EVERETT — Authorities are clearing a downtown homeless camp amid safety concerns, leaving the dozens of people living in tents and under tarps few options for where to go next.

Notices posted Wednesday at the Snohomish County-owned plaza on the northeast corner of Oakes Avenue and Wall Street warned that the campus would be closed to camping on Sunday at 5 p.m. Anyone remaining may be arrested for trespassing, said the signs, plastered to a chain link fence that partially surrounds the encampment.

County Executive Dave Somers made the decision to break up the encampment after the sheriff’s office was called to the area for several incidents in recent weeks.

More people will soon be coming to the campus for jury trials at the neighboring county courthouse, Somers said.

“It just was not sustainable. We knew it was temporary anyway,” he said. “It’s just not a safe situation.”

The decision follows a reported assault and a robbery near the camp that have spawned security concerns among county leaders.

At about 12:15 p.m. on June 19, a female county employee reported that a woman had struck her in her arms and chest near the entrance to the courthouse, according to the sheriff’s office. The suspect, a 41-year-old Everett woman, later admitted that she swung at the employee and was arrested on suspicion of fourth-degree assault, said sheriff’s spokeswoman Courtney O’Keefe.

The employee worked for county Clerk Heidi Percy, Percy told The Daily Herald on Wednesday, before the notices were posted at the encampment.

“It’s a sticky situation,” Percy said. “I can certainly sympathize with the situation that the homeless are facing, but I’m also concerned about the safety of our staff.”

On Saturday, a man reported that he was punched in the face and robbed at the camp the previous afternoon, O’Keefe said. The culprit stole the man’s phone, money and lottery tickets, the victim told authorities.

“It would appear to me that this really isn’t a good situation for the people in the encampment, and it’s certainly not a good situation for our county employees,” Prosecutor Adam Cornell said Wednesday.

The dispersal comes at a time when the coronavirus crisis has limited the operations of local shelters and many of the area organizations that typically serve people who are homeless.

It also goes against the guidelines of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which recommends that authorities allow people who are living in encampments to stay there unless other housing options are available.

“Clearing encampments can cause people to disperse throughout the community and break connections with service providers. This increases the potential for infectious disease spread,” the CDC’s website says.

Somers said he was not aware of that particular CDC guidance and noted the encampment provides little space for people to socially distance.

“We’re working with the city to try and find a longer-term situation. We don’t have anything yet,” Somers said. “We’ve been trying to be tolerant and working with folks as best as we can.”

Employees of the county Human Services Department have offered to connect the people living in the camp to housing and other resources. Some have refused services, county officials say.

Penelope Protheroe, who runs a nonprofit that provides assistance to people who are homeless, visited the encampment on Thursday to check in with folks there.

More than two dozen tents remained on the concrete patch, dotted with shopping carts and bicycles. Portable toilets line one side. There were even a few potted flowers.

It’s the closest thing Everett has ever seen to a sanctioned encampment, said Protheroe, president and CEO of Angel Resource Connection.

“Where are you going to go? What do you think you’re going to do?” she asked Alissa Sales, who’s been living in the encampment.

“I don’t know,” said Sales. “I don’t know.”

Sales, 45, said she has already signed up for housing assistance.

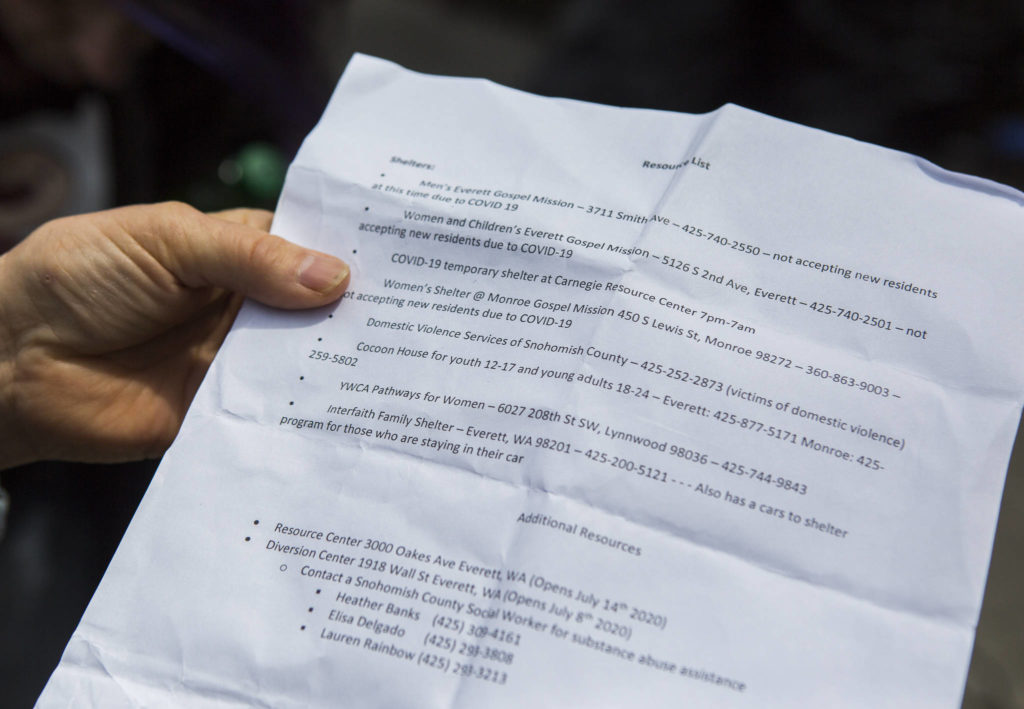

Sheriff’s deputies who visited the encampment on Wednesday gave her a list of resources. But three of the eight shelters listed aren’t accepting new residents due to COVID-19, the flier notes. Another, the temporary shelter at the nearby Carnegie Resource Center, has long been full, those at the encampment say. Others listed cater to specific populations, such as survivors of domestic violence or families with young children.

Many people with mental illness live in the camp and need treatment. Government leaders “aren’t addressing the issue at all,” Sales said. But the problem adds to the stigma that she and others face on a daily basis.

“I know that they’re not going to go for us being downtown because the community can see us,” she told Protheroe as the two brainstormed places where she might be able to sleep in coming days. One option floated was a Denny’s parking lot.

Between January 2019 and January 2020, the number of homeless people in the county increased by about 15 to roughly 1,130, according to figures released this week from the annual Point-In-Time Count.

Officials anticipated a more significant jump, considering that in the year prior to the count there was a more than 10% increase in the number of people seeking and receiving housing services through “the county-wide homeless response system,” according to a news release.

Homelessness is up nearly 40% since 2015; the number of people living in shelters has more than doubled from 312 to 673 during that time, the survey results show.

The number of homeless veterans and families with children has fallen since last year, the data show.

Of the family count, families of color made up a disproportionate 38.7% in 2020, according to the survey.

Chronic homelessness has also risen and now accounts for more than half of all people who are homeless in Snohomish County, the results show. The term refers to individuals who have experienced long periods of homelessness and a disabling condition, such as a mental or physical illness or substance use disorder.

The most recent survey doesn’t capture the impacts of the coronavirus crisis, though. The pandemic is expected to lead to a wave of new people experiencing homelessness once supplemental federal aid programs and Washington’s eviction moratorium ends.

“There is a concern that we might have more people with serious needs,” said county Human Services Director Mary Jane Brell Vujovic. “We’re doing our best to prevent that from happening. There are factors that make that a challenge.”

Months, sometimes years, can lapse before someone who has applied for local housing programs can get a unit, said Protheroe.

She visits the encampment a few days a week to hand out meals and help people get connected to resources.

“We know that most people here want to get into housing,” she said. “The bias out there is that hardly anybody wants it.”

Pedro Espinoza, 49, said he’s been waiting for housing for more than six years. He has “no idea” where to go and plans to stay at the encampment until he is asked to leave.

“And then move onto wherever I can after that. Fingers crossed and see what happens next,” he said. “It’s just another day, unfortunately.”

Rachel Riley: 425-339-3465; rriley@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @rachel_m_riley.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.