EVERETT — Erik Stewart was just trying to get some sleep. On Monday night, he said, Everett police asked him three separate times to move when he was resting on the street.

Stewart sat on a bench in Clark Park next to his wheelchair Tuesday morning. He’s been homeless seven months, since he lost his housing while in the hospital for congestive heart failure.

It would be nice, he said, to have a place to sleep and “not feel like you’re doing something criminal” by lying down.

Lying down is against the law in newly expanded “no sit, no lie” zones around Everett.

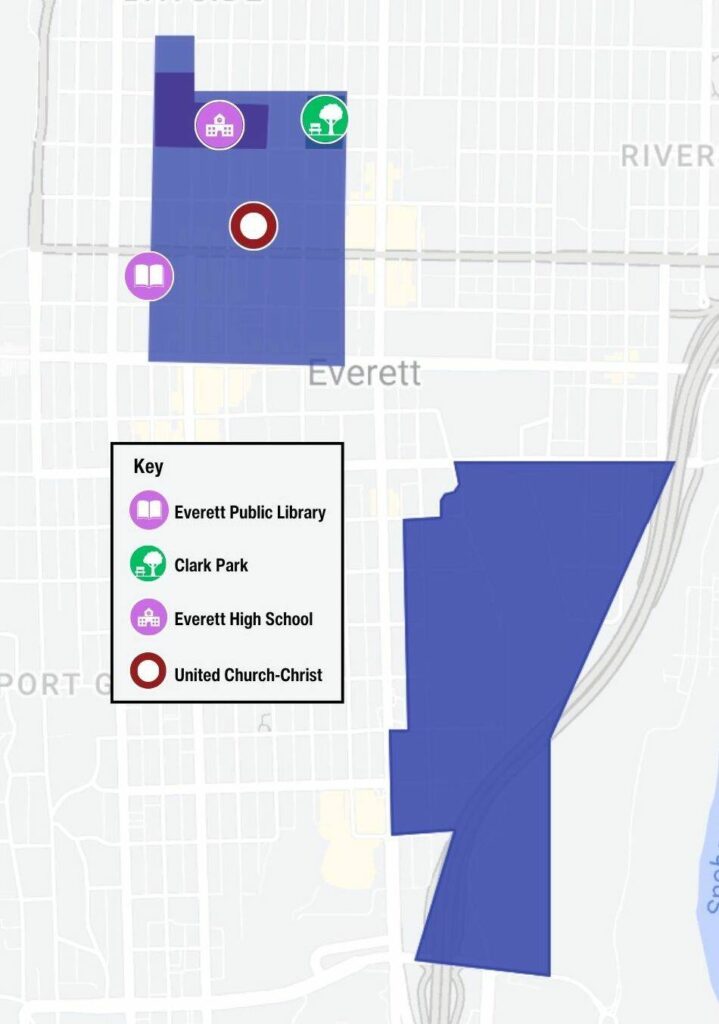

Stewart is one of several homeless people who said there has been an increased police presence on the streets in the past few weeks, coinciding with the creation of two new zones: roughly 68 acres of downtown Everett, plus about 300 acres around the Fred Meyer at 8530 Evergreen Way.

Police spokesperson Ora Hamel confirmed in an email: “We have maintained a highly visible police presence in the buffer zones as well as other areas that have been heavily impacted by criminal activity.”

“No sit” has been the subject of much debate since the City Council expanded a 2021 law in May to allow Mayor Cassie Franklin to establish new zones as buffers to service providers and areas “highly impacted by street-level issues.”

Recently, the mayor designated the first buffer zones since the new code was approved. Sitting or lying down in the zones is forbidden, as is giving out food, services or supplies without a permit.

City staff declined an interview through spokesperson Simone Tarver.

“Service facility buffer zones are meant to be a tool that provides additional options to help keep our community safe and ensure support is available for those who are struggling,” Tarver wrote in an email.

The debate over “no sit, no lie” has pitted homeless people against business owners trying to stay afloat. It’s a familiar story for those who remember the controversy over the 2021 law, which created a buffer zone around the Everett Gospel Mission.

David Farrell owns Ed’s Transmission Service at 1811 Everett Ave., near the center of one of the new zones. He believes police should have more power.

“Lawlessness in this city is ridiculous,” he said, pointing to litter, vandalism and drug activity.

He has called the police before about a drug deal happening outside his shop, he said, but they did not have probable cause to search people when they got there.

Still, the “no sit” law won’t help, he said, because people are “just gonna move.”

Farrell does not believe those issues have harmed his business, however.

The Chevron on Broadway at Everett Avenue is right outside the new zone. Homeless people often come into the convenience store, said William Mull, a clerk. They ask for water or expired food. Sometimes they just need a place to rearrange their belongings. Mull feels compassion for the people coming in.

Around where he grew up in Everett, Mull said, everybody is “two weeks from the street.”

Sarah, a Chevron coworker who declined to give her last name, said she goes through $500 of her own money every two weeks feeding people and providing other help.

She can tell a lot of them are new to being homeless.

Dealing with the influx of people is challenging. At times, they have to ask people to leave if they’re taking over a parking stall or hanging out in the car wash. That can be difficult, as many are dealing with serious mental health problems and sometimes don’t seem to understand.

Sarah has had her car vandalized for asking people to leave, she said.

More police in the area could help, Mull suggested, if they maintained a consistent presence on the street instead of driving around in cars.

He and Sarah both disagree with the “no sit” law.

If the city is going to make a law like that, Mull said, they need to have a place for people to go.

“Where to go?” is the pressing question.

On the outskirts of downtown Everett last week, a handful of people gathered on a patch of grass next to busy Broadway at Hewitt Avenue, on the other side of the street from where sitting is banned. Some personal items — a bike or two, a blanket covering the ground — lay around them.

They were wary of giving their full names to a Daily Herald reporter, but had something to say about “no sit, no lie.”

To Frank, who declined to give his last name, “it’s obvious that they’re trying to push us homeless people out of town.”

Jason, who also opted to give only a first name, echoed Frank’s feelings of being targeted.

The city is “just attacking the homeless,” Jason said. “Instead of helping us, they just want to put us in jail.”

Everywhere he goes, he said, city workers tell him he’s in a “no sit” zone.

Officer Hamel said in an email that police are focusing on educating people about the zones and social services, which “could pivot to an enforcement situation on a case-by-case basis.”

“The ordinance requires law enforcement issues a warning to individuals not adhering the rules of the buffer zones,” she added, “the Department will adhere to these practices.”

Keinen, who also declined to give his last name, came over to join Frank and Jason on the grass. He has been arrested a number of times in the past two years, he said, once for “walking down the sidewalk.”

Two years ago, he came to Everett from Arlington because he’d heard of Cocoon House, a nonprofit with a youth shelter and young adult housing programs. Mayor Franklin is its former CEO.

Keinen, 22, said he’s on a list for housing there.

He’s looking into other options too, he said. He doesn’t want to be homeless forever.

No one in the group was clear on exactly where the new zones were. The city does not intend to put up signs letting people know where the zones begin and end.

In a council committee meeting late last month, the city’s Government Affairs Director Jennifer Gregerson explained the reasoning by saying the city could put a sign up and “someone just crosses the street,” dodging information about social services.

That policy is problematic for Penelope Protheroe. She’s the founder and president of Angel Resource Connection, a nonprofit giving food and support to people on the street.

Homeless people have no easy way to find out where the zones are, she said. Though some have phones, they often have no internet on them. The code specifies zones can have up to a “two-block radius,” but Protheroe says that can be misleading.

People think they can just walk two blocks and be out of the zone, she said. In fact, the boundaries of the downtown Everett zone extend for five blocks total.

Of that zone, she said, “it’s right in the heart of where the homeless go to get services.”

Homeless people are spreading out because of the law, she said, losing touch with each other as well as service providers.

“Talk about being lonely,” Protheroe said. “Talk about being isolated.”

Nick Breda, who said he’d been sleeping on the streets for around two years, also said people have been scattering. They’re scared they’ll be arrested, he said.

Breda was at Clark Park on Tuesday morning with Stewart.

“Holy mac and cheese,” he said, when shown maps of the two new buffer zones. “Wow.”

He understands the city is up against difficult problems, but he doesn’t believe the zones are the answer.

Putting people in jail doesn’t solve anything, he said.

Stewart also disagreed with the law.

He’s gotten some help from the state Department of Social and Health Services, he said, but feels too “broken” to look for housing.

Before he was homeless, Stewart said he ran his own concrete business for 25 years. He lost his retirement in 2008 when the stock market crashed.

“You can work all your life,” he said, and end up on the street.

Sophia Gates: 425-339-3035; sophia.gates@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @SophiaSGates.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.