TULALIP — Study after study has shown Native American mascots can be harmful to youth.

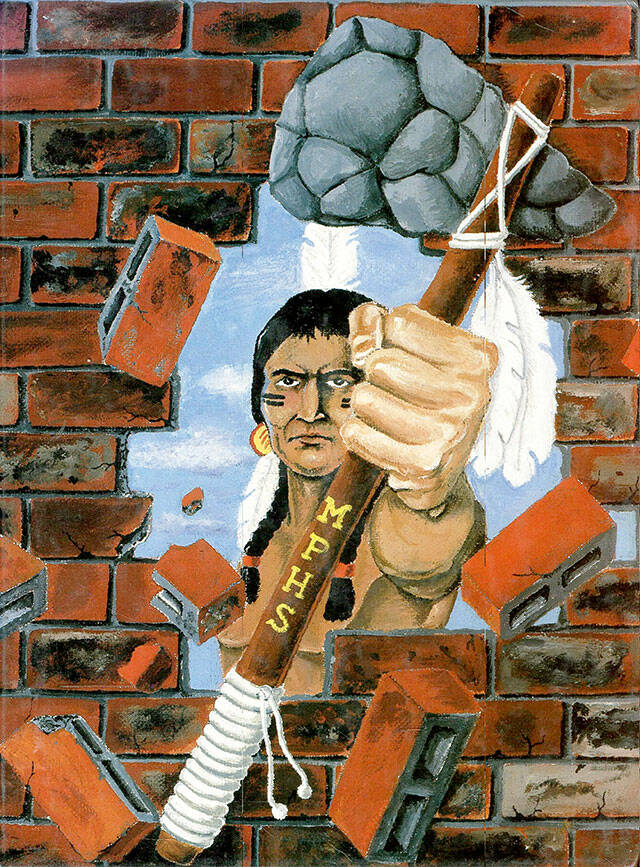

Yet the Marysville School Board voted last week to retain the Tomahawks mascot at Marysville Pilchuck High School — though it may soon look different. And they could still change their mind, School Board President Paul Galovin noted.

Stephanie Fryberg, a University of Michigan psychology professor who has studied the negative effects of mascots, questioned the school board’s decision in an interview with The Daily Herald. She’s a Tulalip tribal citizen and a 1989 graduate of Marysville Pilchuck High School.

“How many kids do we think it’s OK to bully? Five, 10?” Fryberg said. “But there have been many more than five, 10 Native youth who have called for this to be gone. In fact, the tribes’ youth council voted for it to go.”

State House Bill 1356 banned the use of Native American names, symbols and images as mascots, logos or team names. All public school districts in the state of Washington were required to consult with neighboring tribes to pave a path forward. Tribes could veto the use of mascots they deemed inappropriate.

The Tulalip Tribes asked the district to remove the mascot after hearing from the youth council last year. Some of the youth cried while sharing their experiences in Marysville schools, Tulalip Tribal Chair Teri Gobin said.

In the fall, the Tulalip Tribes’ semiannual general council voted in favor of maintaining the Tomahawks mascot, by a vote of 92-83. The school board cited that vote in their resolution.

Ultimately, the tribes left the mascot decision in the hands of the school district. The school board chose to keep the mascot, while redesigning the logo to “ensure that it does not discriminate or disrespect the Tulalip Tribes or any Indigenous community.”

It’s more of a placeholder, Galovin said. The district could still change the mascot, but they want to continue the conversations with tribal leaders, advocates and students, Galovin said. The end goal, he said, is to halt the discrimination Tulalip students say they experience in Marysville schools.

“More than two decades of research demonstrates that Native mascots decrease Native youths’ self esteem, feelings about their community, their communities work, and their academic aspirations,” Fryberg said. “These mascots increase stress, depression, and suicide ideation among Native people, and they undermine cultural connection. And so to hold on to these mascots, in an academic setting, where we’re supposed to be giving children opportunities for the future. It makes no sense. It’s really painful.”

When she was a student in the Marysville district, Fryberg said she had a number of experiences where teachers had low expectations for her, solely “because I was Native.”

When one middle school teacher found money missing from her wallet, Fryberg recalled, the teacher pulled her and other Native American students aside and asked them who took it. Fryberg said that moment “really helped me understand how non-Natives thought about us.”

Experiences like that one ultimately drove Fryberg to study bias and discrimination against Native Americans. She has explored how public representations of Native Americans influence kids’ sense of self and identity development. Identities are social, Fryberg said: “We negotiate who we are with other people.”

Fryberg and her research team’s 2008 study highlighted how Native American mascots have “harmful psychological consequences” for the people they are caricaturing. The researchers found the negative effects of exposure to these mascots may be due, in part, to “the relative absence of more contemporary positive images of American Indians in American society.”

The research included four studies, examining the effects of Native American mascots and other prevalent representations of Native Americans on students’ beliefs about themselves. When students were exposed to common images like Chief Wahoo (of the former Cleveland Indians), Chief Illinwek (of the University of Illinois) and Pocahontas, students generally reported low self-esteem and community worth, as well as little confidence in their ability to achieve their goals. Ultimately, these representations diminished their self-worth.

Invisibility is a reason some Indigenous people hold onto these mascots, Fryberg said: “They’d rather be visible through a mascot than invisible.”

But the mascots can contribute to invisibility, she said, because non-Natives aren’t seeing Native Americans as contemporary people. Instead the mascots show romanticized representations of Native people.

Further research suggested mascots not only affected how Native American kids perceive themselves, but non-Natives’ perceptions of them, as well.

Fryberg has also conducted a review of the existing research on the topic. A 2017 study had found exposure to Native American sports logos increased “negative implicit stereotyping of Native Americans.” Another 2017 study found participants with prejudices rated Native Americans as more aggressive after exposure to relevant sports logos. Those exposed to neutral images did not rate Native Americans as more aggressive.

Fryberg also helped lead the largest scientific study of Native Americans’ perceptions of Native mascots in 2020. It showed Native Americans generally opposed the NFL’s Redskins team name “and the use of Native mascots in general.”

In Marysville, Fryberg said, “at some point, the district needs to hold itself accountable.”

“I mean, it’s pretty clear that Marysville has failed the Native population,” Fryberg said, “and yet it wants to hold on to racist, stereotypic mascots.”

Native American students in Marysville schools have disparately worse test scores than non-Native students.

In fall 2021, only about 6.5% of American Indian/Alaska Native Marysville School District students met the state standards in the math assessment, compared to 17.8% of all students.

“My hope is it will change in the future,” Fryberg said. “My hope is that the district will step up and make those important decisions. There are districts across the country showing that leadership.”

Isabella Breda: 425-339-3192; isabella.breda@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @BredaIsabella.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.