MUKILTEO — A bronze plaque marking an 1855 treaty between local tribes and the U.S. government was stolen almost two years ago and replaced with graffiti that read: “BROKEN TREATIES.”

All that remained of the monument near the Rosehill Community Center was a slab of granite until last week, when a new plaque was installed to replicate the old Treaty of Point Elliott marker.

There is a dedication ceremony at 3 p.m. Friday, hosted by the city and Mukilteo Mayor Joe Marine. Tulalip Tribes Chair Teri Gobin will be there, along with traditional drummers.

For Marine, it’s a way to put back a piece of the city’s history. For tribal members, it’s a reminder of an ongoing fight to hold the government to promises made 167 years ago.

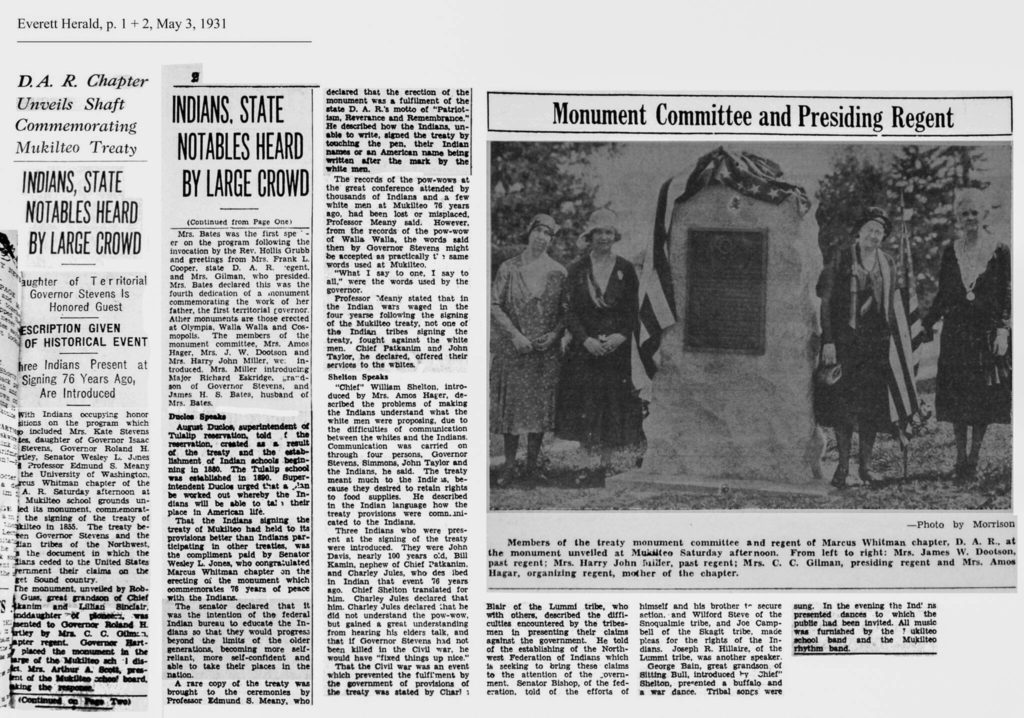

The monument at Third Street and Lincoln Avenue, which has a bench and landscaping, was erected in 1930 by the Marcus Whitman Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

In 1931, hundreds came to a ceremony where Robert Guss, great-grandson of Snoqualmie Chief Pat Kanim, helped unveil the monument. At the ceremony, Tulalip cultural leader William Shelton “described the problems of making the Indians understand what the white men were proposing,” according to an April 25, 1931 copy of The Daily Herald.

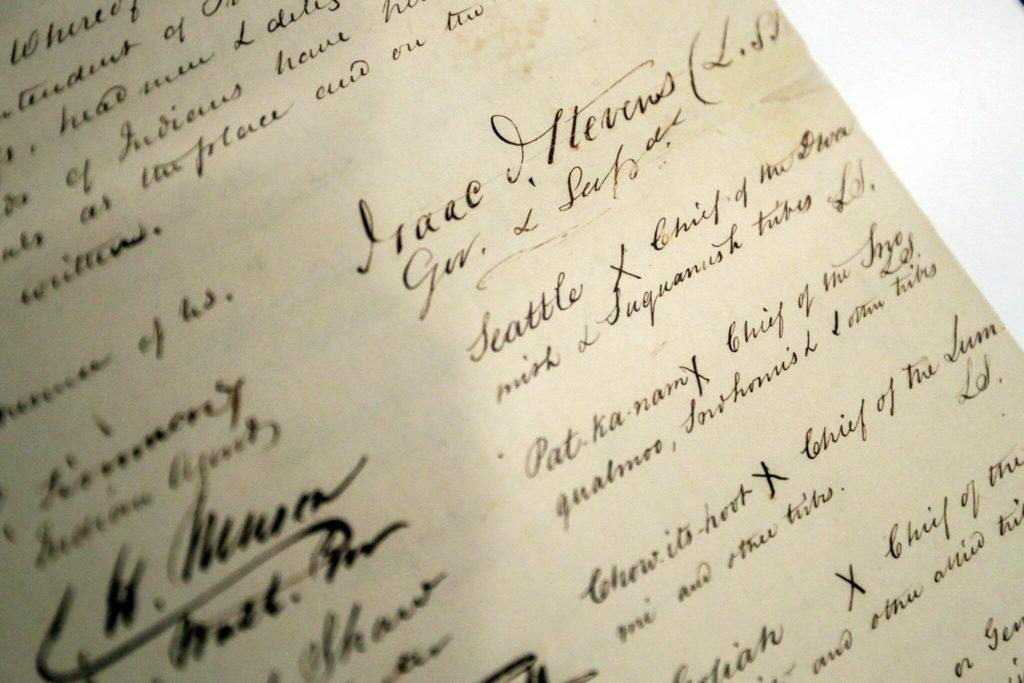

The plaque tells visitors that 82 Native American leaders “ceded the lands from Point Pully to the British Boundary.” In reality, leaders from today’s Tulalip, Stillaguamish, Lummi, Swinomish and other regional tribes marked nothing more than an “X” in place of their names.

Looking down at the line of “signatures” on the treaty under a glass case Tuesday evening at Hibulb Cultural Center, Tulalip elder and historian Les Parks paused.

“You can’t think they knew what they were signing,” he said.

In exchange, the treaty was supposed to maintain tribes’ “right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations.” It was supposed to secure tribal sovereignty and guarantee rights to traditional ways of life, education and health care.

Much of that, instead, was left up to interpretation. Today, tribal leaders often end up fighting for these treaty rights before government officials and in court, Gobin said.

In the late 1920s, Hariette Shelton Dover, a boarding school survivor and one of the first Tulalip board members, helped her father to advocate for treaty rights in a federal land claims case.

In the ’60s, longtime Tulalip Tribal Chair Stan Jones Sr. was in the middle of the landmark federal court battle that came to be known as the Boldt Decision — restoring treaty fishing rights.

In the ’70s, Terry Williams, a leader in Tulalips’ fisheries, natural resources and treaty rights offices, helped create the first co-management system in the state, in which tribal and non-tribal fishermen divide the salmon harvest each year.

In recent years, the tribes have fought to protect sacred sites in the Yakama nation and to restore fish passage in municipalities near and far, among many other things.

The Tulalip Tribes have a treaty rights office that meets regularly with other governments to ensure tribal treaty rights are acknowledged and the habitat and resources — upon which they depend — are sustained.

The replacement plaque has the same wording as the original.

“There was some talk of reaching out to the tribes and maybe changing the wording,” Marine said. “I read it. To me, it wasn’t disrespectful. I just wanted to get it replaced.”

Marine, who took office in January, said he consulted with one Tulalip tribal member, James Madison. Madison is a Coast Salish artist and master wood carver.

“My take was that we should never change the original plaque,” Marine said. “We should put that back exactly the way it was. Don’t change history. If for some reason we wanted an addendum or something to the side to update, that’s fine. … We can put something there that says the tribes disagreed with the treaty or whatever. I don’t think you do it on the plaque.”

Gobin said “it would’ve been nice” if the mayor had consulted with the tribes’ treaty rights office to “add more to the plaque that was more appropriate.”

For example, mentioning that the tribes were “forced” to cede the land, she said.

“It’s important that people in Mukilteo know: the lands they are on are our traditional lands,” Gobin said.

Jennifer Gregerson, the previous mayor of Mukilteo, didn’t plan to replicate the plaque. She received input from a couple of tribes to draft a proposal with revised wording and an explanation.

“I was regretful that I didn’t have time to get that done before I left,” she said. “It’s too bad the city didn’t pursue that path. It was a great opportunity to rethink our history and honor our more nuanced understanding today of those events.”

To Parks, the treaty is a reminder of what was lost.

“To me, it’s a day of mourning,” Parks said. “January 22, 1855. We should be mourning and not celebrating.”

Archaeological studies revealed the Sduhubš, or Snohomish, people maintained a village on the shore of what’s now Mukilteo for at least 4,000 years, said Ryan Miller, director of government affairs and treaty rights for the Tulalip Tribes.

Mukilteo, known in Lushootseed as bəqɬtiyuʔ, was historically seen as a central meeting place for tribes who used the waterways as highways on canoe.

Descendants of the signatories to the 1855 treaty now live on small reservations spattered across the region: Tulalip, Swinomish, Lummi, Upper Skagit, Muckleshoot, among others.

“We were hoodwinked into signing the treaty,” Parks said, “and had we not signed it, we would have probably been eradicated anyway.”

Marine looks at it from a different vantage.

“That plaque was put there in 1930 and was very much part of our history and needs to go back,” the mayor said. “It was stolen and we need to put it back the way it was.”

Marine took it upon himself to replace the plaque. He said advice or approval from the City Council was not required.

The replacement plaque was ordered from an out-of-state company because the price, $1,819, was considerably less than estimates from local vendors contacted, Marine said. The funds came from the mayor’s office budget. The plaque weighs about 75 pounds.

The stolen plaque was never recovered. There are plans to put a camera on a nearby lamppost.

The ceremony coincides with the opening day of the three-day Mukilteo’s Lighthouse Festival. The city is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year.

Isabella Breda: 425-339-3192; isabella.breda@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @BredaIsabella.

Andrea Brown: 425-339-3443; abrown@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @reporterbrown.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.