SULTAN — Jim Tinney lifted up his building to repair damage from Sultan’s persistent flooding.

Tinney, owner of Kiss the Sky Books, bought the building at 401 Main St. eight years ago. Prior to occupancy, he had a company rebuild the foundation, raising the floor.

Damage from over a century of floods had destroyed the wood pilings that originally kept the building, built in 1892, in place.

“It was put up on a foundation of logs sunk into mud,” Tinney said Friday. “And they had completely rotted away. There was nothing holding the building up except for its own structure.”

Now, treated wood posts, sunk into concrete pilings, anchor it. In the years he has owned the building, he has seen water come within 30 feet of his business. The building is about 2 or 3 feet above street level, Tinney estimated. It would take a true disaster for water to reach his front door, he said.

Each fall as the weather turns, county authorities look to get the public prepared for rising water. Over 75,000 local residents live in flood-prone areas, according to the Snohomish County Department of Emergency Management.

Tinney and pretty much everyone else in downtown Sultan is serious about flooding. It’s a threat every year — and the best long-term forecast suggests it’ll only get worse in the coming decades.

A 2021 study by the Climate Impacts Group found the Snohomish and Stillaguamish river basins could see peak flows increase up to 40% by the 2080s. The Skykomish River floods often, especially from Gold Bar to Monroe, where the river twists into the Snoqualmie and gets rebranded as the Snohomish. When a heavy rain hits in Sultan, at the confluence of the the city’s namesake river and the Skykomish, muddy water can make a lake out of Sportsmans Park, River Park and downtown.

‘At least one flood’

Sultan’s City Hall is just a few steps away from Tinney’s store.

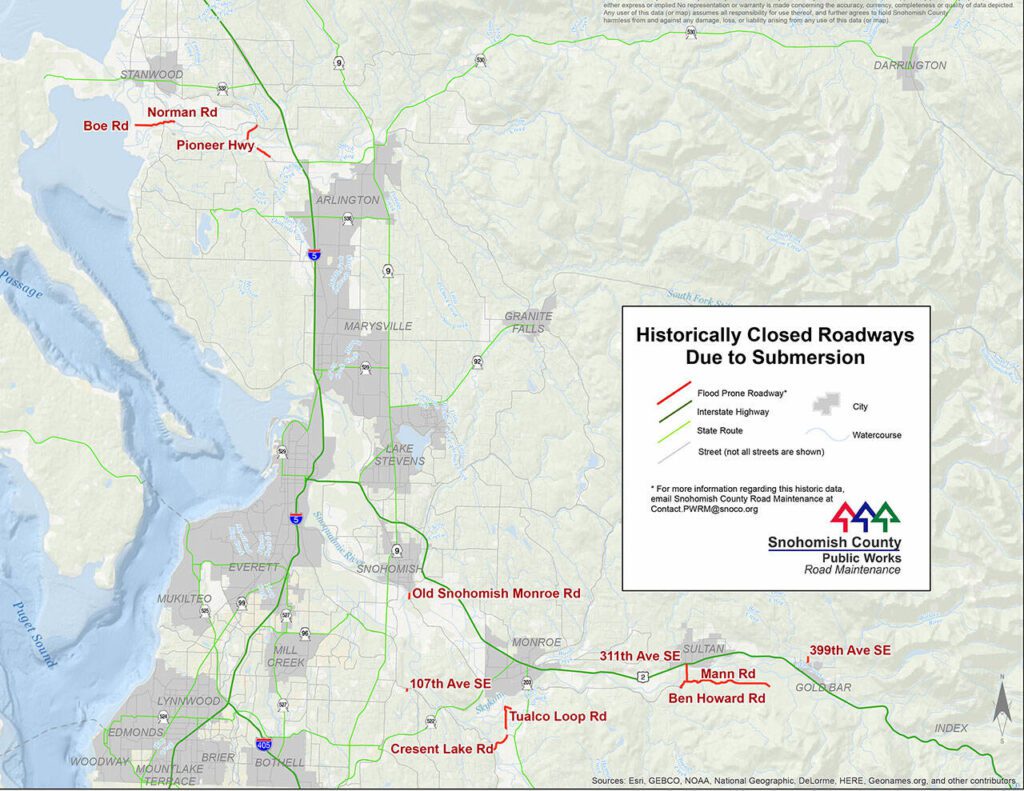

Snohomish County recently poured over $5 million into raising roads in the area, including Mann Road and Ben Howard Road south of the town. Ben Howard is one of few routes connecting Sultan to western Snohomish County.

“It will be interesting to see if the work they did this summer has the intended effect,” Sultan Mayor Russell Wiita wrote in an email to The Daily Herald.

Sultan built a facility to house sandbagging operations four years ago, paid for in part by state money. A conveyor belt deposits sand into a bag, which a worker then takes to a sewing station where it’s fastened shut. Sandbags go on rotating pallets, wrapped in plastic and stored.

“It is common for at least one flood each year to cause the Sultan River to backup into downtown causing us to close 1st Street near Main St,” they mayor wrote. “Outside of City Limits, surrounding farms fields can be flooded and residents on Mann Road can be stranded due to water over the roadway.”

When a flood’s coming, the sandbag pallets are positioned throughout Sultan.

“This process has allowed us to prepare multiple pallets of sandbags ahead of time so that they are ready to deploy at a moments notice,” the mayor wrote in an email. “Prior to this setup, volunteers would come out to our public works yard, fill sandbags and tie them shut by hand. The sandbags would then be thrown onto trucks and deployed to affected areas.”

The new setup is more efficient, he said — from personal experience as a volunteer.

“It was often hard to keep up with the demand,” Wiita wrote.

Tinney said he was a big supporter of the sandbagging.

“That’s really just a fantastic investment they’ve made,” Tinney said.

‘Used to be fairly predictable’

Kevin Walker, owner of Loggers Bar and Grill in downtown Sultan, bought the establishment in October 2022. He has yet to live through a bad flood season here as a business owner. But he’s well aware of what he could be up against.

“In years past, it’s put 2 feet of water in the bar,” Walker said Friday. “At that point you shut it all down. I plug all the sewer drains because that’s where most of your water comes from.”

Wiita and his staff monitor river gauges during the rainy season.

“It used to be fairly predictable that when the Skykomish reached a certain level in Gold Bar, we could anticipate water in downtown Sultan. The past couple of years have changed that a bit,” he wrote. “When we have expected to see the river backup into downtown based on the gauges, it hasn’t materialized to the level it did before.”

He suspects that has something to do with the Sky’s ever-changing path, suggesting the river has carved out more flood storage space upstream.

Shingelbolt Slough is a project Wiita has supported, to add more floodwater storage. Construction is expected to begin by 2025 on the 35-acre project.

This year, the Snohomish County Department of Conservation and Natural Resources received $10 million in state money for floodplain work near Sultan and Monroe. Marysville and Stanwood also received $2 million for flood risk reduction projects earlier this year. Part of that money will go to repairing dikes and levees.

Snohomish County is also planning to restore Chinook Marsh near Ebey Island, which could provide flood protection in addition to habitat restoration.

“There’s that old adage that water always wears away the rock over time and that is absolutely what rivers are trying to do, right?” said Lucia Schmit, Snohomish County emergency management director, earlier in November. “They’re trying to gain sinuosity over time, and so the best thing we can do to protect human property and to provide a health environment is to give the river room to do that.”

‘Give the river room’

Snohomish County is a place where snowcapped peaks feed into the sea through a maze of waterways — and newsflash, it rains here, too. In the darkest three months of the year, the foothills around Monroe average about 20 inches of precipitation.

Since 1962, Snohomish County has had 18 floods large enough to rise to the level of a presidential disaster declaration. A flood in December 1975 created a 50,000 acre “lake” between Everett and Monroe. Floodwaters tore a 300-foot hole in the French Slough Dike, destroying over 300 homes.

Climate change is projected to increase flooding and cause more intense rainstorms. Rising seas could make coastal areas flood more often. Warmer temperatures mean the precipitation falls more often as rain, less often as snow.

Storms that included flooding have accounted for around $190 million in damage to unincorporated Snohomish County since 1990, according to county data.

According to data complied by the National Flood Insurance Program, claims reached $28 million last year around Washington. It was the most of any state in 2022 and came after destructive storms in January 2022. Huge swaths of southwestern Washington were underwater and I-90 closed at Snoqualmie Pass after nearly 40 avalanches buried the roadway.

It remains to be seen exactly how a massive burn scar from the 14,000-acre Bolt Creek wildfire will affect the watershed long-term. State crews were working on a $1.2 million project this fall to build debris flow fences along U.S. 2 northwest of the city of Skykomish, to shield the highway.

‘Until the water recedes’

Flooding is a thing that happens here, Schmit said.

“It is not an anomaly, it is a seasonal occurrence,” she said. “And there are steps people can do to minimize the impact.”

For one thing, reporting clogged storm drains can help.

Clogged drains can cause urban flash flooding, sometimes in conjunction with a major windstorm.

“Every drainage system has a maximum capacity to transport water, and heavy flooding may overwhelm some systems,” wrote Doug McCormick, public works deputy director and county engineer, in an email. “There is little that can be done under those circumstances other than to avoid flooded areas until the water recedes. Still, it is important to unclog drains as quickly as possible.”

County crews will close roads “if the conditions of the road become hazardous for travel due to the depth or velocity of water overtopping the roadway,” McCormick wrote.

Public works uses data from previous floods for flood projections.

“We are able to predetermine the likely depth and volume of water that will occur over some roads based on predictions about the flood levels from weather services and the Snohomish County Real-Time Flood Information System,” McCormick wrote. “We use this information to help us determine where and when to put protections in place before the danger occurs.”

Snohomish County has a real-time map of road closures on its website. And launched its improved hazard viewer tool this fall.

Emergency management uses the same Ready-Set-Go evacuation levels as they do with wildfires and other disasters, Schmit said.

Six inches of water can knock an adult off their feet and 12 inches can wash away a small car. Floodwater depths can be hard to predict with the naked eye.

“You don’t really know how deep the water is until it’s oftentimes too late,” Schmit said. “What it comes down to, is if you see the water, turn around.”

Calls for water rescues can also stress first responders who are already busy, “whether it’s helping with flood response (or) doing the rescues,” she said.

So it’s important to reduce the number of “extraneous rescues,” Schmit said.

“We don’t want to put them in any more danger than they need to be,” she said.

Preparing for floods

• Store food and sealed water in a dry place.

• Have a first-aid kit.

• Stock up on batteries and have several light sources.

• Consider getting a battery-powered or solar radio.

Jordan Hansen: 425-339-3046; jordan.hansen@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @jordyhansen.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.