To speak for trees, Snohomish County activists arm themselves with data

Published 1:30 am Wednesday, July 26, 2023

EVERETT — Some Snohomish County residents have been carrying a checklist while hiking for miles and bushwacking on steep slopes on state lands slated for logging.

What species of trees are there? Are there stumps? Is there a stream? Unusual plants? Signs of wildlife?

Stretching their arms wide and grasping tape measures, they answer a question that is top of mind for companies that would bid to log those properties: What’s the diameter of these trees? Size matters in the timber business. Size matters, too, for these climate-concerned forest surveyors. Because the bigger the tree, scientists say, the more carbon it stores and keeps out of the atmosphere.

The surveys are part of a campaign to get Snohomish County to do what several other west side counties have done: offer to work with the Department of Natural Resources to protect ecologically complex state forests. More urgently, they want the Snohomish County Council to take advantage of Climate Commitment Act funds to put some land off limits to logging.

“We want to help the council do this work,” said Kate Lunceford, of the League of Women Voters of Snohomish County, who is leading the campaign.

This is not work council members are used to doing, or necessarily eager to tackle. They listened quietly when nine activists made their case before recent meetings of the council’s Public Infrastructure and Conservation Committee. County Council members have yet to act on the impassioned public comment and personal visits with activists.

Victoria Tchervenski, a high school student who lives near Brier, asked the County Council in June to “please pause logging on the 6,000 acres of carbon dense, structurally complex, mature forests in the lowlands of Snohomish County.”

Bonny Headley, of Snohomish, shared her conviction that “the trees are more valuable as they stand.” She acknowledged the area’s logging heritage but also mentioned her 6-year-old grandson and concerns for the future.

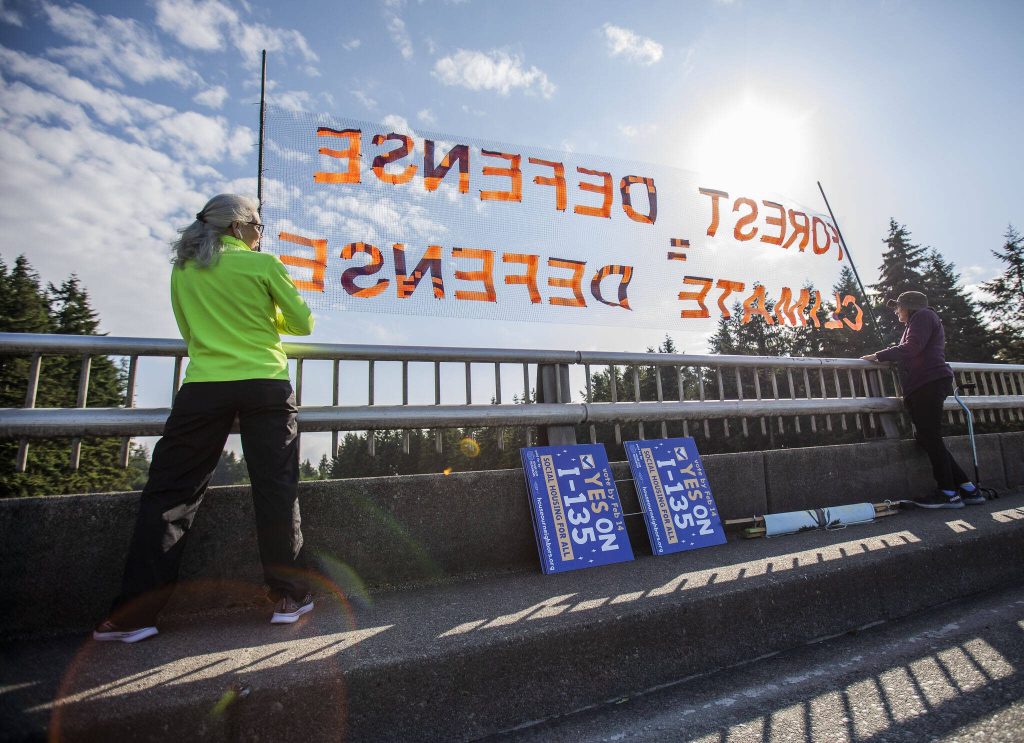

Headley asked the council to join Thurston, Jefferson and Whatcom county officials in writing to Public Lands Commissioner Hilary Franz, offering to work with her to conserve select forest land. Since her testimony, King County Council members jumped into the fray, asking the agency to pause the disputed Wishbone timber sale near Duvall. They want Franz and the DNR board to “work with us to protect the mature legacy forests within this sale area and throughout King County for their climate and biodiversity benefits.”

There are an estimated 77,000 acres of such forests in Western Washington that aren’t already in a conservation area or protected by environmental rules, such as stream buffers. The parcels have been logged but allowed to regenerate naturally rather than be planted with commercially valuable species. This year, the Legislature agreed to permanently conserve 2,000 of those acres, providing money for the DNR to buy younger replacement forests.

Those exact acres haven’t been identified. Competition for climate funds will be keen. Nominations of potentially protected lands can be made starting in August and are due by Dec. 31. They must include letters of county support.

Getting county buy-in

Lunceford and her fellow activists hope to inspire a letter like the one the Whatcom County Council sent in May to Franz and other DNR officials. It asks the state to consult with the county, tribes and other stakeholders regarding stewardship of state lands. The county, the letter notes, isn’t even consulted when the state logs county-owned trust land. The letter also expresses support for legislative-supported forest protection programs.

The Whatcom County letter opens with a statement of support for the timber industry. That subject is top of mind for Snohomish County Council member Sam Low. He represents heavily forested eastern parts of the county.

“Snohomish County is 1.3 million acres total, about 1 million acres are trees, and two-thirds of that is already protected federal or state forest land,” he said. “Wood has to come from somewhere.”

Low is wary of promises to replace lost timber proceeds and dismissive of the words that activists use to describe not-quite-old-growth forests.

“There’s lots of ‘legacy’ forest already protected, if you want to use their terminology. The language changes, the methods change — it is still pulling more timber out of production,” he said. “There aren’t many mills still open, and even those that are open are struggling to get timber.”

In 2021, the Snohomish County timber industry supported 6,013 jobs, according to the Washington Forest Protection Association. There are 385,126 acres available for harvest. Most of it is private land, the source of 70% of Washington’s timber.

Low recalled an unsuccessful effort to stop the 2022 Middle May timber sale near Gold Bar and Wallace Falls State Park. On a 3-2 vote, the County Council passed a resolution supporting the sale’s progress as soon as possible. Low, a Republican, voted for it. Democrat Megan Dunn voted no, believing it was against the wishes of residents concerned about the impact on the environment and recreation.

Still, Dunn expressed reluctance to jump into the latest state forest fray.

“The issue of the council working directly with DNR is brand new. That is not a relationship we’ve had before. That’s why we’re resistant to act,” Dunn said. “And it would undermine the tribes if we were to act without their support.”

In the Whatcom County letter, council members asked the DNR to pause logging plans for the Brokedown Palace sale along the Middle Fork Nooksack River until it could be evaluated for inclusion in the state Climate Commitment Act program, or two other programs that would protect it. One is Franz’s new carbon project, which will lease land for carbon sequestration and storage. Another is Trust Land Transfer, in which DNR-managed forests with high ecological or public benefits go to a receiving agency such as local government, tribe or state parks. In return, the DNR gets money to buy income-generating land.

The Snohomish County activists pinned hopes on using Trust Land Transfer to prevent the 138-acre Hog Wild timber sale, north of the Sultan River. While county support to pause the sale wasn’t required, the activists sought it. No dice. The trees will be auctioned Aug. 30, for the benefit of the Sultan School District.

Into the woods

With the end-of-year application deadline looming for the Climate Commitment Act funding, the activists are hustling, eager to identify and propose three planned timber sale parcels worthy of the program.

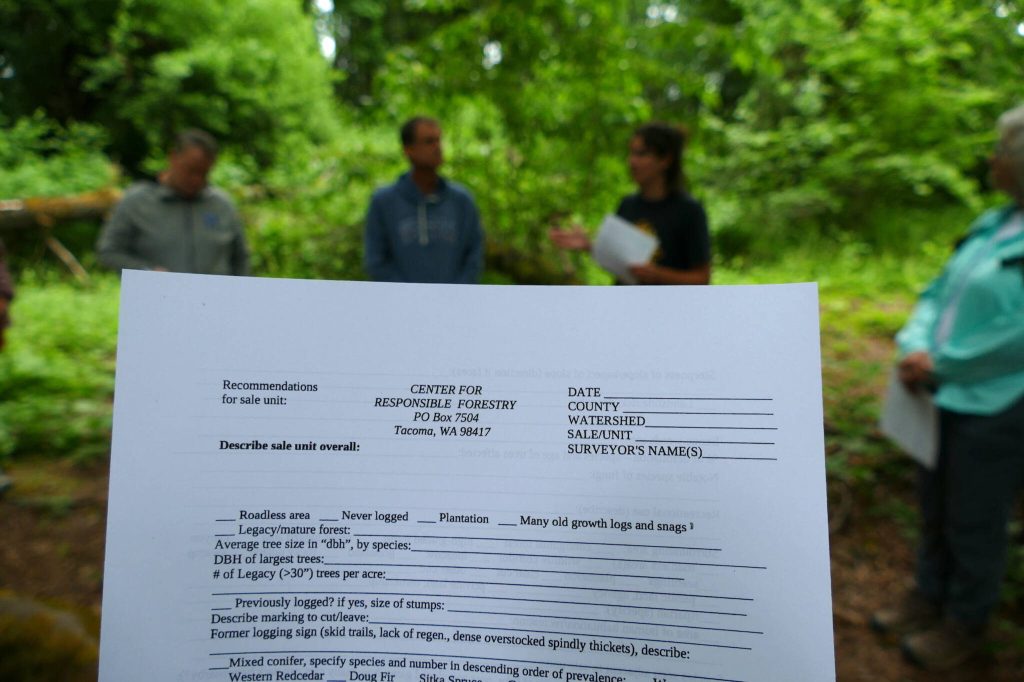

The nonprofit Center for Responsible Forestry is helping. North Sound Regional Coordinator Carly Lloyd told volunteers at a recent survey training session that the DNR doesn’t document the diversity of life in its mature stands before selling the timber. To fill the void, the center created a checklist — the white printed sheets the volunteers were clutching. They were standing in the formerly logged North Creek Forest. The Bothell-owned land has characteristics of some sites destined for state logging.

On the prowl to identify species, the volunteers wrote down plants both native and invasive, ticking off blackberries, Oregon grape, devil’s club, maples and many more. They sometimes used plant identification apps to double-check their guesses.

“Sedges have ledges,” someone reminded. They discussed the habitat value of standing dead trees and pointed out decaying “nurse logs” that nurture rows of saplings.

Lloyd, a Western Washington University student and former volunteer surveyor, called the training session “a reminder of how fun it is to be in the forest.”

She is motivated by the impact of climate change.

“Personally, it’s the main reason I’m doing this,” Lloyd said. “Forests are the biggest life-holders in this region and a backbone for the Salish Sea.”

Among the volunteers-in-training were Tchervenski and other members of the Climate Action Club at Bothell’s Innovation Lab High School. Lunceford has recruited students for their stamina and enthusiasm. Reaching remote state forests often involves long hikes past locked gates — while the land is open to the public, roads are often closed. Lunceford laments the agency’s frequent unwillingness to share keys.

“The fact that DNR is making it much more difficult to get through any of these gates is an indication that it recognizes there is a lot of advocacy going on and they don’t want people to advocate for these forests,” she said.

Kenny Ocker, communications manager for DNR, said there are several reasons the gates are locked. A road may be an easement on someone else’s land, or the state’s property has been abused or subject to timber theft. Staff may be unavailable to help.

“We leave as much stuff open as we can,” he said.

Of the 157,000 acres the state manages in Snohomish County, only half is available for forest management, Ocker said.

DNR faces dueling legal mandates of making money off public lands for public benefit, while also protecting the environment.

“We are at a very interesting spot in the land management landscape,” Ocker said.

Voices for change

Lunceford is well known among local government officials for her efforts to protect urban trees. This year, she helped convince the state League of Women Voters to pass a resolution in May demanding “that action be taken now to ensure the protection and conservation of all remaining mature and old growth forests on public lands in Washington State.” It echoed a stand taken by the national organization in 2022.

Established environmental groups have long lobbied to stop logging, or at least improve logging practices, on state lands west of the Cascade Crest. The consequences of climate change — heat waves, floods, intense storms — are ratcheting up concern. Advocates were heartened in 2022 when the Washington Supreme Court ruled the DNR can manage lands for diverse public interests, beyond maximizing revenue.

The three-year-old Center for Responsible Forestry focuses exclusively on protecting ecologically complex state forests. Its founder, Steven Kropp, left it to create another organization with the same mission, the Legacy Forest Defense Coalition. On June 27, five protesters of another new group, the Lorax Coalition, locked themselves together in the DNR rotunda in Olympia until they got a meeting with a senior official and members of the media. The Lorax is a Dr. Suess character who fights environmental destruction.

Some influential people are speaking out. Peter Goldmark, board chairman for the Center for Responsible Forestry, is a former state lands commissioner. Along with his DNR predecessor Jennifer Belcher, he has proposed phasing out logging on state lands in Western Washington. Once tasked by state law with overseeing logging, both now cite the climate crisis as a reason to end the practice.

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Chris Reykdal shares their view, even though school districts are the biggest beneficiaries of state logging. The Middle May timber sale, for example, paid for a new roof on Sultan Middle School, Ocker said.

Reykdal noted timber proceeds are “an almost invisible share” of what is spent each year on school buildings. According to his office, only 1% of the nearly $3.2 billion in state and local dollars spent on K-12 construction in 2022 came from DNR sales.

“I believe that school construction, like operating a school, is a basic education right of kids … it should never be a function of whether you have trees in your backyard, or some disease or fire affects logging,” Reykdal said. He added that any timber revenue “should fund forest health, clean water, and definitely go back to supporting timber communities.”

Reykdal said he’s always felt that that way. With climate change, he said, “maybe I’m doubling down.”

Julie Titone: julietitone@icloud.com; Twitter: @julietitone.

Julie Titone is a freelance writer who reports on climate change for The Daily Herald. Her journalism is supported by The Herald’s Environmental and Climate Reporting Fund. Learn more and donate: heraldnet.com/climate-fund.