EVERETT — Yuki Tolmie was at a crossroads in her treatment this weekend when her husband of 47 years was cut off from speaking with her.

She’d been in the intensive care unit at Providence Regional Medical Center Everett since late February, when a neuromuscular disease seized her body and jeopardized her life. After weeks in the hospital, she had a choice to make: a throat surgery and long-term care, or remove the breathing devices and death, her husband Doug Tolmie said.

“We weren’t there for Yuki, and when she started to fail, we couldn’t help her,” he said. “No one could.”

Under guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to slow the spread of the new coronavirus disease COVID-19, hospitals and other health care facilities in Washington are restricting visitors. The worry is that any person who comes in may be infected, or bring in something contaminated by the virus.

Officials decided the risk to people who were already ill, as well as hospital staff, outweighed the benefit of visitation.

At Providence, those changes are in place indefinitely.

“Safety is our priority,” said Casey Calamusa, a spokesperson for Providence Regional Medical Center Everett, in an email. “To prevent the risk of spreading COVID-19 or exposing patients, their visitors and our caregivers, we have modified our visitation policy, in accordance with recommendations from the CDC.”

But it meant the Tolmie family couldn’t speak with Yuki, 72, who doesn’t own a cellphone or tablet. They also couldn’t talk to her on the hospital phone because she had breathing tubes in her throat.

“They have to proceed with caution, we get that,” Michi Tolmie, their daughter, said. “The separation just adds to the anxiety of everything else that’s going on, the uncertainty of the normal things we’re used to.”

Admission

It started with a fall.

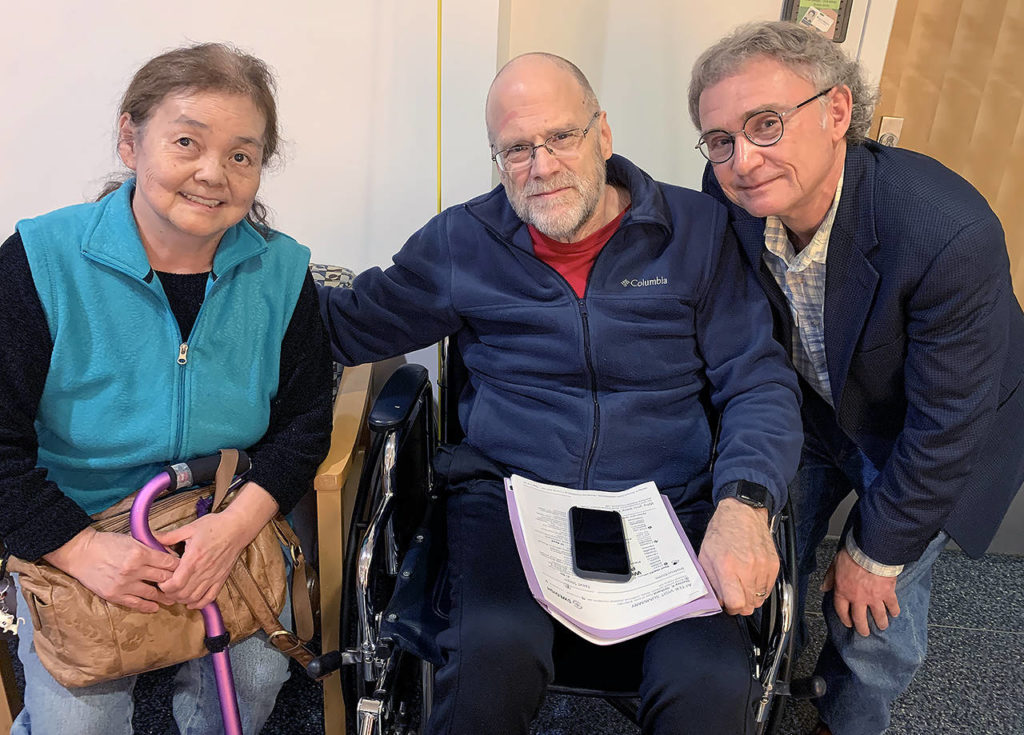

In late February, she wasn’t feeling well. Doug Tolmie, 68, thought it was a cold, or complications from her hip replacement last year. Then she collapsed Feb. 22 at their home near Lake Stevens and an ambulance took her to the Everett hospital.

A month earlier, the hospital at 13th Street and Colby Avenue had treated the first patient confirmed to have COVID-19 in the United States. The disease has killed thousands around the world and made thousands more sick, including more than 1,000 in Washington.

After eight days of tests, coronavirus was ruled out for Yuki Tolmie. Instead, the diagnosis was myasthenia gravis, a rare incurable neuromuscular disease.

“Once we knew the diagnosis, we knew who the enemy was,” Doug Tolmie said.

The fight was just beginning. She has been in the hospital since she collapsed. Her health deteriorated and she couldn’t breathe on her own. Yuki Tolmie was connected to breathing tubes for days. She struggled to communicate except by pointing or writing; both pose a challenge because of her disease.

Doug Tolmie visited her the afternoon of March 13 and left around 3:30 p.m., he said. He planned to return Saturday to be with her when the breathing tube was removed.

That night, following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance, the hospital restricted visitor access.

The new coronavirus — with symptoms such as fever, cough, pain, pressure in the chest and shortness of breath — is worse for people with underlying health conditions. Vaccines are being tested but none are approved. Government officials and health care experts encouraged “social distancing,” telling people to stay at least 6 feet apart. Many businesses were ordered to close or limit public access.

Even after learning his wife’s condition wasn’t improving, Doug Tolmie wasn’t allowed back.

“Within the intensive care unit, that’s life-and-death stuff and they need family members there,” he said.

The last visit

At Providence in Everett, the exceptions for visitors are parents and guardians of minors, those with power of attorney and those who need to be present for end-of-life.

“We understand the importance of seeing loved ones while they are receiving care, and know the value visitors bring to our patients,” Calamusa said. “During this time, we encourage our patients and their loved ones to communicate more through phone and video calls.”

After taking to his Facebook page, speaking with the hospital chaplain and other officials, the hospital allowed Doug Tolmie to see Yuki on Monday. Based on earlier calls with doctors about her condition and previous conversations, in which his longtime wife told him she didn’t want to be in a nursing home, he wondered if it would be the last time.

“I knew at the very least I’d be able to go in and say goodbye to my wife,” Doug Tolmie said, through a cracking voice.

All visitors are screened per Providence rules. If they have a fever, cold or flu-like symptoms, they’re not allowed in.

“I’ll tell you, getting into that place, it’s a challenge,” Doug Tolmie said. “Providence is not the bad guy. Providence is the good guy. They’re doing everything they can to lock this down.”

She couldn’t really talk because she was hooked up to breathing devices again. On a piece of paper the husband wrote “tracheostomy/nursing home” on one half, “die peacefully” on the other. Then the doctor came in and asked Yuki about her choice. She pointed.

“She chose life,” Doug Tolmie said. “She decided this was worth a chance.”

He knows he’s lucky. Walking past other would-be visitors outside the hospital made him feel awful, he said. He wants to help them and others communicate if they can’t go into a hospital to see someone.

“It’s been difficult, but we’re not alone,” Michi Tolmie said. “There are a lot of other families out there in our situation, if not worse.”

Doug Tolmie advised other families in a similar situation to give a cell phone or tablet to their ill loved one, along with the necessary charger, when they’re admitted to the hospital.

Staff are often unable to answer the phone for patients, because they’re busy tending to others. Doug Tolmie wants to work with Providence to see if donated devices — cleaned and sanitized — can be used by patients or volunteers, for those who can’t dial and speak.

“We’ve now got an option that might work — might,” Tolmie said. “I’m still in the same position, I can’t talk to my wife. I cannot communicate with her.”

But his idea is unlikely to be put into action. Providence, with two major hospital campuses in north Everett, had a volunteer program with more than 600 people that it suspended, because they weren’t classified as essential personnel. Instead, those volunteers are treated like visitors and not allowed inside until further notice.

For now, at least Doug Tolmie knows his wife wants to live.

Ben Watanabe: bwatanabe@heraldnet.com; 425-339-3037; Twitter @benwatanabe.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.