EVERETT — Around the time a group of Iranian students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took dozens of Americans hostage, Mohammed Vahid Danesh-Bahreini and his roommates were just hoping their Ford Torino wouldn’t conk out — again — between their Marysville apartment and Everett Community College.

They, too, were Iranian students, but far removed from the Islamic revolution that toppled the Western-backed monarchy of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in February 1979 and led to the embassy takeover eight months later.

The dozen students in Everett just wanted to earn their credits and transfer to a four-year university.

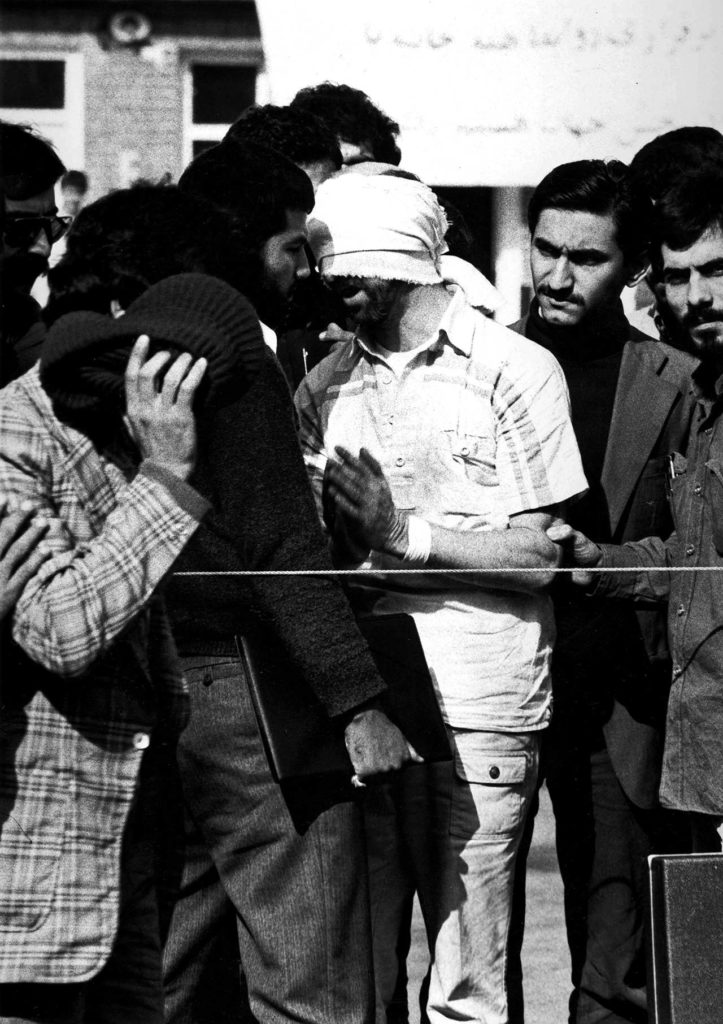

Monday marks 40 years since the Nov. 4, 1979, raid of the embassy. A week later, the United States froze Iranian assets, and, for many of those students in Everett, their tuition money dried up. All the while, Iran was moving closer to war with Iraq, an eight-year conflict that began in 1980 and claimed the lives of 500,000 soldiers.

Danesh-Bahreini worried about his family, friends, homeland and future. He was nearing midterms and it was a matter of time before the college would hit him up for tuition.

He was called into Bill Deller’s office, his heart beating fast as he feared he would be sent home. The first time they’d met, the dean of students treated him kindly. At the time, Danesh-Bahreini was a prospective — albeit desperate — student trying to find a college that would let him enroll despite his marginal English. Deller saw potential where other colleges had not.

On this occasion, Deller asked about the tuition money and if he had a job. Danesh-Bahreini explained that he couldn’t pay and didn’t want to work under the table because it could jeopardize his student visa. Deller said they’d go to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service office in Seattle the following Monday for a work permit.

Danesh-Bahreini had his doubts: “I’m thinking, ‘Who the hell does he think he is? Superman? Immigration? How is he going to do this?’”

That Monday, in downtown Seattle, Deller left Danesh-Bahreini to go into a lengthy meeting behind closed doors.

Deller described it as a chat, but Danesh-Bahreini remembers the dean coming out “all red and sweaty,” as though he’d made a long and forceful argument.

“Come on in,” the immigration official told Danesh-Bahreini. “Bring your passport.”

That day Danesh-Bahreini got his work permit.

Deller told him to show up to the college library the next day to work in periodicals.

Other Iranian students also received work permits. An account was established to help them with living expenses. Tuition, too, was covered, and Deller often would stop by their homes with food that had been donated by faculty and students.

As American flags burned in Tehran in the fall of 1979, Danesh-Bahreini and his classmates found a home on a faraway community college campus that embraced them. Forty years later, they’re still grateful.

Sharing the story

Kaveh Danesh is Danesh-Bahreini’s son, and he is brilliant.

He graduated from Duke University with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and minors in English, philosophy, Chinese, chemistry and neuroscience. He spent a year in China as a Fulbright Scholar. He earned a master’s degree in statistics from Harvard and interned at the White House. He’s now working toward a doctorate in economics at the University of California at Berkeley and a medical degree at the University of California, San Francisco.

His research into ovarian cancer screening has been published in the Journal of Theoretical Biology. He received a mathematics fellowship from the Department of Defense. He recently finished second in a national poetry contest among hundreds of medical students.

Danesh, 29, grew up in Bellevue listening to his father’s tales about how Deller and others at the college in Everett helped him in his time of need. After college, when he was trying to figure out what he wanted to do with his life, those stories began to sink in.

“It helped me realize how one person’s kindness could affect multiple generations,” Danesh said.

In July 2017, Danesh bought two Everett Community College T-shirts and gave one to his dad. An image of the father and son with their shirts was posted on Instagram, which came to the attention of Katherine Schiffner at EvCC.

The director of public relations contacted the family to say the college would share the news with Bill Deller, who was then 95.

“They were astonished to learn that Bill was still alive,” Schiffner said.

Since then, the trio has met several times. Sometimes Danesh’s sister, Bahareh, joins them.

The children see kindred spirits when their dad gets together with Deller. Both, they say, have worked hard to help others. Bahareh has accompanied her dad when he has delivered food and supplies to the homeless on Everett’s streets.

Danesh doesn’t know what he will do when he finishes up his doctorate and medical degree.

“I’d like to be a professor,” he said. “And maybe someday a dean, to hopefully be to others what Bill was to my dad.”

Culture of compassion

Bill Deller was finishing his bacon and scrambled eggs at Sister’s Restaurant in downtown Everett when a man stopped by to greet him.

Deller was Jerry Solie’s Everett Community College track coach in 1956, and they can still share a laugh over a 63-year-old memory.

“(He) remembers I dropped the baton,” Solie said.

“I’m not the only one,” Deller said without missing a beat. “The whole track team does. Stay out of trouble, Jerry.”

Deller is 97. His mind is sharp. He has aviation books on a table by his easy chair at home along with the latest edition of The Economist. Nearby is an album dedicated to his wife’s memory. He keeps a 1940s black-and-white photo of her in his wallet.

Lois Deller died in 2009. He courted her while stationed in Guam during World War II and later proposed to her by telegram when he was living in Oregon and she in Massachusetts. Her engagement ring arrived by mail.

Deller has served in many roles in a life that began in 1922 in a tiny South Dakota town.

He was on the University of Oregon track team. He enlisted in the Navy during World War II. He flew the Navy version of the B-24 over Japanese-held islands for pre-invasion photographs. For a short time after the war, he was an Alaska Airlines navigator out of Paine Field. He retired from the Navy Reserves in 1969. He also was an extra in the 1948 western “Rachel and the Stranger,” starring Loretta Young, William Holden and Robert Mitchum.

He taught and coached at Everett High School and when he wasn’t making enough money to support his growing family, he tried his hand at selling insurance and Fuller brushes. He went SCUBA-diving for logs and worked on the green chain at an Everett mill.

Legendary Everett High School coach Jim Ennis spotted him on the street one day and told him to go to the college and a job would be waiting for him. It was at the college that Deller made his most memorable mark. Today, an outdoor plaza on the campus bears the Deller name.

Deller started in 1955 as a coach and PE instructor. He also taught aviation maintenance and coached several sports. In 1968, he became the dean of students.

Amid the backdrop of the civil rights movement and the turmoil of the Vietnam War, the late 1960s were challenging for deans of students across the country. Deller dove in. As soldiers returned, some struggling or unable to walk, Deller crisscrossed the campus in a wheelchair to find trouble spots, and enlisted maintenance staff and carpentry classes to make the fixes. He became the first advisor to the Black Student Union and eased friction among immigrant students from Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.

Mike Deller attended EvCC while his dad was the dean of students. “I think he created a culture of compassion,” said the 1971 graduate who went on to become a bank manager and Port of Everett CEO. “I think it was that culture that became pervasive, and I think to this day there is a culture of compassion and inclusion.”

During the hostage crisis, Bill Deller spoke up on behalf of EvCC’s Iranian students. “These are 12 neat people caught in the middle of a bad situation,” he told the student newspaper, The Clipper. He called anti-Iranian graffiti that cropped up on campus “a display of sickness.”

Off campus, some of the Iranian students would occasionally hear racially tinged whispers and Danesh-Bahreini has seven stitches above an eye to remind him of the day he was struck with a pool cue by someone who did not want him around.

The Iranian alumni know that many people from the college came to their aid. They rattle off the names of faculty — instructors David Utela in engineering, Nancy Howein chemistry and Richard Hyman in math — and know there were people behind the scenes in financial aid, counseling and the registrar’s office as well as fellow students who helped them.

Through their eyes, Deller became the face of the many.

“It’s selfish for me to say how he helped me because it wasn’t just about me and it wasn’t just about Bill,” Danesh-Bahreini said. “It was a community of everybody.”

The graduates

Many of the Iranian students have stayed in close contact over the years. Most stayed in America.

They have been remarkably successful.

Danesh-Bahreini worked for Boeing before striking out on his own. Today, he’s president and CEO of three companies that cover engineering and construction, real estate and mobile app development.

His brother, Farid Danesh, earned a degree in business and was in the car trade in California for 35 years.

Ali Amiri earned a civil engineering degree, has been working for the state Department of Transportation since 1984, and is now a design engineering manager for the Highway 99 tunnel in Seattle.

Homayoun Farange graduated in mechanical engineering, lives in Mukilteo, and has worked for Boeing since 1986. His three children graduated from the University of Washington.

Fariba Ghorbani was the lone woman among the 12 Iranian students at EvCC back then. She’s a counselor in private practice.

Mansoor Ghorbani is a civil engineer who worked for the state Department of Transportation and the cities of Chehalis and Olympia before going into real estate investing.

“It’s amazing how much these people contribute to their country,” Deller said. “They are American citizens now.”

Amiri, the WSDOT engineer, remembers Deller showing up at his Marysville apartment with homemade apple and pumpkin pies around Thanksgiving 1979, a few weeks after the 52 hostages were taken in Tehran. It was a reassuring gesture.

“His compassion and love for a bunch of foreign students was and still is paying dividends,” he said.

Paying back

The Everett Community College Foundation was established in 1984. The first foundation director was Bill Deller, by then EvCC’s former dean of students.

Mike Deller remembers those early days of fundraising. “He was walking down the street with a tin can, basically.”

In 2018-19, the foundation awarded 256 student scholarships, for a total of $415,925. It also contributed $443,369 in support of 45 college programs.

The current assets for the EvCC Foundation are $5.6 million.

Bill Deller still manages to pitch in $2,000 a year.

Danesh-Bahreini knows that. These days, the Iranian-born student who once feared he would be kicked out of school and the country because he couldn’t pay his tuition, matches Deller’s donation. He also ups the ante. His check last year was for $2,000.96.

Last week, he wrote another for a penny more.

“The cents reflect Bill’s age,” Danesh-Bahreini said. “And he knows that I told him every year it goes up by a cent and he should live forever.”

Eric Stevick: 425-339-3446; stevick@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.