But she never stopped trying to turn her kids around.”

(Though maybe it didn’t work for Lefty.)

And she didn’t let anyone push her around.

“Even in her 70s, when hoodlums knocked her to the sidewalk and snatched her purse, she showed a lot of spunk. She bounced up and took after them. If she had been a little younger, she would have caught them. The Daily News would have had a headline: ‘Mom Mauls Muggers.’”

Instead, she made front-page news a year later in June 1969 for an entirely different feat.

“My mom was sitting with some of her cronies, gossiping on a bench,” he said.

Up walked a hot young actress with a photographer.

“She asked if she could sit next to these ladies, and have some pictures taken,” he said.

His mom said, “Sure, darling.”

The darling was actress Faye Dunaway.

About a month later, his mom and her gal-pals wound up on the cover of New York Magazine. The headline referred to them as Dunaway’s “friends.”

His mom is shown sitting at the end, legs crossed, eyes shut, like she’s taking a snooze. People recognized her and stopped her on the street.

“She was a hero for a week in New York City,” Zinman said.

Maybe so, but the magazine wasn’t among the treasures in her drawer with the 10-cent plaque when she died in 1972 at age 81.

Zinman wrote “A Ten-Cent Plaque” when he worked at Newsday. He also wrote books: “50 Classic Motion Pictures,” “Saturday Afternoon at the Bijou,” and “The Day Huey Long Was Shot.” His plays were performed in Chautauqua, a cultural center in upstate New York where he lived after retiring. His wife, the mother of their three children, died in 2006.

Last year, he moved across the country to Washington with his partner, Kay, to be near her family. They live at Mill Creek Retirement Community.

Zinman doesn’t have the plaque, just the memory that he made his mom happy.

His inexpensive Mother’s Day present to her became a priceless gift for him.

Andrea Brown: abrown@heraldnet.com; 425-339-3443. Twitter @reporterbrown.

—————————

“A Ten-Cent Plaque”

By David Zinman

I will never know what made me reach into my mother’s old mahogany night table where she kept her treasured possessions next to her bed.

But when my fingers touched a smooth wooden object, I knew what I was holding even before I took it out. It was a 4-by-6 inch plaque I bought for her on Mother’s Day when I was 10 years old.

At that tender age, I had no confidence I could write anything meaningful. But I wanted to give her something to show her I remembered her special day. So I went to the five-and-ten cent store, and there I spotted a tiny Mother’s Day plaque with a four-line verse. It cost a dime.

Why does that ten-cent plaque stay in memory all these years? You have to know something about the kind of person my mother was to understand.

Her name was Florence — a name you don’t hear much any more. She was just over five feet tall. But she was a feisty lady who made most 20th century mothers seem dull by comparison.

She was a teacher in a public school in Harlem. To survive in that tough environment, she learned to be a disciplinarian. When provoked, she showed that same tough outer shell at home, too.

And I knew how to provoke her. I was an unruly hyperactive kid. I often disobeyed, talked back, and came home late for dinner with dirt on my face and holes in my knickers.

I was an only child and she was 40 when I was born. So I never knew my mother as a young woman. Only from pictures did I see her in her prime. She had wavy dark hair, sparkling brown eyes and flashing white teeth.

She was the third oldest of six children born to Hungarian immigrants who lived on New York’s poor lower east side. After high school, my mother went to teachers’ training school, then started a 48-year career as an elementary school teacher.

In 1925 when she was a young woman, she sailed to Europe. Aboard ship, she met my dad, also a teacher. It was a case of love at first sight. She told her mother, her traveling companion, that she had found her husband. They were married soon afterward.

He was her opposite in temperament, quiet and reserved. He was also intelligent and inquisitive, a Renaissance man. He played violin in an amateur orchestra, sketched in the Art Students League, and wrote poetry.

They were made a wonderful couple, sharing interests in music, the theatre, and golf. In a husband-and-wife tournament in Switzerland, they won an eight-day clock and a pewter trophy for shooting the lowest combined score.

I was born in 1930. She didn’t stay home long. She went right back to work after her maternity leave.

It seemed like she always taught school in tough neighborhoods. She used to tell me about her pupils like “Lefty Louie” who wound up in the electric chair at Sing Sing Prison.

But she never stopped trying to turn her kids around. After school, she went to their homes, the only white woman walking through black neighborhoods. “Hi, Teach,” kids yelled. She went to see their mothers, trying to get to the root of their problems. Sometimes, when she came home, she went to her room and closed the door. I could hear her crying softly.

Perhaps, she thought I would fulfill all those unfulfilled promises she saw in her young pupils. I can still see her applauding in the auditorium when I graduated from high school and then college.

When I got married, I remember her tiny figure looking after our car, shrinking in the distance as my wife Sara and I drove off on our honeymoon.

My father died a few years later. He had a heart attack and collapsed in the middle of the night. “Meyer,” she said as she clung to his lifeless body, “don’t worry. I’m not going to leave you.” When dawn broke, she still held him in her arms.

As the years passed, she retired and lived alone on a pension. But she never gave in to illness or, if she did, she never let me find out about it.

Even in her 70s, when hoodlums knocked her to the sidewalk and snatched her purse, she showed a lot of spunk. She bounced up and took after them. If she had been a little younger, she would have caught them. The Daily News would have had a headline: “Mom Mauls Muggers.”

The theft slowed her down but not by much. She still walked a mile every day. Then, she would join her cronies and read the newspapers on a park bench on Broadway.

One day, a beautiful young woman sat down next to her and asked if a photographer could take their picture together.

“Sure, darling,” Mother said.

A month later, she was on the cover of New York Magazine sitting next to Faye Dunaway. The headline read: “Is There a Life Beyond Central Park West? Faye Dunaway and Her Friends Think So. Learn About the West Side Renaissance.”

My mother loved her three grandchildren and she looked forward to playing with them at our home on Long Island. In her 80s, she was still shooting hoops on our makeshift basketball court in the driveway.

One winter day, I took a walk with her. She had to stop. She told me she had angina. We stood in a doorway out of the cold wind.

“How fast life goes,” she said as the pain subsided. “It’s like a dream.”

Then, one morning, she telephoned and asked me to meet her in her doctor’s office. I knew she must be very sick to do that.

The doctor took an electrocardiogram and told me to rush her to the emergency room. At Mount Sinai Hospital, they put an oxygen mask on her and admitted her. I stayed with her all day, and she seemed to be getting some strength.

At five o’clock, I asked if she would mind if I got a quick bite in the cafeteria. She told me she’d be okay. I left. That proved to be a mistake.

When I got back, there was a curtain around her bed. She had suffered a massive heart attack. An emergency team had not been able to revive her. She died alone among strangers.

That took place on May 10, 1972. She was 81.

All these moments rushed through my mind as I held the five-and-ten cent store plaque she had saved. It showed cuttings of lilies of the valley and white carnations next to a framed oval portrait of a woman. She looked like a prim and proper lady who would not have known the difference between a left hook and a right cross.

I brushed a thin layer of dust from the plaque. Its verse, written by a unknown poet, appeared under the title, “Mother.”

As I read it, I found I was saying the words out loud:

“Nearer and dearer than all on earth

Ever your face shall be.

Distance nor time can efface that day.

God linked your soul with me.”

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.