By Rachel La Corte / Associated Press

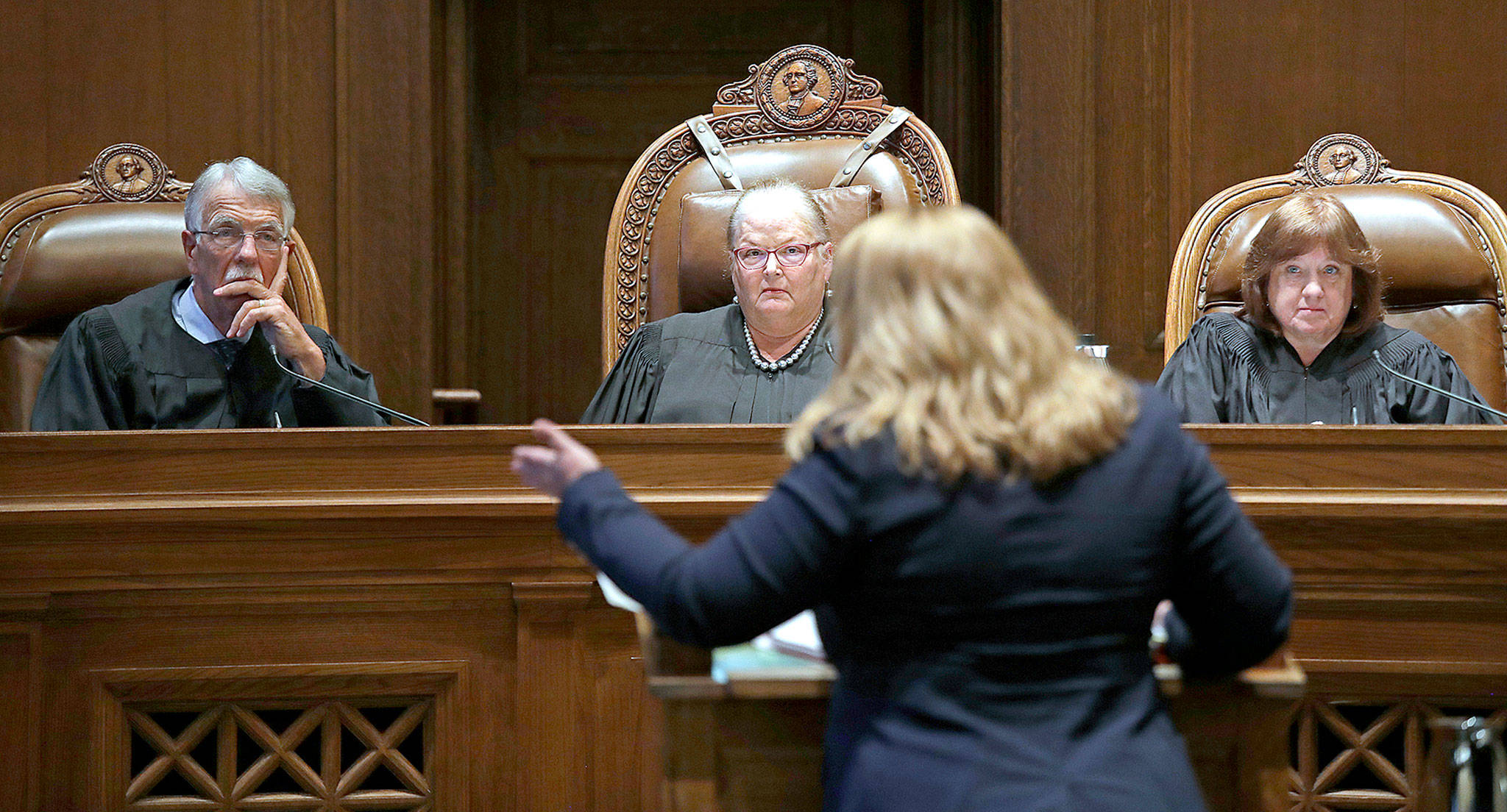

OLYMPIA — Washington Supreme Court justices had pointed questions Tuesday for lawyers representing the Legislature and a media coalition who argued that lawmakers have been violating the law by not releasing emails, daily schedules and written reports of sexual harassment investigations.

The high court heard oral arguments on the appeal of a case that was sparked by a September 2017 lawsuit from a coalition led by The Associated Press and including The Daily Herald and its parent, Sound Publishing. The group sued to challenge lawmakers’ assertion they are not subject to the law that applies to other elected officials and agencies.

A Thurston County superior court judge in January 2018 ruled that the offices of individual lawmakers are in fact subject to the Public Records Act, but that the Washington Legislature, the House and Senate were not.

The media coalition’s lawsuit had named the individual entities of the Legislature, as well as four legislative leaders. The Legislature has appealed the portion of the ruling that applies to the legislative offices, and the media coalition has appealed the portion of the ruling that applies to the Legislature, House and Senate.

The Public Records Act was passed by voter initiative in 1972. The Legislature has made a series of changes in the decades since, and lawyers for the House and Senate have regularly cited a 1995 revision in their denials to reporters seeking records.

The House and Senate currently do release limited records, including lawmaker expenses and per diems.

Attorneys for the Legislature have argued that changes in 2005 and 2007 — when some of the Act’s language and definitions were incorporated into a statute separate from the campaign-finance portions of the original initiative — definitively removed lawmakers from disclosure requirements.

Paul Lawrence, an attorney for the Legislature, said that as of 2007, it was clear that lawmakers were not covered by the law.

“If it was so plain, why didn’t the Legislature just say ‘this doesn’t apply to us’?” Justice Steven Gonzalez asked.

Lawrence said that when the Legislature makes changes to statutes — as it did by only incorporating “state office” into the campaign finance section and not the section of law dealing with disclosure of records — the court must presume those changes were intentional.

“To me it was plain they were saying that, by not incorporating the definitions,” Lawrence said.

Later in the hearing, Justice Susan Owens said she found “it puzzling that there wasn’t as much notice to the public.”

“I don’t recall seeing anything in the paper saying the Legislature exempted themselves from the Public Records Act,” she said. “Did somebody just not pick up on it?”

Lawrence gestured to the media gathered to cover the hearing and said “maybe you should ask the media that’s over there.”

“It wasn’t something that was hidden,” he said.

No bill report, testimony or floor debates on those measures in any of those years indicated that the Legislature’s goal was to exempt legislative records from disclosure.

Michele Earl-Hubbard, the media coalition’s attorney, told the court that voters in 1972 “intended that act to apply to all facets of government.”

She said that the Legislature’s assertion it has amended that interpretation to exclude legislative offices from the law has not been clearly established.

Justice Sheryl Gordon McCloud noted the legislative changes made in 2007 as it relates to the definition for state office.

“What we’re supposed to interpret is what’s on the books now,” she said.

Earl-Hubbard responded that the non-inclusion of a definition doesn’t delete the term itself from the law, and that the court should refer to the definition previously used — which included state legislative offices — since the Legislature never provided a new definition.

“Not once did they say, ‘By the way, by doing this we’re now exempting an entire branch of government,’” Earl-Hubbard said.

Earl-Hubbard also reminded the court of actions the Legislature took following the 2018 superior court ruling, when lawmakers moved quickly to try and circumvent the ruling by passing a bill within 48 hours that retroactively exempted them from the law but would have allowed for more limited legislative disclosure for things like daily calendars and correspondence with lobbyists. After a large public outcry, Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee vetoed the measure.

Another bill was introduced earlier this year that made lawmakers subject to the Public Records Act, with several exceptions, including permanently exempting records ranging from staff analyses to drafts of bills and amendments or records of negotiations among lawmakers. That measure stalled after newspaper executives and media lobbyists blasted it during a public hearing.

“When they mean to remove themselves from the public accountability that the people intended in 1972, they tell us that’s what they’re doing,” Earl-Hubbard said.

The Legislature, which normally would be represented by the attorney general’s office, chose instead to use two private law firms to represent it. The Legislature has spent about $300,000 fighting the case.

The attorney general’s office filed a brief before the high court stating that each lawmaker is fully subject to the public disclosure law, but that the House and Senate are subject in a more limited manner, with the law specifically defining which records must be made available for release by the House and Senate through the offices of the chief clerk and the secretary of the Senate.

Twenty news and open government groups signed on to briefs in support of the media coalition, including the Washington Coalition for Open Government, Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, Reporters Without Borders and the Society of Professional Journalists.

Besides AP and Sound Publishing, the groups involved in the lawsuit are public radio’s Northwest News Network, KING-TV, KIRO-TV, Allied Daily Newspapers of Washington, The Spokesman-Review of Spokane, the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association, Tacoma News Inc. and The Seattle Times.

The Supreme Court could take several months to issue a ruling.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.