Editor’s note: This is the third in a series of three stories about the history and lingering trauma of the federal Tulalip Indian School, as well as other regional boarding schools attended by Tulalip children.

TULALIP — In Lushootseed, an “s” with a squiggle above it is called a caron. It’s pronounced “sh,” like shore or shout.

Pišpiš means “cat.” It’s one of the first words Kaiser Moses learned with his Montessori classmates on the old wooden floor of the Tulalip Dining Hall. The refurbished early 20th century building sits above the rocky shore of Tulalip Bay. Outside the window, saltwater waves lap against concrete rubble.

Years later, Moses learned those are the ruins of a jail.

“And that’s where they used to put kids who spoke Lushootseed instead of English,” said Moses, 19.

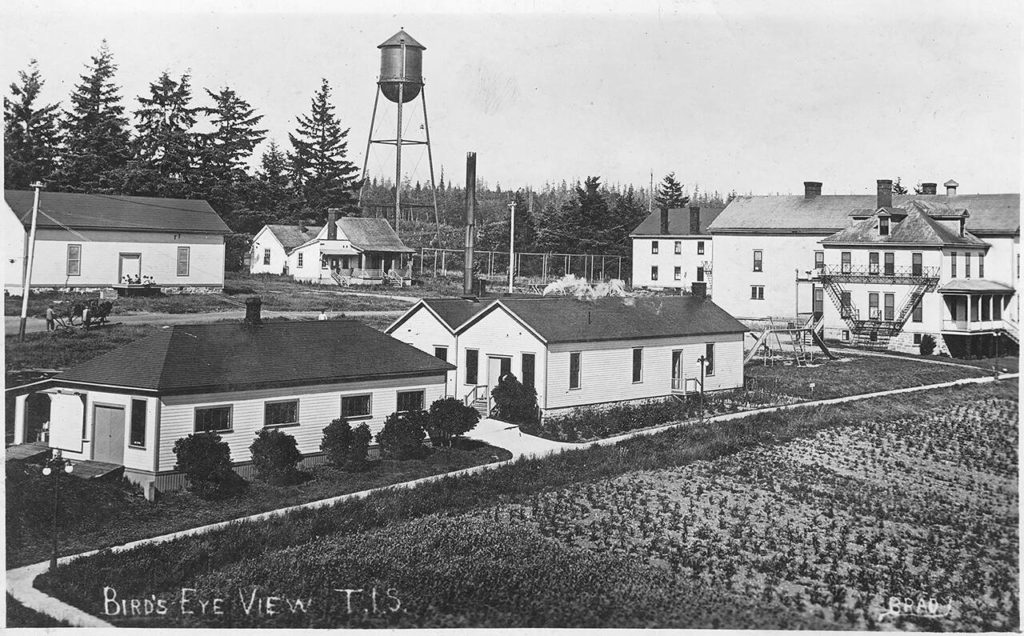

The graffiti-covered ruins and the renovated dining hall are among the few physical reminders of the Tulalip Indian School. For seven decades, the federal government funded or ran a boarding school here. It was one of hundreds of institutions where children were torn from their parents and forced to give up traditional ways of life: their language, their family songs, their Native dress and anything considered “Indian.”

It was one of hundreds of institutions where teachers “deployed systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies” on Native students to “kill the Indian in (them), and save the man,” according to a national report released by the U.S. Department of the Interior in May.

At Tulalip, thousands of children from around the Pacific Northwest endured forced labor, malnourishment and physical abuse. The campus shuttered in 1932. For many families, the trauma has rippled across generations to the present day. Healing has been arduous and, at times, impossible.

Now, many descendants of former boarding school students are again growing up immersed in Native culture: rediscovering old ways of carving, weaving and storytelling; rekindling Coast Salish traditions; and resurrecting the once-illegal Native language Lushootseed.

Not long ago, in the building where Moses received his Lushootseed lessons, school officials locked children in the basement for days for speaking it.

‘A lack of visible love’

As a little girl, Dr. Stephanie Fryberg sat outside the room as her grandmother Rose Fryberg spoke with other survivors of the boarding school era. She could hear the elders through the open door — she learned a lot.

Rose Fryberg died in 1995.

“It was a lot of trauma inflicted upon them, like physical abuse,” said Stephanie Fryberg, a 1989 graduate of Marysville Pilchuck High School, now a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan specializing in trauma and Native American identity. “I’ve heard lots of stories around Tulalip about the sexual abuse that was experienced, and then I’ve heard some really awful stories about how the father of the school would sexually abuse the children, and ended each time by saying, ‘This is love.’”

Other families heard stories like this. But none of the leaders of the Tulalip school were charged with crimes.

Many Indigenous people inherited their ancestors’ pain.

“It had really disturbing resonances, and we know those behaviors have been passed on — a lot of the physical abuse and sexual abuse,” Fryberg said. “And we talk a lot as a community about, ‘What does it really mean to heal?’ I mean, how do you hold people accountable for something terrible that happened to them? But if they’re doing it to someone else, at some point, you have to figure out how to stop the cycle of trauma. And you don’t do that by giving up on a whole generation.”

In the Pacific Northwest and across the country, laws required generations of Native children to grow up in the schools under strict matrons and teachers, separated from their parents for 10 months a year. According to the Interior report, the U.S. government viewed the disruption of the Native American family as essential for assimilation.

“There’s no sense of what it means to grow up in a loving, safe and warm environment,” Stephanie Fryberg said. “So then, what do you learn about parenting? If you don’t do something right, you get your hand slapped, like — you must be punished.”

In a survey of 22,602 First Nations people, over 70% of respondents said they felt their grandparents’ attendance at a boarding school negatively affected their parents’ upbringing.

“People on the reservation lost all parenting skills, lost their kids, their language and their culture,” said Teri Gobin, chairwoman of the Tulalip Tribes. “… Totally, it was trying to annihilate a generation.”

Gobin, 64, said her father always cared for her, but he had trouble saying the words “I love you.”

Terry Fast Horse, 52, a Tulalip resident of Lummi and Lakota descent, said he has a good relationship with his mother, a survivor of the Marty Indian School in South Dakota. But it took years to build it.

“In years past there has been a lack of visible love between us that we have at the dinner table, (or) any time, any gatherings,” he said.

Students could be reprimanded for speaking to their siblings in the school, or attempting to go home, Fast Horse said. They didn’t learn how to connect with family.

Kaiser Moses’ grandmother Theresa Moses attended a boarding school on Vancouver Island. She rarely talked about it with her kids. All Moses knows, he said, is that she caught tuberculosis there.

Bonnie Sanchez, a Squaxin Island tribal elder, said the Chemawa Indian School damaged her mother “in a lot of ways.” The school, near Salem, Oregon, left her mother with “no parenting skills,” said Sanchez, 60.

“And so that’s part of why I was raised by her father and her stepmother,” she said. “She did not learn parenting skills or nurturing, and it affected my sister and I immensely.”

A 2019 study found Indigenous people raised by boarding school survivors suffered far more traumatic events in childhood, compared to those with parents who did not attend the schools.

John Campbell, 75, said his mother, a Tulalip Indian School survivor, used to wash out his mouth with soap if he cursed.

“I think she learned that from the boarding school,” said Campbell, a Tulalip elder.

It was a common punishment for speaking Lushootseed.

Campbell’s father, who attended Chemawa Indian School, was often agitated by his kids’ “bad” manners. At the school, his father said, students would get stabbed with a fork if they tried to reach across the table.

Often boarding school survivors tried to subdue their trauma by self-medicating with drugs or alcohol. And then, often, so did their children.

‘Until we heal our spirit’

Steven Iron Wing II first tried cocaine in the late ’80s with his father, a survivor of the St. Francis Indian School. Many of Iron Wing’s earliest memories of his dad involve “a lot of alcoholism.”

“That was what he introduced me to,” he said. “Being an actual father wasn’t something I ever was taught.”

After his father died in 2008, Iron Wing, 54, came across an article about what children lived through in the South Dakota boarding schools, “you know, equating to sexual and physical abuse.”

“And then as I learned more about boarding school systems when I was working on my bachelor’s degree,” Iron Wing said, “it kind of all came together for me. It clicked. … It’s kind of like I didn’t really understand him until after he died. I was finally able to actually forgive him for decades of neglect.”

Now a licensed chemical dependency professional, Iron Wing manages the Tulalip Tribes’ Stanwood Healing Lodge, a refuge for people to readjust to society after inpatient treatment. It’s open to anyone enrolled in a federally recognized tribe. Iron Wing helps others to confront an underlying reason they’re hurting: Boarding schools dismantled their families and culture.

“If you don’t know why you’re doing something, and it’s ingrained in you, how can you fix it?” he said.

Learning the history of “language and culture loss — or even abuse experienced at boarding school — within the historical facts of colonization can provide profound psychological relief,” according to a study published in the AMA Journal of Ethics in 2021.

“The latest research on specifically Indigenous historical trauma finds that its effects are wide-ranging — from historical loss that brings feelings of shame and anger as well as drug and alcohol use to suicidality, sexual abuse, and depression among residential school survivors,” concludes the study from the University of Colorado Boulder. “Historical loss is complex because it denotes the loss of land in addition to loss of culture.”

Traditional painting, woodworking, making ribbon skirts, building drums and beating drums are core parts of the healing at the Tulalip lodge, Iron Wing said.

Hundreds of tribal members have received help through the tribes’ substance use disorder program. The Tulalip Tribes also offer free counseling, free job training courses and transitional cottages — all funded by gaming revenue and grants, with the aim of helping tribal members to find stability.

“We have some beautiful programs here in Tulalip,” the tribes’ Chief Administrative Officer Rochelle Lubbers said. “But so many of them are band-aids until we heal our spirit.”

‘Keep your Indian alive’

As she thumbed through a 2-inch-thick spiralbound picturebook, Tulalip elder Diane Janes stopped on a page with a school worksheet dated April 18, 1973. Photos show longtime Tulalip leader Scho-Hallam, also known as Stan Jones Sr., in a showy blue jacket adorned with ribbons of tiny cedar paddles, stretching his arms wide, beating a circular drum. The images are overlaid on a typewritten Lushootseed worksheet.

1. Welcome to a white person. Oh-hotl’-tuo’lochee-lutz uteee’a pos’tud.

2. Sit down here. Ah-tee oh-quats gwa’-deal.

Jones, a descendant of the Snohomish and other Coast Salish tribes, lived at the Cushman Indian Hospital in Tacoma from age 9 to 12. The compound doubled as a school, and “Jones says assimilation into white culture carried on there too,” according to interviews with a historian.

For speaking Lushootseed, he wrote in his autobiography, “I remember having my mouth washed with lye soap; my tongue dried up so bad, it cracked and split open and bled.”

Jones, who died in 2019, led an extraordinary life. He was among 44,000 Native Americans who fought in World War II. He occupied Nagasaki, still “frizzling like a baked apple,” in the aftermath of the atomic bomb, as one biographer wrote. In Japan, he learned to speak more Japanese than he could Lushootseed. Back home, he fought for tribal fishing rights that were won in the historic Boldt decision and helped to grow the Tulalip payroll from three to 3,500 employees while serving as a tribal board member for 44 years. Over half of that time he served as tribal chair.

And at age 46, Jones studied Lushootseed in the early days of a cultural revival.

“It is important to carry on your language: keep your Indian alive,” said Jones, in a quote attached to Janes’ worksheet. “Your grandparents were punished for speaking the Indian language in the government schools they were forced into at five years old: goal to destroy the Indian.”

The official federal policy on Native language suppression can be traced to 1868, when General Ulysses S. Grant commissioned a report on how to end the Indian Wars.

“Through sameness of language is produced sameness of sentiment, and thought; customs and habits are molded and assimilated in the same way, and thus in process of time the differences producing trouble would have been gradually obliterated,” the report concluded. “Schools should be established, which (Indigenous) children should be required to attend; their barbarous dialect should be blotted out and the English language substituted.”

It took until 1990 for Congress to pass the Native American Languages Act to repudiate the erasure, bringing languages like Lushootseed back from the brink of extinction and encouraging Native languages to be taught in schools.

A 2012 study found access to both culture and language are essential in Indigenous child welfare. When Native youth reconnect with their ancestry and culture, they play an active role in breaking the cycle of generational trauma.

One study of First Nations in British Columbia suggested Native language retention — more than any other “cultural continuity factors” — had a strong correlation with stopping youth suicide. And when at least half of the Indigenous population retained conversational fluency in their Native language, the youth suicide rate dropped “effectively to zero.”

‘Almost broken’

Over a dozen paddlers disappeared into the gray horizon one morning last August.

The canoe journey is a reminder “we are still here,” said Sam Barr, a Samish tribal member and historical preservation officer for the Stillaguamish tribe.

“There’s over 10,000 years of archaeological evidence in Snohomish County of our people being here, and then we know that our stories go back even further than that,” he said. “We’re all about trying to restore that cultural chain of knowledge that … was almost broken.”

Descendants of signatories to the Treaty of Point Elliott began the “Paddle to Seattle” from Suquamish to Alki Beach in 1989, resurrecting a centuries-old tradition. The annual journey was created by Emmett Oliver, a Tulalip Indian School survivor born in South Bend in 1913. As supervisor of the state’s Native American student programs, Oliver worked to reform tribal education policy at the state and national levels. He’s also credited with ushering in “a new era of canoe carving and canoe travel upon the ancestral waters of the Salish Sea.”

“The fact is that Emmett saved hundreds if not thousands of lives,” Quinault Nation President Fawn Sharp eulogized, when Oliver died in 2016 in Edmonds at age 102. The resurgence of canoe culture “helped so many of our children and adults turn away from drugs and alcohol, and displaced depression and despair with hope and culture-based principles.”

The journey is a way to apply Indigenous knowledge and connect with the water.

“My father — his wish was to see 100 canoes in his lifetime land on Washington state land,” Oliver’s daughter Marilyn Bard said, “and that happened in 2013 with 103 canoes that landed in Olympia.”

Some paddlers, known as canoe pullers, sing in Lushootseed to urge each other forward. Their words echo far across the water.

Maria Rios, of the Tulalip Tribes, began lessons in the Central Salish language as a small child. There weren’t classes beyond Montessori at the time, said Rios, 31. But she hung onto a collection of class worksheets, translations and pictures — her “Lushootseed Bible.”

“And after school I kind of floated around until I decided I need to get a job,” she said. “Another lucky, destiny kind of thing: I started with a work experience program (at Tulalip) … learning the language and then going out and teaching things that I’ve been wanting to do since I was a child.”

Rios started teaching Lushootseed with Montessori students, including some of her relatives, in 2012. The class she and Nik-ko-te St. Onge began working with in 2014 just finished sixth grade at Totem Middle School — they’ve been teaching the class throughout their primary and secondary education.

Rios shares photos of Lushoostseed speakers like Martha Williams Lamont, an assistant minister of the Tulalip Shaker Church who died in 1973. Pictured from her knees up in a white dress decorated with shells, Williams Lamont shares a soft smile in the black-and-white photograph.

“I have some of her great-grandkids; great-great-great-grandkids in my class,” Rios said. “I’ll bring in her stories, and that offers that deeper connection for them.”

In 2019, Marysville School District and the Tulalip Lushootseed Language Department partnered to bring classes to Marysville Pilchuck High School. Natosha Gobin, a Lushootseed instructor in the district, helped to create a special keyboard to type the language.

“I mean, for me, it’s just that powerful reclamation,” Rios said. “You get to reclaim that, and it gets to be a part of you again.”

Six miles down the road from the former boarding school campus, a photo of Assistant Principal Chelsea Craig’s great-grandmother hangs in an office at Quil Ceda Elementary. Celum Young was taken to the Tulalip Indian School around age 5.

“They wanted me to forget my way of life and learn to be civilized and learn to be a good white person,” said Young, who died in 1987, according to research by Native American historian Carolyn Marr. “I still don’t know what a good white person is. All I know is that I learned to march, march, march, and not speak my language. You got in big trouble for that. I got many whippings and confinement.”

Ten years ago, Craig proposed a new way to start each day for 470 kids at the elementary school. They meet in the gym for drumming and singing, followed by whole school learning.

“Sometimes it’s Lushootseed stories or phrases or social-emotional learning — whatever it might be,” Craig said. “But every day, we start with singing a traditional song.”

Students lead the songs.

Native people rarely see themselves represented in mainstream curriculum. Craig is pushing Marysville schools to shift away from the white-centered narratives and toward seeing history through a broader lens. She doesn’t want Native students to feel invisible anymore — the way she felt in the same system. Indigenous people tend to be skeptical of government schools, in large part because of the boarding school legacy.

“And, frankly, a mismatch in education,” Craig said. “… We’re trying to reclaim colonized space.”

Starting fresh begins in the youngest learners. Many of them attended the tribes’ Early Learning Academy, near the site of the former boarding school. The Lushootseed Department offers weekly sessions for newborn to 3-year-old children. The academy’s goal is to help children converse in Lushootseed by kindergarten. Kids also learn about cultural traditions, like fishing and gathering native berries and roots.

The lasting damage of boarding schools is not just “a Tulalip thing,” Craig said.

“This is a United States of America thing,” she said. “All Indigenous people were required to go to the boarding schools. And their descendants are directly affected by those boarding schools, whether that’s consciously or not.”

‘When you know the truth’

Each time their relatives struck their drums to the beat of the Snohomish War Song, two dozen dancers’ feet touched the earth. Elementary school kids — some in orange, others in colorful regalia — bounced to the drumbeat outside the dining hall. It’s something their ancestors couldn’t do at that age.

Elders’ eyes traced the dancers as they moved.

Boarding school survivors and their descendants had gathered for Orange Shirt Day, in honor of lives lost and forever changed by the federal school. The annual memorial is named for a story told by Phyllis Webstad, of British Columbia, who showed up to a mission school on the Dog Creek reservation in 1973 wearing a shiny bright orange shirt her grandmother bought her. The school took the shirt from the 6-year-old girl and would not return it.

“I finally get it,” Webstad wrote, “that the feeling of worthlessness and insignificance, ingrained in me from my first day at the mission, affected the way I lived my life for many years.”

The Tulalip Tribes marked the day for the first time last October.

“These are historical traumas that keep on,” said Gobin, the tribal chairwoman, fighting back tears as she spoke to families. “I felt it in my dad, the pain he felt.”

On a table, candlelight illuminated sepia photos, like an altar, showing dozens of Indigenous children standing stiff and straight in itchy military uniforms.

“I think this is the first time I can, in my lifetime, remember coming together like this,” said Misty Napeahi, the Tulalip tribal vice chair. “We have to recognize that we survived this. We’re strong, resilient Indian people. And we’re that way because we’re a community.”

The federal government tried many strategies, for generations, to wipe Indigenous culture off the map. But it didn’t work, said Fryberg, the University of Michigan professor.

“When you know the truth,” she said, “you have to at least somewhat stand in awe because we have overcome so much and we are still here.”

After years of silence, the Interior report released in May finally began exposing wrongs committed against Indigenous people. But the United States has yet to offer a public apology for the harm. President Barack Obama signed an appropriations bill into law in December 2009, in which an apology was written, but never publicly acknowledged. But tribal leaders believe to have their treaty rights respected, they will need much more than a report and an apology.

“There’s not been the things that should be happening and respecting our sovereignty,” Gobin said. “Every day we have to fight … to uphold our sovereignty. You would think that we have our treaty rights and we have our sovereignty, so we should be moving on — but every day we have to fight for something that is guaranteed to us.”

Rep. Sharice Davids, D-Kansas, the second Indigenous woman ever elected to U.S. Congress, sponsored a bill to create a commission that could continue the research.

“If Native children were able to endure and survive the boarding school era in our nation,” Davids said in May, “we should be able to find it in ourselves to fully investigate what happened to our relatives.”

Congress provided $7 million for the Interior to continue the search for records, graves and stories.

Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Bryan Newland recommended the Interior commit to:

• producing a second investigative report;

• identifying boarding school survivors and documenting their stories;

• supporting the reclamation and co-management of federal boarding school sites;

• developing a repository of federal records pertaining to the federal boarding school system;

• identifying and engaging other federal agencies that may have control of relevant records;

• supporting congressional action to heal, through a federal memorial for generations of Indigenous children who lived or died in the boarding school system;

• and encouraging Native language revitalization.

At Tulalip, the opening prayers, songs and blessings of the long-outlawed Salmon Ceremony are conducted in Lushootseeed. Survivors of forced assimilation, Stan Jones Sr. and Harriette Shelton Dover, are often credited with restoring that tradition at Tulalip Bay.

“To me, it’s not revitalization,” Craig said. “It’s the sustainability of our people. In spite of the boarding school, we have always maintained who we were as Coast Salish people.”

This month, songs preserved by Tulalip school survivors echoed through the longhouse.

Isabella Breda: 425-339-3192; isabella.breda@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @BredaIsabella.

Read the rest of this series, Tulalip’s Stolen Children.

Part 1: ‘Genocide our people survived’: Tulalip school fueled generations of pain

Growing up in the Tulalip boarding school, Harriette Shelton Dover would “just sit absolutely still and watch my playmates die” of illness, hunger and cold. The Daily Herald dug into school rosters and other records at Tulalip, revealing a staggering death toll — and pain passed “from generation to generation.”

Part 2: Unearthing the ‘horrors’ of the Tulalip Indian School

The Tulalip boarding school evolved from a Catholic mission into a weapon for the government to eradicate Native culture. Interviews with survivors and primary documents give accounts of violent cultural suppression under the guise of education at the “Carlisle of the West,” modeled after the notorious Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Resources for boarding school survivors and their families

If you need to talk to someone now:

CARE Crisis Line: 425-258-4357 or 1-800-584-3578 (N. Puget Sound); Online Crisis Chat (24/7/365).

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

Crisis Prevention & Intervention Team: (Snohomish County) 425-349-7447

WA Warmline: 877-500-9276 or 866-427-4747.

Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Helpline: 1-800-662- HELP (4357)

National Sexual Assault Hotline: 1-800-656-HOPE (4673)

Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-SAFE (7233)

Find long-term support:

The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Directory.

The Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies Directory.

The Anxiety and Depression Association of America Directory.

Get connected:

National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.