OSO — Nearly five years after a massive mudslide swept across the Stillaguamish Valley, claiming dozens of lives, state geologists still are trying to get a better grasp of the area’s natural hazards.

Mapping and analysis have been ongoing and will be for years to come. It’s an effort not only in Snohomish County but for the entire upper half of Washington, where glaciers carved out similar landscapes.

“There are a lot of questions that need to be answered,” state geologist Dave Norman said. “Why did it move so far? Why did it run out so quickly?”

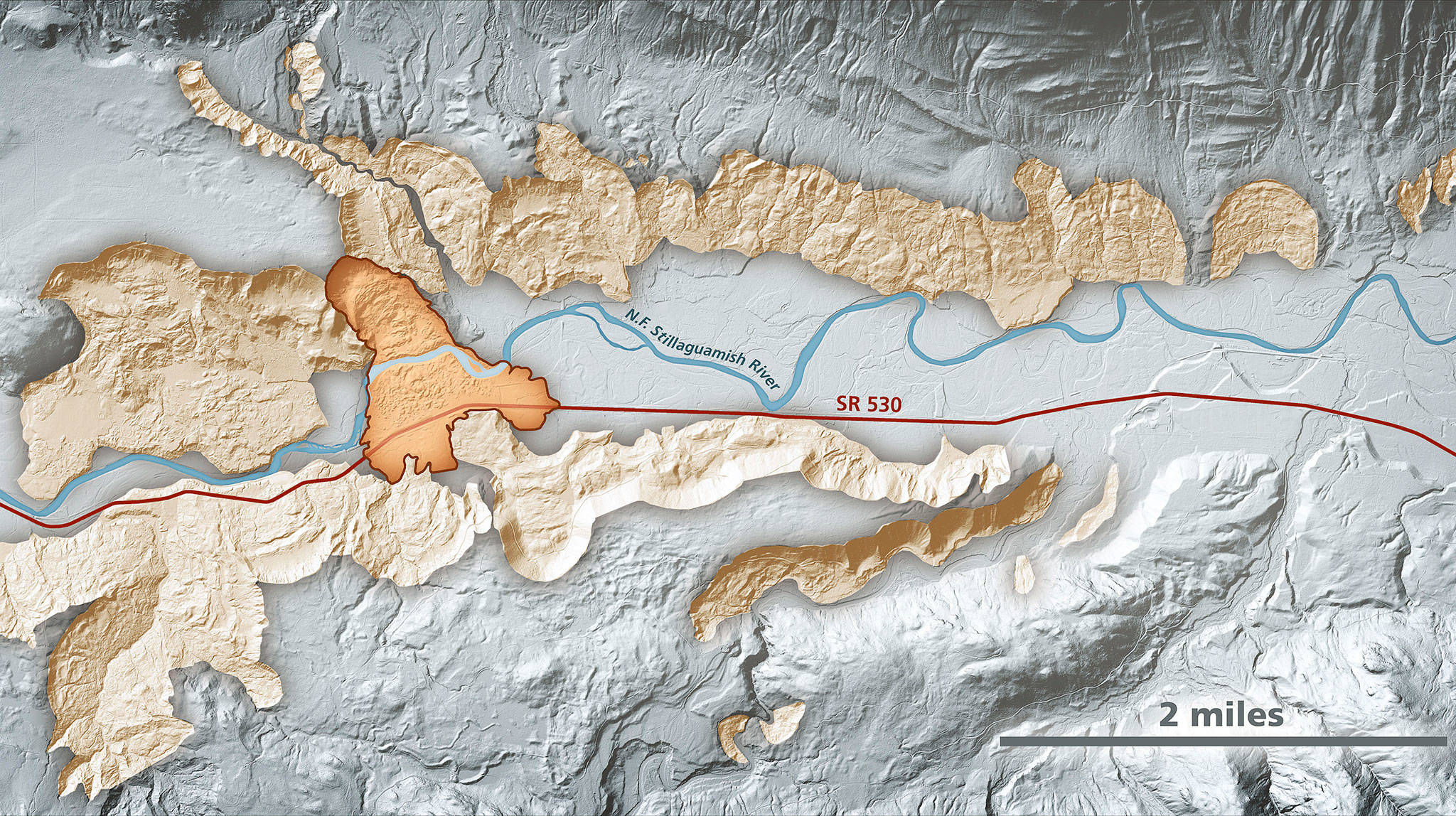

The Department of Natural Resources has requested $1.4 million to study the Highway 530 corridor over the next two years and $1.1 million for the two years after that. The money would pay for two geologists to research, map and monitor the 50-square-mile corridor around the site of the Oso, according to the DNR’s budget request. The research would help scientists figure out how to go about studying landslide risks across 18 counties in northern Washington with similar glacial geology.

Gov. Jay Inslee did not include the money in his recommended 2019-2021 budget. The DNR has put in the same request to state lawmakers, who are working to draft a final spending plan this spring.

The Oso mudslide struck on the morning of March 22, 2014. A hillside collapsed above the North Fork Stillaguamish River, sending earth, water and trees southward. Centered on the Steelhead Haven neighborhood, the slide killed 43 people, took out a stretch of highway and covered a square mile in debris.

The scale of the disaster caught experts and laypeople off guard, though there’s evidence that slopes to either side of the valley have been sliding for thousands of years.

“Just about every major river valley that comes out of the Cascades and flows into the Sound, you have very similar situations as the north fork of the Stillaguamish,” Norman said.

In the aftermath of the deadly slide, Inslee’s office and then-Snohomish County Executive John Lovick convened an expert commission to chart a better course for understanding and reacting to landslide dangers. Among the panel’s recommendations in December 2014 was to “significantly expand data collection and landslide mapping efforts” for landslide hazards.

The highest priority areas included the Everett-Seattle rail line, highways through the Cascade Range and densely populated regions.

The state has made progress, though the program has never received quite as much money as anticipated.

A major tool has been lidar imagery. The three-dimensional maps of the Earth’s surface are created using airplane-mounted lasers. They can reveal features obscured by trees and buildings. In addition to landslides, the images are useful for identifying areas at risk for flooding, tsunamis and other natural disasters, according to the DNR.

“We’ve gathered it all up into one place and one portal,” Norman said. “It wasn’t necessarily publicly available. The portal has been a huge success.”

The DNR’s potential work in the Stillaguamish Valley over the coming years would require boots on the ground, in addition to aerial imagery. Scientists would like to complete more bore-hole testing to better understand the area’s geology, said Stephen Slaughter, the DNR’s landslides hazards program manager.

The DNR continues to release better landslide information for the whole state. In January, the agency published an inventory of 2,838 landslides in King County using new lidar images. Many of those slides were found along Puget Sound bluffs, rivers and mountains, according to a press release. That number doesn’t include smaller landslides, like the kind that block roads after heavy rains.

The state has completed similar landslide inventories for Pierce County and the Columbia Gorge, Slaughter said. The next inventories state geologists expect to complete are for Whatcom and Skagit counties, with Snohomish County likely to follow in 2020.

“We’d like to complete the entire state,” Slaughter said.

Land isn’t static. Norman, the state geologist, said he’d like to have fresh yearly images along the North Fork Stillaguamish River.

“If you do this frequently enough, you can do this as a change analysis,” he said. “That would indicate movement.”

Noah Haglund: 425-339-3465; nhaglund@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @NWhaglund.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.