EVERETT — Sheriff’s detective Jim Scharf fought back tears on the witness stand Thursday as he recalled the phone call from Parabon NanoLabs.

He’d been walking his dogs on an off-day, when he learned of a breakthrough in the double murder case of a young Canadian couple.

With the help of a genealogist, the lab had found a man whose genetic profile matched DNA from a crime scene.

“What was that name?” the deputy prosecutor asked.

“William Earl Talbott II,” Scharf told the jury in Snohomish County Superior Court.

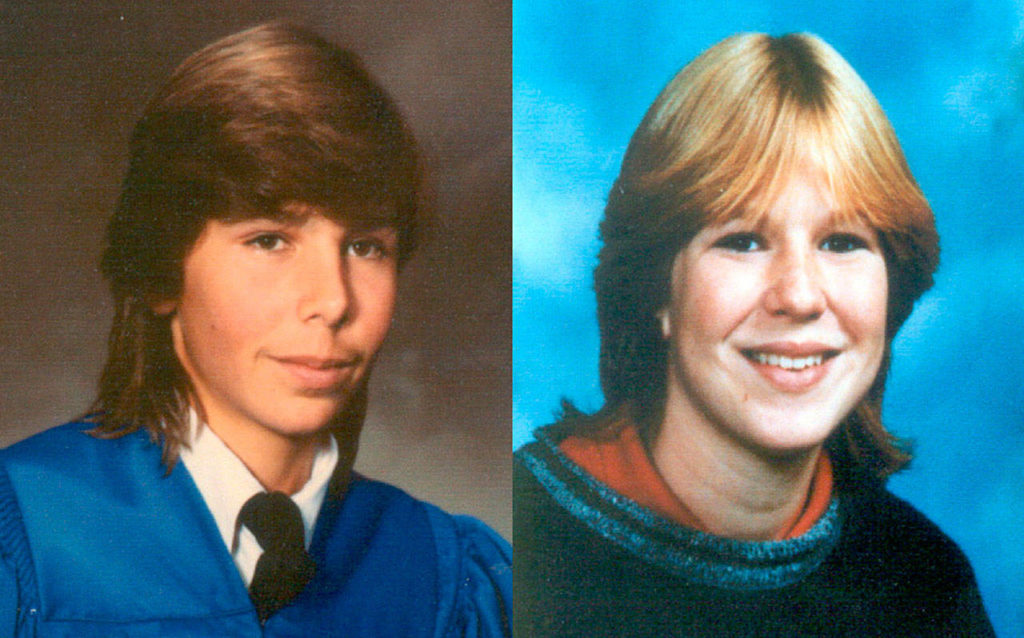

Talbott is now on trial for two counts of aggravated first-degree murder in the killings of Jay Cook, 20, and Tanya Van Cuylenborg, 18.

It was the week of Thanksgiving 1987 when deputies were called to a report of a body in the woods of Skagit County, east of Old Highway 99.

“It was in the fall,” former Skagit County deputy Jim Mowrer said on the witness stand earlier in the week. “So all the leaves had fallen off the trees, and they were on the ground, and it’s a very wet area. Rains a lot up there. And the leaves were wet, and it was hard to see — you couldn’t see — the head or shoulders of the body, because of the leaves and branches.”

Search-and-rescue volunteer Jenny Sheahan-Lee was the same age as Van Cuylenborg, 18, of Saanich, British Columbia, when someone shot the Canadian teen in the back of the head and left her dead in the woods, naked from the waist down.

Cadets combed the brush shoulder to shoulder along Parson Creek Road, in search of a clue that would lead to a killer.

Sheahan-Lee is now a detective sergeant at the Skagit County Sheriff’s Office.

On Thursday she testified that the team had searched for days along the narrow gravel shoulder, and began sifting through undergrowth, when she noticed a .380-caliber shell casing beneath the leaves.

It’s a trial that would not have happened if not for an innovative use of genealogy as a forensic tool. In 2018, a private lab uploaded DNA data from the crime scene to GEDMatch, a public ancestry site where Talbott’s second cousins had shared their genetic profiles, in search of long lost relatives.

Genealogist CeCe Moore built a family tree for the suspect, and her work pointed detectives to Talbott. Later tests confirmed his DNA matched semen on Van Cuylenborg’s clothes, according to prosecutors.

The couple from British Columbia had set out on an overnight trip Nov. 18, 1987, to pick up furnace parts from Gensco, an appliance store in south Seattle.

The sun set around 4:30 p.m.

On the drive south, they missed the exit toward the Hood Canal Bridge. They stopped at a mini mart in Hoodsport, about 30 miles north of Olympia, and bought snack food from the clerk, Judith Stone.

“They wanted to know how much further the bridge was,” Stone testified Thursday.

“Oh, you’re a little past that,” Stone recalled replying. “A long way past that.”

The couple rerouted the Ford Club Wagon van to the Kitsap Peninsula, and pulled over for gas at a deli in Allyn.

Van Cuylenborg had wrinkle lines on her face, like she’d been asleep in the van, testified Kara Hopper, who worked behind the counter at Ben’s Deli. She remembered Cook, too — tall, animated, the only person who ever tried to pay for gas with Canadian traveler’s checks.

As far as police could tell, Hopper was the last known witness to see him alive.

The couple bought a ticket for the Bremerton-Seattle ferry. That boat docked in Seattle just before midnight.

A week later, on Thanksgiving, Scott Walker and a friend were hunting ring-necked pheasants south of Monroe, at the High Bridge over the Snoqualmie River. His bird dog, Tess, rushed into the tall brush beneath the wooden planks of the easterly approach to the bridge. She did not come back right away, and that was not like her.

“She was standing at a distance, I think, trying to figure out what she was looking at,” Walker testified this week. “You could tell she didn’t want to get any closer.”

The hunter saw an ashen-gray human arm in the bushes. He and his hunting buddy reported the body to the nearest Washington State Patrol station.

Former sheriff Rick Bart was a homicide detective at the time. He took photos of Cook’s body, in the fetal position, his face and upper body covered by a blue blanket. He had been strangled with twine and bloodied by a beating. A pack of Camel Lights had been shoved down his throat.

Near High Bridge, detectives also found bloody rocks and hair, as well as zip ties. Those pieces of evidence weren’t discovered until days later.

Zip ties were seized at two other crime scenes in rural Skagit County and downtown Bellingham, where the bronze van was abandoned in a parking lot.

Inside the van were a pair of slacks, with a semen stain on the hem. Over the years, detectives used DNA to rule out possible suspects. But it took 30 years to find a match.

At a break in his testimony, detective Scharf embraced family members of Cook and Van Cuylenborg, who filled the front row of the courthouse gallery.

In letters to the court, longtime friends told a judge last year that the man they knew as Bill Talbott never grew upset, never got in trouble with the law, and it was unimaginable that he could be a killer.

A U.S. Army veteran, 48, wrote he’d spent countless time with his friend, Bill, on motorcycle rides, at barbecues and on camping trips.

“I am very cautious with who I let into my life,” he wrote. “I am cautious with who I let into my families’ lives. Bill became a member of my family.”

Prosecutors expect to rest their case early next week.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.