EVERETT — Night after night when the kids were asleep, they’d open boxes holding the most horrible stories a person can imagine.

Thousands of hours were spent in their living room, trying to make sense of the terrible things that people have done to each other.

Often when attorney Lisa Paul prepared for a trial, she’d feel wound up, nervous and discombobulated. She would run her arguments by Mark Roe, the elected top prosecutor in Snohomish County since 2009.

“He’d condense it all down to to one sentence,” she said. “Everything fell into place. I knew what I was going to do and how I was going to do it.”

Sitting next to her in a courtroom, Roe explained, “I can synthesize things down to one sentence because that’s my attention span.”

At times that can feel like a jury’s attention span, too, he joked.

Over the past three decades, the pair has tackled some of the most heart-wrenching, high-stakes, hard-to-prove crimes in Snohomish County. Rape cases with no physical evidence. Child abuse. Murder.

Quietly, behind the scenes, they’ve been married 25 years. They raised two boys and a daughter. If one of them was knee-deep in a trial, the other became a single parent for as long as the case wore on.

Paul, 60, retired from the prosecutor’s office in 2017.

Roe, 59, retires this month, a move forced in part by high blood pressure and an aneurysm in his heart. He endorsed his successor, Adam Cornell, a deputy prosecutor who ran unopposed in November.

Reflecting on his decade as the county’s lead prosecutor, Roe wants the record to be clear that, while he had the title, it shouldn’t overshadow all of the work he and Paul did together. He never made a decision on a charge, trial or anything important, he said, without talking it over with his wife. He’d bounce ideas off of her, as she did with him.

Roe speaks freely. Paul is careful and deliberate. Sometimes, she said, she’d interrupt and tell him, “Well, I don’t think you want to say that.”

“I need to be reined in sometimes,” Roe said.

“Right,” Paul said.

Roe grew up in Seattle, the son of Ellen Roe, who served for decades as the “most blunt member” on the Seattle School Board, according to an obituary this year in The Seattle Times. Mark’s sister, Becky, co-founded the Special Assault Unit at the King County Prosecutor’s Office in 1979. Her work inspired her brother to go to law school, with his sights on becoming a prosecutor.

Paul attended Lewis & Clark College. She worked in a public defender’s office in Oregon decades ago, writing appellate briefs for defendants who couldn’t afford to hire a lawyer. One day she was looking over the case file of a serial killer who’d gone up and down I-5 murdering women late at night. Digging through the old reports, she discovered a good friend from high school was one of the victims.

“It made it really real for me,” Paul said. “Then I thought: ‘I think I just don’t want to do this anymore.’”

She tried working at a private firm in Seattle, in a tall building with a nice office and all the perks, she said. She didn’t like it.

She landed at the Snohomish County Prosecutor’s Office in 1987. Roe had been a prosecutor for a year. The two did not click.

“I took an instant dislike to her when she got here,” Roe recalled.

“It was mutual,” Paul said.

Over time those feelings thawed.

“It is not unusual at all,” Roe said, “in the legal system or any profession that you can name, that people who work together, particularly when they’re smart, vibrant, interesting people, who share the same interests — sometimes there is a spark.”

Others noticed their chemistry before they did.

“Being around her and watching her work, I couldn’t help but recognize that she was brilliant,” Roe said. “I admired her toughness and the way she did her job. And I just wanted to be around her. I didn’t think there was any way in hell she wanted to be around me.”

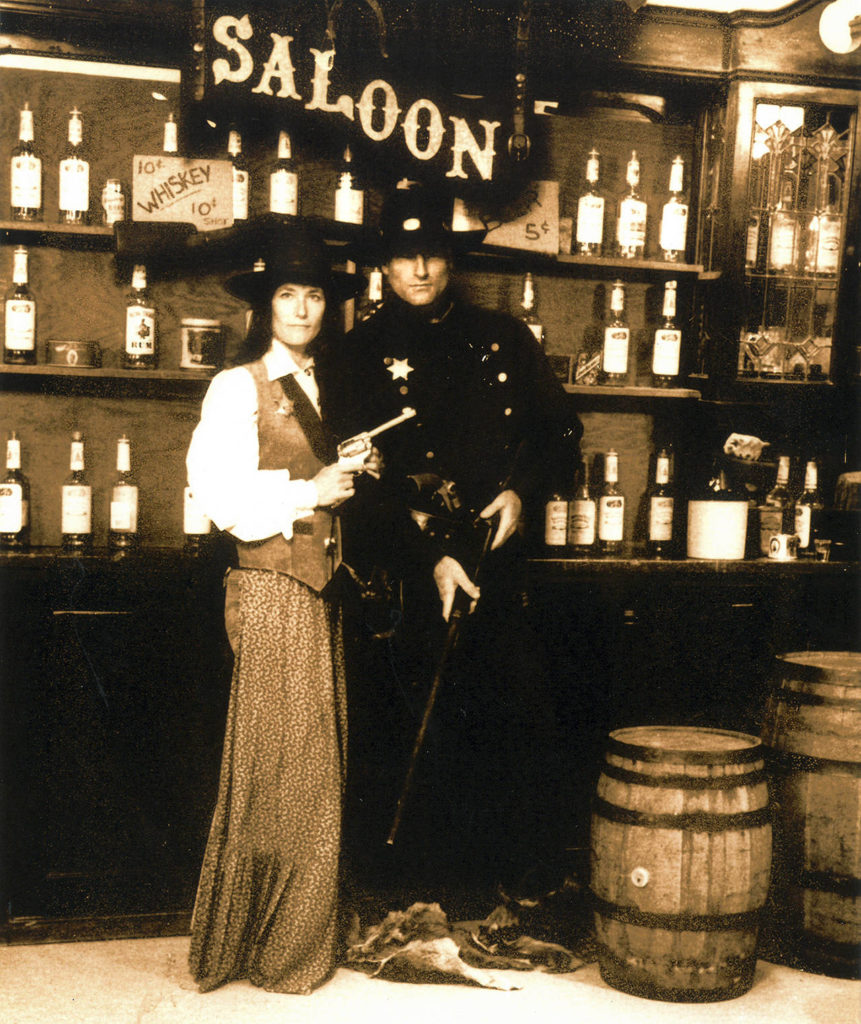

He was wrong. But both had other spouses at the time. They’re not eager to talk about those days. They divorced, then married each other, spur-of-the-moment, on a trip to California. On their honeymoon, they dressed as sheriffs from the Wild West for a sepia-toned snapshot. Paul didn’t take Roe’s last name. At work, they didn’t want colleagues to feel weird. Their marriage wasn’t a secret, but it wasn’t broadcast.

Some new hires gasped, Roe said, when the two kissed at Paul’s going-away party. They never sat together at the counsel table in court. But at recesses, they had an honest critic they could consult in the gallery.

“Sometimes things went bad, and there were times I would have real self-doubt about how I was doing or how things were going,” Roe said. “She would be there in my trials more than I would be there in hers, for the simple reason she didn’t want me there.”

“Sorry,” she said.

“And — why, specifically?” Roe asked, turning to Paul. “Why didn’t you want me there?”

“I wanted my focus here,” she said, waving to the jury box and bench, “and not thinking about my husband in the back.”

“So I would sneak in at times,” Roe said, “because I wanted to see her put into action whatever we would talk about.”

For years, Roe and Paul traded off as supervisor at the Special Assault Unit, the team investigating sex crimes. Of the sex abuse cases that reach the prosecutor’s office, about half have enough evidence to bring charges. Then there is the other half.

“Lisa and I had many of these over our careers,” Roe said. “… We know it happened, but we know this case isn’t going anywhere. We can’t prove it, and we decline it. It’s better than the alternative of charging that case, because of all the damage that will be done to all the people, toward no end whatsoever. But those are hard. Those keep you up at night.”

No one can witness trauma up close every day without it exacting a toll. For Paul, the rise of the internet meant she not only had to hear about the worst thing that ever happened to someone. She had to watch video.

“It got to me,” Paul said. “I felt like I had this level of sludge in my body, and it kind of weighed me down. It kept getting more and more piled on, every time I did it. You almost have a form of PTSD after a while.”

Counseling helped, she said.

“Sex offenders, they’re not going to stop until something stops them,” Roe said. “So it takes a certain type of person to handle those kind of cases, and to lead other people who are handling those kind of cases.”

Around 1,100 children a year receive services at Dawson Place in downtown Everett. Paul served on a task force that dreamed up the one-stop center for kids who have been abused. It opened in 2006, moving into a new space on California Street in 2010. Victims are seen by a nurse, interviewed by a trained professional and connected with one of 13 therapists, all in a safe, supportive environment.

Roe served on the board for Dawson Place, as president at times.

What happens there can determine if a kid will live the next 80 years damaged and hurting, or healthy and hopeful, Roe said.

Their work days never truly ended. On the longest days, Roe worried about Paul walking alone to her car at 12:30 a.m.

When they drove home together, they talked about cases.

In the house, they talked about cases.

Their kids grew up in a family with two prosecutors and no defense attorneys, Roe said.

“We honed our cross-examination skills on them,” Paul said.

“That’s what we like to call maximum accountability,” Roe said.

Roe speaks in the language of baseball. He doesn’t keep batting averages for cases won and lost, and he doesn’t know anyone who does, he said. Some cases feel like staring down a 95 mph fastball while a catcher’s needling you, the crowd’s screaming and the umpire doesn’t call a perfect strike zone — but you’ve got to stay focused on the ball. The first voice their first son heard in the delivery room was Seattle Mariners announcer Dave Niehaus, during a game against the California Angels on Aug. 2, 1995.

Roe coached basketball and Little League.

“He always, always, always was there for our kids,” Paul said. “He spent time with them. He played with them out in the yard. That, more than anything, is the thing I’m proudest of him for.”

At every chance, he’d catch Mariners games with the kids.

“It’s interesting that — y’know — you think I was so attentive to the kids and was a good dad,” Roe said to Paul, “because I always felt that because of the job, that they didn’t get all of us that they should’ve. It was completely all-consuming at times.”

Once during a murder trial that Paul prosecuted in the 2000s, the family had to flee their home because of death threats. Detectives found their property had been mapped out, with grave sites marked, and a plan to burn down the house. It looked credible. Cops in riot gear patrolled the lawn. A neighbor came over to return mis-delivered mail and got the surprise of his life. The family spent Thanksgiving at a hotel in Bellevue.

But in the courtroom, Paul didn’t let on that anything was awry. She was unflappable, Roe said.

When Roe retires, he and Paul plan to move out of the county. Here, every place they go is a reminder of a body that was found, or a child who was hurt. Paul struggled to explain exactly why she kept coming back to work on those cases, the hard ones.

“I felt pretty early on that kids are great, they’re pretty resilient, even when they’ve had terrible things happen to them, and they’re fun to be around,” she said. “Who wouldn’t feel good about that? You’re really helping people, really vulnerable people. I don’t know the right words. Mark, give me some words, please. Give me my sentence.”

“You knew you were good at it,” Roe said.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.