MARYSVILLE — When twin sisters Alissa and Kelsey Edge found out that Lushootseed language classes were being taught at Marysville Pilchuck High School this year, they had to sign up.

The high school seniors saw it as a way to learn more about their heritage. They’re members of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe.

“We wanted to become closer to our culture and make sure the language doesn’t die,” 18-year-old Alissa said.

Lushootseed is a traditional language spoken by Coast Salish tribes along the shores of the Puget Sound. The Marysville School District and the Tulalip Lushootseed Language Department partnered this year to bring the classes to the high school.

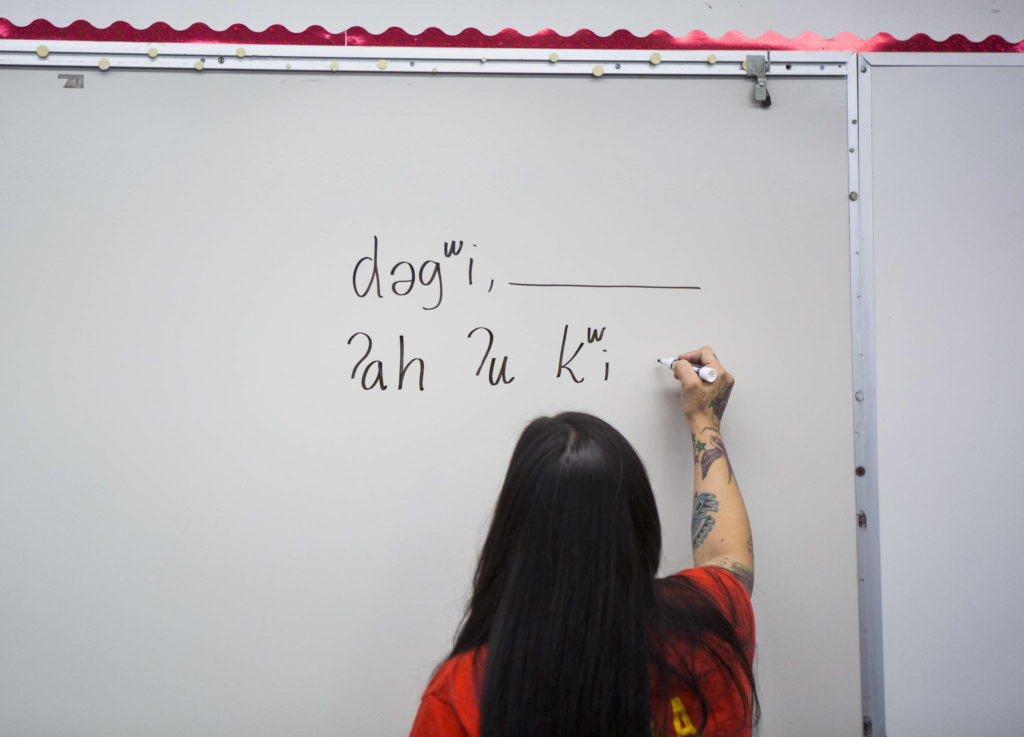

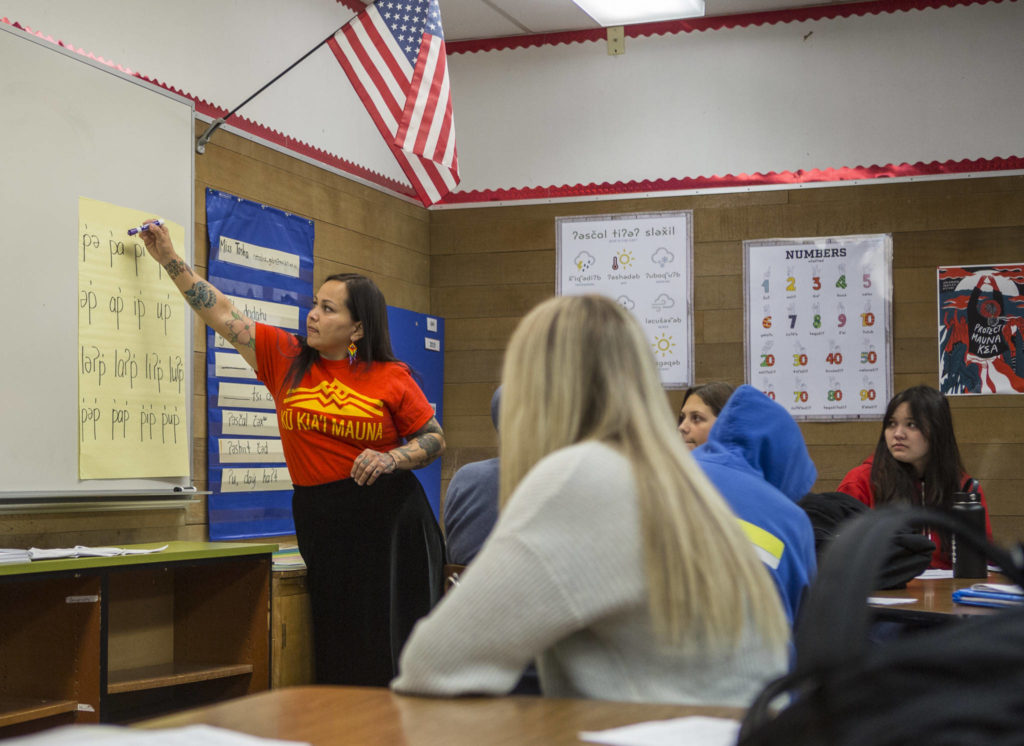

Instructor Natosha Gobin teaches two classes at Marysville Pilchuck, open to all students. It’s the first time in decades the language has been offered there.

Other schools in the district that teach Lushootseed include Heritage High School and Quil Ceda Tulalip Elementary School. About 190 students in Marysville schools are learning the language.

For generations Lushootseed has been disappearing. One reason is because of government boarding schools in the 1800s and 1900s, where Native American children were sent for cultural assimilation, a failed U.S. government policy to take them from their families to mainstream them into American life. Many were beaten for speaking their native languages. A motto at the time was: “Kill the Indian and save the man.”

The schools were all over the country, including on the Tulalip Indian Reservation.

“It’s such a big part of the history here,” Gobin said. “The Tulalip Boarding School was right here, right on our lands, right in the bay. There’s remnants of the traumatic places. The generational trauma, it’s a real thing, and it still affects people.”

She hopes the classes inspire young people to bring the language back into their homes and speak it with others.

Alissa and Kelsey, for instance, have been talking with friends from Gobin’s class when they see each other around campus. They’ve also been speaking it with their older brother, who’s learning Lushootseed at the University of Washington.

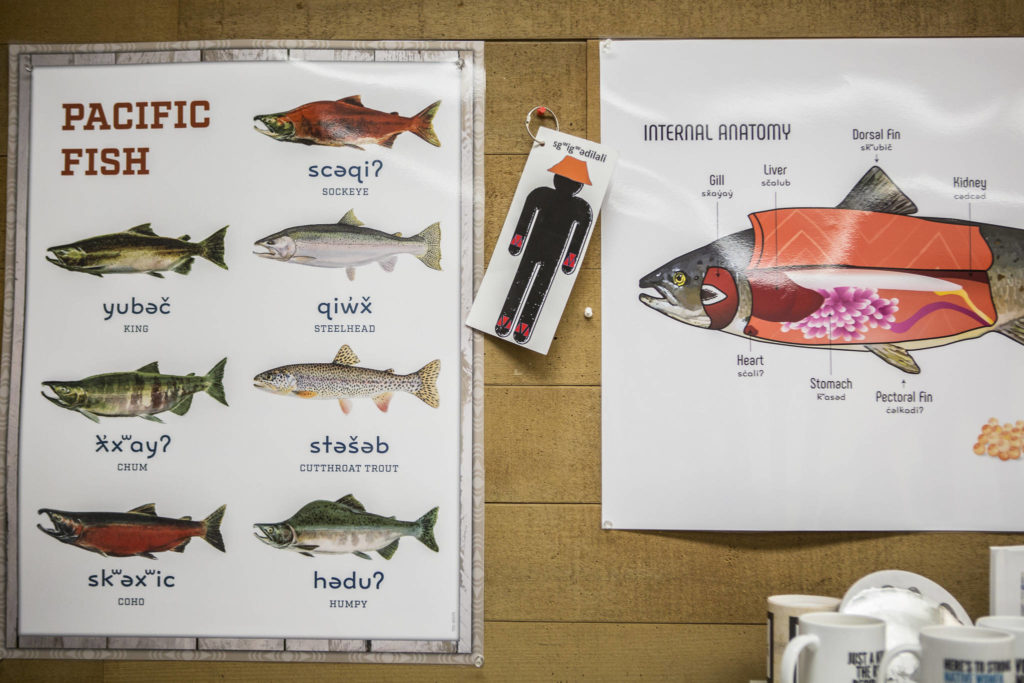

Inside Gobin’s classroom, handwritten words on yellow sheets of paper line the walls. Other posters show the Lushootseed words for numbers, emotions and different kinds of salmon.

On a Friday morning, the day after Halloween, Alissa and Kelsey joined their friends in their second period class. Laughter filled the room as they practiced the language of their ancestors over games of Trouble and Go Fish.

Tulalip Boarding School

The government-run Tulalip Boarding School opened in 1901.

As a child, the late Harriette Shelton Williams Dover was sent to the school. Her father was William Shelton, a leader in Tulalip who was known for his storytelling and carving.

Dover became the second woman ever elected to the Tulalip Tribes Board of Directors, and was the first council chairwoman. She died in 1991 at the age of 86.

Other boarding schools in Washington were in Neah Bay and Puyallup. Children sent there were removed from their families and cultural traditions, and punished when they spoke their native languages.

“The discipline was to civilize us,” Dover has written.

She was 7 when she arrived at the boarding school in 1912. She’s described the school as a penitentiary with military-style training and schedules.

Students stayed at the school for 10 months of the year. Some died from illnesses there, including Dover’s sister who developed tuberculosis.

Once the children got to the school they were expected to only speak English, and learned it while they were there.

Dover had a memory from a time when she was 9, and one of the teachers found out she and a friend had been speaking to each other in Lushootseed.

“The matron strapped us from the backs of our necks all the way to our ankles for talking in our own language,” Dover wrote. “She made that strap sing around my neck, and she nearly knocked me out.”

Later, she found out those kinds of whips had been used in prisons and eventually were outlawed because of the harm they caused.

She never spoke Lushootseed at the school again. She graduated in 1921. It closed about a decade later.

In later life, Dover led efforts to save her native language and cultural traditions taken from her before the words and old ways would be lost forever.

‘Healing what was stolen’

After coming home from the boarding schools, many were afraid to teach the language to their children, including Chelsea Craig’s grandmother.

“She died thinking it was wrong to speak her language,” Craig said.

Craig is a cultural specialist at Quil Ceda Tulalip and has worked for the Marysville School District for almost 20 years.

Craig’s grandmother learned Lushootseed as her first language. She stopped speaking it after being sent to the school.

“She experienced cultural genocide from the first introduction of formal education,” Craig said. “That same oppression has passed on from generation to generation. The work that is happening now is interrupting the system of oppression for our people. It’s beyond offering a class. It’s healing what was stolen from my family.”

Craig grew up in Tulalip and attended Marysville Pilchuck, where her children are now students. Her son is in Gobin’s class.

Back then, she was one of the only students who was a tribal member. She often felt she had to leave her culture behind when she came to school.

“It wasn’t a safe place to be indigenous where you were from,” she said. “By setting this precedent, not only is it OK, but it’s embraced.”

Deborah Parker attended Marysville Pilchuck around the same time. She’s now director of equity, diversity and indigenous education for the district.

She visited Gobin’s class on the first day of the school year. She had to leave the room at times to let herself cry as the students learned about her ancestors.

“To have our children to be able to come to school and learn something that is deeply rooted within them, that was one of my favorite days here at work,” she said.

She’s happy to have the Lushootseed classes at Marysville Pilchuck, but hopes to see more indigenous representation in the district. She’d like for more teachers to be hired from the Tulalip Tribes. At the moment, there are two, she said.

She and Craig agree, this kind of class would have been important to them.

“It would have meant everything,” Craig said.

Preserving the language

The Tulalip Lushootseed Language Department was started in the early 1990s. Today’s teachers of the language are grateful to those who had the foresight to preserve the words before they were lost.

There were many who sensed the urgency, including Dover, the late Hank Gobin and others on and off the Tulalip reservation. A team of linguists with University of Washington professor Thom Hess and an Upper Skagit elder named Vi Hilbert spent decades dedicated to saving precious fragments of the past so today’s generation of students can speak it and pass it on.

In all, there are about 90 teachers in the program. They offer Lushootseed classes, including at the Northwest Indian College, the Tulalip Early Learning Academy and now in Marysville schools.

Quil Ceda Tulalip was the first to incorporate Lushootseed lessons.

Maria Martin and Nik-ko-te St. Onge have been teaching the same group of children for about seven years. They started teaching the kids in the tribes’ early learning program, followed them into kindergarten and have moved up with them every year since. Now, the class is in fourth grade.

“We are practically their aunties, we’re all so close,” Martin said.

Whenever the children see their teachers, they run up to hug them.

The pair hope to continue teaching the kids into middle school, but that plan isn’t certain yet.

In the beginning, most students didn’t know much of the language. Now they can read Lushootseed, even if they don’t know what it means. Sometimes they even point out their teachers’ mistakes.

“I’ll mess up my spelling or something and they’ll correct me,” St. Onge said. “I always think that’s cool, like, they know. And they’re not afraid to call me out.”

Some of their students speak Lushootseed in tribal ceremonies, and others have found out more about their relatives through the classes.

Martin hopes the children continue to learn and use the language.

“There’s so much in Lushootseed you can say that can’t be translated into English,” she said. “There’s a different thought process when you are speaking Lushootseed, and that’s really special to our people. I would love to have our kids have that within themselves, too.”

Michelle Myles has taught Lushootseed at Heritage High School for about three years. She hopes more families begin to speak it at home, as she does with her own. That’s starting to happen now between high schoolers who take the classes and their younger siblings in elementary school.

The teens have asked Myles for phrases they can use with their friends, such as “What’s up, dog?” While it may not be grammatically correct, she teaches them.

“If you give them enough to own it, they’ll say it,” she said. “That’s just how it starts, and it’s great. It’s really great.”

Spreading the words

Matt Remle had been working for years to bring Lushootseed to students at Marysville Pilchuck. He’s the school’s lead native liaison.

He tried to get Running Start students to classes through the Northwest Indian College, but it didn’t work very well because of scheduling.

He asked Myles about the program at Heritage, and how they could start one at Marysville Pilchuck. After, he brought the idea to former principal Dave Rose.

Rose left that position at the end of last year, so the conversation continued with current principal Christine Bromley. She was immediately on board.

Of 1,200 students at the school, 143 identify as Native American, she said.

“That doesn’t mean they are all Tulalip, but it is so much a part of our school, and I want to celebrate and reinforce that,” she said.

She hopes to make the school a place where students can see themselves.

At first they offered one Lushootseed class, but 60 people signed up. They added another.

Bromley plans to open a more advanced class next year so the language counts toward college. Most universities require applicants to take two years of the same language during high school.

Remle would like to give those at Marysville Getchell High School a chance to take the class, as well. Next year, he hopes students can visit Marysville Pilchuck during those times.

Making Lushootseed available at Totem Middle School is in the works, too. Most kids who live in Tulalip end up moving there from Quil Ceda Tulalip.

“If we get that established along with the Getchell class, not every school would be covered, but at least the majority populations of tribal students would be,” Remle said.

‘The language is still alive’

Gobin first started out in the Lushootseed department by volunteering in the program’s language camps while she was still a student at Marysville Pilchuck.

“I quickly fell in love with it,” she said. “I haven’t tried to pursue anything else since. I feel lucky and blessed that I found my place at such a young age.”

Soon after she graduated, about 19 years ago, she was hired by the department and has been teaching ever since.

She remembers a Lushootseed class being taught at Marysville Pilchuck briefly around that time, but it hasn’t been available since.

In September, Gobin started to teach at her former high school.

It’s still new to the students, and she sometimes has to remind them why they signed up for the class.

“We do a lot of culture, talking about lineage and trying to get them to feel connected with the language,” she said.

She encourages students who are not Native American to learn more about their own family if they’d like, or to honor other heritages in the room.

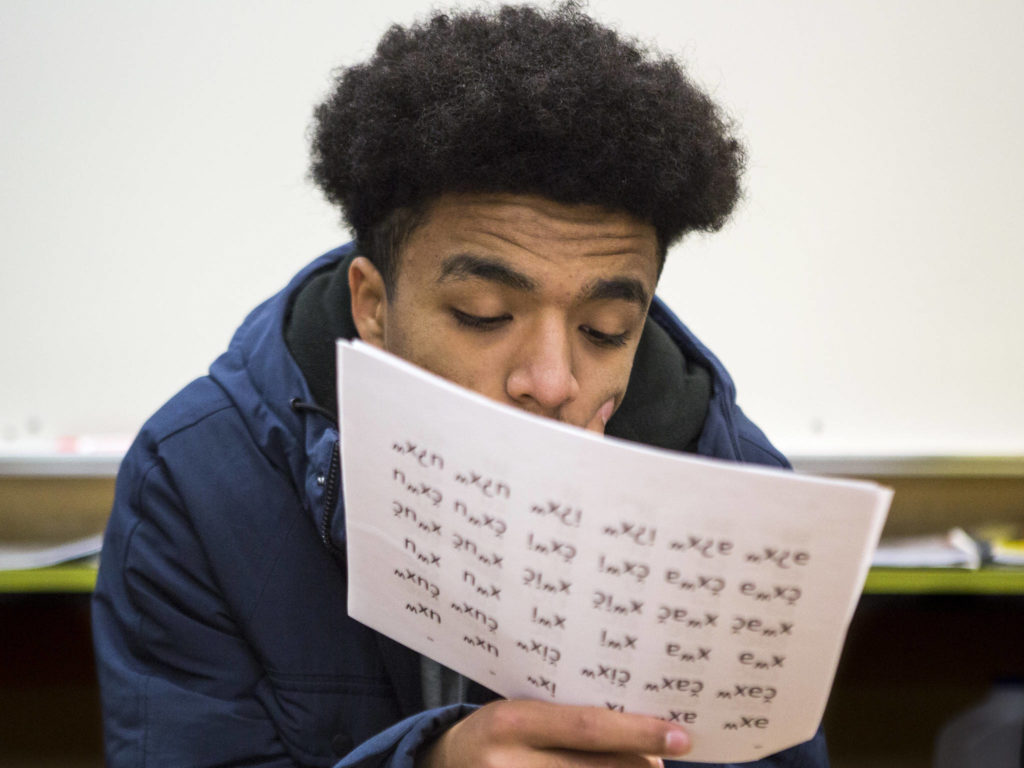

Kamiakin Craig, 17, signed up for the class to continue the language of his ancestors. His sisters also are teachers in the Lushootseed department, and his mother is Chelsea Craig, the cultural specialist at Quil Ceda Tulalip.

“I think it’s important to learn the language my people have lost,” he said. “When my ancestors used to speak the language it was normal for them. Eventually they lost it because of boarding schools. Over time we lost it.”

This is the first time he’s taken Lushootseed. He looks forward to the class every day, where he learns about elders and others who come from his tribe.

Craig is a senior, and next year hopes to attend either Everett Community College or a four-year university. He plans to become an educator, like both of his parents, and thinks he might want to teach Lushootseed someday.

That’s one of Gobin’s goals. She hopes the students continue to spread the language outside of the classroom.

“As soon as we walk out that door, the language is still alive within us,” she said. “We have to honor it, and we have to use it.”

Stephanie Davey: 425-339-3192; sdavey@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @stephrdavey.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.